I’m a new woman!

Actually, I’m exactly the same. But I’ve had a Mayan makeover (I couldn’t resist the alliteration).

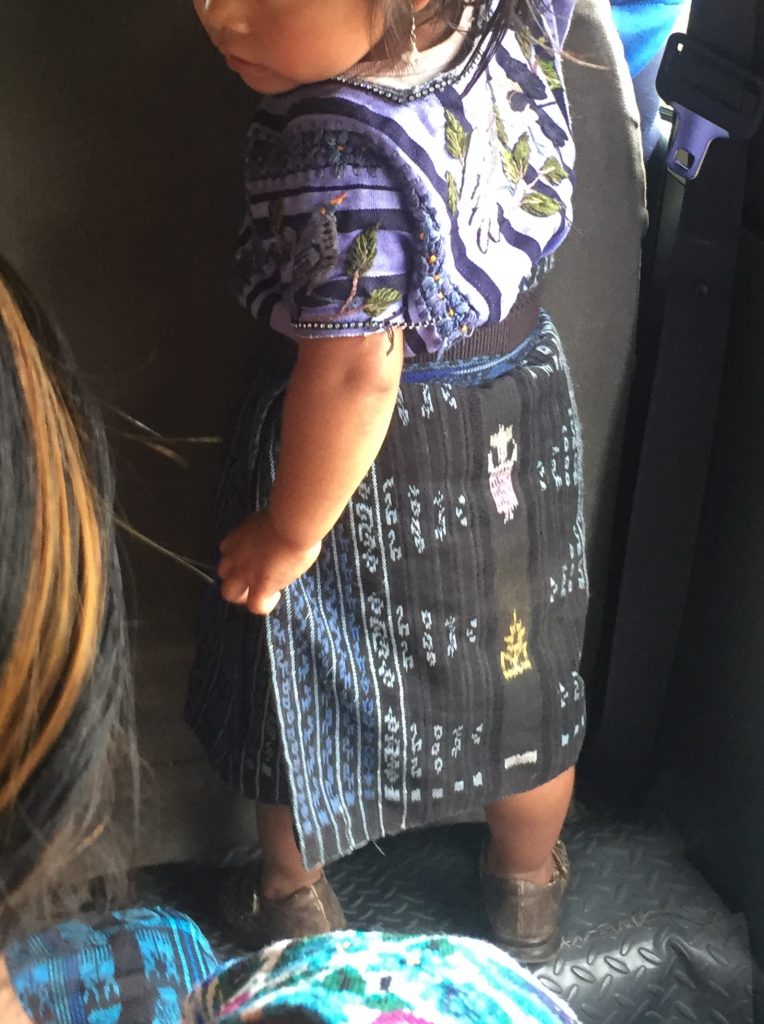

I finally acquired a complete set of traje típico: güipil, corte and faja. A Güipil is a woven blouse, erupting in textured colors, patterns and shapes. Admiring a güipil is a lot like gazing into a woven painting, and they’re everywhere you turn in Santa Clara (and most of the rural Western Highlands of Guatemala). The women wear them like Estadounidenses wear cotton. A Corte is a woven piece of fabric worn as a skirt. You buy corte by the yard/barra (mine is 4 barras) but most buy 6 yards and then tailor it to their size. I say this because my skirt is just barely enough and folks say: How many yards? when they see me. You know, chit-chat. And the piece that literally holds it together is the faja, the woven belt that is stretched around the skirt, pulled tightly and tucked in. There are three pieces to the ensemble.

A surprising fact: they are expensive! For me to buy them on the US dollar is even pricey, and that is expensive if you consider the exchange rate (1 USD is worth 7Q). A güipil (blouse) ranges between Q90 (the very cheapest) and Q600. To give you a sense here, my monthly rent is Q1000 for a 2-bedroom apartment, separate bathroom and pila (sink). So Q600 for a blouse is more than half of my monthly rent. So in USD a güipil can cost up to $83 USD. It’s spendy.

But I’m not complaining, just the opposite. I’m expressing the value that these items have. Families here will spend for their daughters to be in expensive woven blouses they will surely outgrow. But it is a tradition and a matter of preserving their heritage. And it’s expensive because ‘cuesta la hecha, Natalia…’ my host mom says as she weaves. They require patience, precision and experience to make.

The fourth piece of corte is a delantal/apron. I do not wear it with my corte because wearing an apron outside of the kitchen makes me feel weird. Delantales are meant to match with your corte. And most women wear them as accessories, use them as their wallets (they have pockets), and a whole host of other purposes. Even young girls wear aprons when they are dressing up. I’ll talk more about the significance of the delantal in another post.

The corte and faja feel unusual at first but somehow natural, like my soul was meant to don traje típico. It’s like my body has kept this secret all my 30 years that it’s meant to be wearing woven fabrics and dancing through my site whenever I hear music and the motion takes me over. I will tell you: the faja feels a lot like a modern day corset. It’s a looooong piece of fabric wrapped several times around and ratcheted to the tightness you want. My host mom asked “Is there a line around your waste when you take it off?” And I say: “Ummm. No?” and she says “Well there’s a line left on my skin when I take it off.” The fajas range in widths, too. They can be very thin (my host mom prefers this) and my host sister Clara prefers medium-width. I like the thinner ones cuz they don’t push on my rubs. I tell my sister when she wraps it around me that I want it to be loose. I think they’re a little nervous it will fall off of me, and I’m a little nervous I won’t be able to breath.

