If you want to learn what a culture values, eat within that culture. Eat at a home. Eat. Eat. Eat eat eat.

Ever since I moved in with my host family (8 days ago), I sit at the dining table for three meals a day everyday. I can’t remember the last time I did that- high school? When it’s up to me, I live for snacks. Why eat dinner when cheese and wheat thins and hummus are an option and I don’t have to do any dishes?

But here in Guatemala, I sit for three formal meals a day. Three prayers. Three Buen Provechos. My host mom sits with me for each meal.

During training, Peace Corps pays the family to cover our meals. They give me an envelope and I give it to her. Once training ends, I will be on my own again. I like the schedule of eating three meals a day but I imagine I will fall back into peanut butter habits when I am responsible for myself. It’s possible that my new host family won’t stand for that.

Home meals here are so different. The family life here is grounded by the tradition of sharing a meal. The woman of the house is responsible for preparing the meal, for her husband, her sons, everyone.

It’s true, I’ve learned so much about the way this family operates simply from the experience of a meal with them.

I wonder if it’s possible to theorize about entire family dynamics by observing how they eat dinner. Where is the distribution of power in a home and how does it relate to the dinner plate?

One of my ‘brothers’ is engaged, but I’ve noticed his fiancé does not usually help in the kitchen. She doesn’t offer to do the dishes afterwards, either. I’m not sure if this is out of respect for my host mom i.e. this is her territory, but to me it is unusual. But her sons never offer to help with the dishes. They may help clear the table, or set it, but usually they simply sit when a meal is ready. I’ve never seen them prepare food for themselves.

Setting the Table:

For every meal, my host mom Rosa Maria lays a beautiful fabric on the table with placemats, an overturned glass, a napkin with a fork, knife and spoon (depending). She prepares the plates in the kitchen, then carries them in with the help of her officio domestico Andrea (and I offer to help transport the plates when I am in the kitchen too).

In some homes it can be an imposition to offer help since you are the guest. This is especially the case if you are a man. Guatemalan women see it as their role so serve men. You may be subtly implying that they aren’t doing a good enough job serving you. But Rosia Maria and I have an understanding. She even lets me do the dishes every night after dinner. She offers to help but usually I like to do it.

As gender roles go, the woman is concerned most with serving the men.

If my host mom forgets to put ice in her son’s glass or to set the table with a knife, she says “Con permiso mi hijo.” I just can’t imagine an American mother saying to her son “Excuse me my son, I forgot the ice in your juice.” I’m sure it happens, but it’s not the norm.

The Prayer:

When we first ate, she did not pray. After that first meal, she asked me “is it okay if I pray for our food?” and I said “sí!” Her prayers are like a fun game for me because we say two “Amens” before the final “Amen.” I know that after the first two pauses, I insert my Amen quick like a bunny so that my Amen is not late. She pauses briefly where the amens are supposed to go. After bendiga, and after cielos, I say “ah-men” with everyone else at the table. I don’t know the rest of the sentences, but I know bendiga, and I know cielos. But I can’t get tricked because she pauses a third time and no amen goes there, just air.

She says the prayer so fast that I still don’t know all that she is saying. You know how prayers use older words that people don’t necessarily use in the normal course of things. I know she says something about “May God bless us and thank you for everything you’ve sent from the heavens.” I also noticed that when my stomach was giving me trouble, she modified the prayer to make a request for my good health. I can’t think of anything sweeter.

I don’t like prayer very much at all when it is in the context of the American Christian church. It feels like listening to a language I know but don’t understand. When my host mom prays, it is like listening to a beautiful language that I understand but don’t know. Her religion has never asked anything of me, and the religion of my parents ultimately asked more of me than I wanted to give. So I prefer the unfamiliar, foreign prayer: it can be whatever it seems to be to be. Plus the amen game.

The Thank You:

After the prayer, you say “Buen Provecho!” After you finish eating, you sit and chat and stare at the music videos (when they’re on) or movies if that’s what they are watching. After you sit for a while, with some pauses, eventually you make a move to leave the table. As you do that, you say “Buen Provecho!” again. You have to time your departure. You can’t get up the second you are done. That’s not how this works.

The way my host mom says it is with a very particular emphasis. Buen Provecho, almost like an emphatic, sincere robot. It’s routine. It’s what you say. You can also say “Muchas Gracias” in either case, instead of Buen Provecho. I like Buen Provecho.

Once, Francisco finished his breakfast as I was sitting at the table typing on my computer (I’d eaten already). As he got up, he said “Muchas Gracias.” I said “Sí.” But I should have said “Buen Provecho!” I didn’t understand why he was thanking me? I did not make his breakfast. I did not even talk to him while he ate it. I think it’s like saying “I’m excusing myself now.” But it was my first day, I didn’t yet know about the amens!

During the Meal:

No napkins in laps. I asked once but they don’t do it. They just leave it by their plate when they need to wipe their mouths. I think the way I asked was: I put my napkin in my lap and looked at Rosa Maria for confirmation. Instead, she smiled acceptingly but not affirmingly. So I stopped putting my napkin in my lap.

It’s normal to place paper towels or beautiful tea towels over any open baskets or drinks or plates. You even place them over open containers of juice because the flies flock. That’s a new one for me.

Since we are inside when we eat here at Rosa Maria’s, we don’t put towels over everything like that. At Doña Fabiana’s house, there are towels over everything because their dining room is under a terrace, outside. Amanda’s bedroom is indoors but the living areas are outside. Even the tv sits outside in the comedor area.