When I first got to site my eyes had to readjust to traje típico. During training, I noticed if women were wearing traje (because they stood out). Now in site, I notice if women are wearing pants because they are the ones who stand out. My host sister (age 38) wears pants but only when she sleeps. She says she has pants which she wears in the capital, but she doesn’t wear them here in Santa Clara. My host mom (age 64) never wears pants. Has she ever worn pants? I’ll have to ask. She changes her blouse to a t-shirt for sleep but she leaves the corte on and loosens the faja (belt). I’m sure Abuelita (age 90) has never worn pants in her life. I’m sure of it. If I saw Abuelita in sweat pants I think I would faint. If I saw my host mom in jeans I would not recognize her. In fact, I have never seen the outline of her legs.

At first blush traje does kind of look like a woven sheet tied around their middles. I still have to get help from Clara to put it on me. I have to hold the corte up like a barrel around my legs. She circles around me and forms two pleats at either of my hips. If she doesn’t, the skirt is restrictive and you can’t move your legs to walk. Then she pulls the faja (belt) tight around me as I hold the skirt in place. The blouse has already been tucked into the skirt and belt before it’s tightened. Then the edges of the belt are wedged inside the tightened layers and I’m good to go.

When I wear traje, the expressions on the faces change. I am always noticed in site no matter if I am wearing a unitard or a plastic bag. There is no question. Children pause and stare in the midst of play as I pass their houses, daily. Sometimes they yell “Shhht. La Gringa!” to direct attention to the passing weirdo, like I’m on foreign parade.

But when I wear traje, I am regarded as different and the same. In traje típico, I am a unusual flavor of cake layered in a familiar flavor of icing. I don’t ‘fit in,’ I stand out possibly even more when I try to fit in (in traje).

But the responses are not negative, they are so unexpectedly gorgeous: the people see me in traje típico and it’s as if I’ve been told The Secret Password. And we all believe the same thing for the first time. And we all acknowledge it and we are all on the same planet rotating in separate orbit from the rest of the world. The reactions bubble up from their souls as their smiles spread wide. And they ask me “how much?” They always ask “how much?” “Where’d you get it?” “From Who?” “En Serio??”

And when I wear traje and I speak K’iche’, I might as well be handing them a cone of ice cream they are so delighted. OK the reaction isn’t that strong because free ice cream is like Christmas, but the feeling is nearly there. “Xeq’ij Nan” I say as I pass Señoras on the street. We are both in corte, faja and güipil and we are greeting each other in ‘la lengua materna.’ It’s a beautiful exchange.

I must admit, I do not know the history of the Mayan traje like I should. But I don’t have to know the history to see how the significance runs beautifully deep. The K’iche’ culture has fought to defend it. The beauty of their culture is preserved in the dignity of traje típico (as with so many other customs).

The beauty in this, besides the fact that I am the proud owner of beautiful clothes I would not be exposed to had I not lived here, it’s that I am invited to wear these clothes. Yes, I know that I do not share Mayan roots and that my identity does not change when I wear traje. But my intention is to nod to the tradition and beauty of the Mayan culture when I am wrapped in this fabric.

The easiest way to set yourself apart from tourists is to wear traje WITH the skirt, not just the blouse with your jeans.

Now when I wear pants the day after I wear traje I hear: “And your corte?” And I don’t have a good response! All I can say is “No, not today. But I will soon!” The fact is that pants are more comfortable to me. It’s what I know. But I don’t identify with pants like they identify with traje. I know my pants are probably woven in Indonesia but traje is never, I repeat NEVER, imported from somewhere else. It would defeat the purpose entirely. Yes, many buy the thread from Alemania/Germany, but they are always made by Guatemalan hands.

And when I put on these beautiful clothes, my host mom looks at me and says “Look at the mujerrrrr.” I have transformed in her eyes. In traje típico I am womanly, I am beautiful, I am a part of this pueblo (albeit a long-term visitor). But I have knocked on the door and they have opened it to me. And that is how it feels to wear traje. I am an invited guest at the table of rich cultural heritage. And the Mayans have fought and fought to preserve their heritage. As I read Rigoberta Menchú’s book and she mentions her güipil, I can feel the textures in my mind. I can look over at my hanging güipiles on display in my makeshift closet.

Another dazzling feature of traje is that the patterns and colors are unique to each pueblo. Like a strong accent from Statesboro, Georgia, a lilt is a dead giveaway of a Southerner. Here the dialects are also identifying features (K’iche’ vs. Tz’utujil vs. Mam- there are 22 in all) but the traje típico greets you before you hear a word. “Those colors are from San Juan La Laguna.” “Oh that guipil is from Huehuetenango, I think that corte is from Aguacatan?” “How much?” The origin becomes a guessing game and a point of conversation. Santa Clara has their own típico but it is very simple (and I am quite honestly not a fan so I opt to buy other patterns).

And speaking of the dialects, when I make a phone call on the microbus and I say “Xeq’ij Hermana. La utz a wach?”/”Good Afternoon Sister, How are you?” I feel the ears on the bus perk up and the laughter ripple. I am not just an outsider passing through, I am spending time in the campos and the smaller communities of this country and I am learning how to greet in K’iche’ and to wear the fabric of my pueblo.

My host mom once described someone as ‘puro corte,’ purely skirt directly translated. She is saying: “That person is Mayan, not ladino. That person is one of us.” That phrase caught my attention. But when I put on traje and come downstairs, they gasp and my host grandmother giggles in delight. My Host Mom: “Mira la mujerooooon.” I am womanly in the corte. The first time she’s ever called me womanly was in traje.

Maltiox, Guatemala. Maltiox (Thank You). Thank you for having me and for accepting me as I wear traje and learn K’iche’. It feels so lovely to be invited in.