The Actual Food!

So far, there’s been quite a variety of food served. I thought it was just going to be beans and tortillas every day, every day, every day. Tortillas accompany each meal (not breakfast). Pan/bread accompanies breakfast. Coffee is always ready at breakfast. Sadly, I have had to embrace drinking dark coffee. I miss liquid cream so much it hurts.

Rosa Maria makes her salsas fresh. She serves boiled potatoes cold (I don’t know how it works but it’s still tasty) with interesting varieties of boiled vegetables. Usually there is melon and/or papaya with breakfast and lunch. Warm soups. Tamales with chicken meat inside, sometimes sausage or lunch meat chopped up with sauces on top.

And yes, there are beans. Lots of beans.

Dessert:

We don’t have it. Not after breakfast, lunch or dinner. It makes me sad. But also it’s better. But also it’s sad. Also there is no such thing as American cake here.

Alcohol:

I haven’t touched a beverage since I arrived in Guatemala. I drank my last beer in the hotel in Houston, a Dogfish Head.

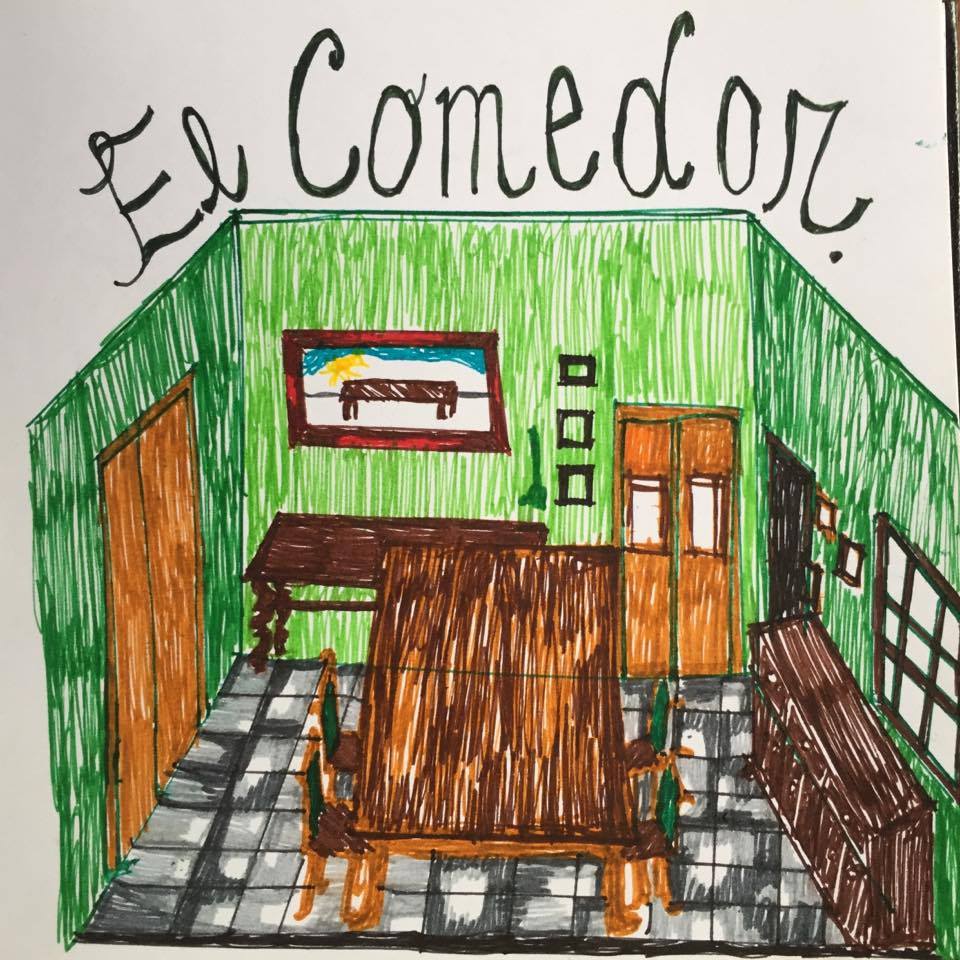

There are beers and tequila lined up neatly along the side table in the comedor, but I haven’t seen anyone touch a drink here. When I was at the wedding shower party, there was juice but also no alcohol (it was in the middle of the day, so there’s that..) We are not to drink during training. There are evangelical families here and for us to drink here could stigmatize us in the community. It’s important to be super-discretionary, and it’s best to abstain completely during training. I’m grateful that the option is off the table.

The Dishes:

After dinner, I take los trastos to la pila. La pila is an L-shaped thrice-segmented sink with a faucet over the center ‘bin.’ Clothes and dishes get washed in la pila. To the left, there is a blue container that you use to scoop water from the middle. To the right, a yellow container. On the left is where the dishes get washed. There is a small plastic container of a liquid/solid soap called “Axion” and two thin sponges that rests on the soap. Once you clean the dishes with the sponges, you scoop water out of the center bin and pour it over the clean dishes. Once the soap se fue, you set the dishes on the rack above the left side. Theoretically, the sink is drained once a week and cleaned out with bleach. I’m sure Andrea (the helper) does this because Rosa Maria runs a tight ship. I can’t say that the cleaning of the pila happens in all the other host homes.

And that is how I have been eating since my arrival to Guatemala!

We had dinner with you folks tonight at Cracker Barrel. It was fun. Glad you like your meals and living situation. It sounds good.