Check-out the first part first!

It is past dark and the program begins.

I must say, Seño Graciela looks beautiful. She is wearing the traje típico of Santa Clara, the classic pattern with a simple dark blue background with a bright, pink line down the center.

After Seño Graciela and Profe Alex say the various welcomes, on opposite sides of the stage each occupying a podium, they invite the school superintendent to give a word of welcome. I wonder to myself for a moment: “Is Lic Enrique here??!” but after a 15 second pause of silence with no Lic. Enrique, Seño Graciela continues with: “Is any representative here of Lic Enrique’s here to be able to speak on his behalf?” I am making bets with myself from my plastic chair: “How much you wanna bet they did not tell Lic. Enrique he was on the agenda?” And then it occurs to me that, this isn’t about making a space for Lic. Enrique because they expect him to come, but they leave the space as a necessary gesture of respect, even if he’ll never know it happened. And maybe they did invite him; I once saw a pig flying over Lake Atitlán.

After the pause ends, Profe Alex continues: “Now we would like to leave a space for the Auxiliar Mayor to give some words…” and I seize up a little. How many spaces are we going to open for no one to fill? We sit through another silence, the sounds of the antsy children in the gym decorating the pause, when Profe Alex continues: “O algún representante del Alcalde Auxiliar que puede hablar por parte de Él?” and I am thanking my stars because I see one of the padres de familia walking towards the stage. Wendy’s dad, the man who just served the whole student body bread and hot chocolate an hour before, takes the microphone.

The welcome(s) end and, am I hearing a Coldplay song? The upbeat violin and “I used to ruuuuule the worllllld” And the whole thing looks so rehearsed and downright inspiring! All 11 teachers walk down the aisle, followed by all of the students of the student body, Tercero (8th grade) followed by Segundo (7th grade) followed by Primero (Sixth grade). And I look at the faces of all of these students and I can’t help to notice how their growing bodies have changed in the short time I have known them. Rosillo’s thin little structure has stretched tall, her face is just as young as it was as it was in Primero, but she still looks like a little girl in a young ladies’ frame. Elias’s younger sister, I can never remember her name, has chipmunk cheeks just like her brother. I wonder if this endears me to her, or if it’s that she actually listens to me during my charlas, but I appreciate her. She looks like a young woman whose cheeks haven’t found out yet. Really, it’s so bizarre to see these humans in such an awkward time as they stretch tall like Gumby and their teeth are too big for their faces.

Middle school is such a strange and stunning time. In a year some of these kids have gone from being kids to young adults (very young, but nonetheless). The angst and sensitivity and struggle of these kids are just like those of all teenagers, be their lives polar opposite of my own when I was a teenager. Their bodies so perfectly reflect how I feel in service: growing every day and awkward every moment. This year it’s a little easier, but not a day passes that I am not the most unfitting creature in any context. And I’m reminded, even with how challenging it is to do this job and work in classrooms WHILE learning a second (and third language) and WHILE learning HOW to do the job in real-time, it’s all beautiful and it’s all tragic and it’s all worth it.

And maybe we’re not so different.

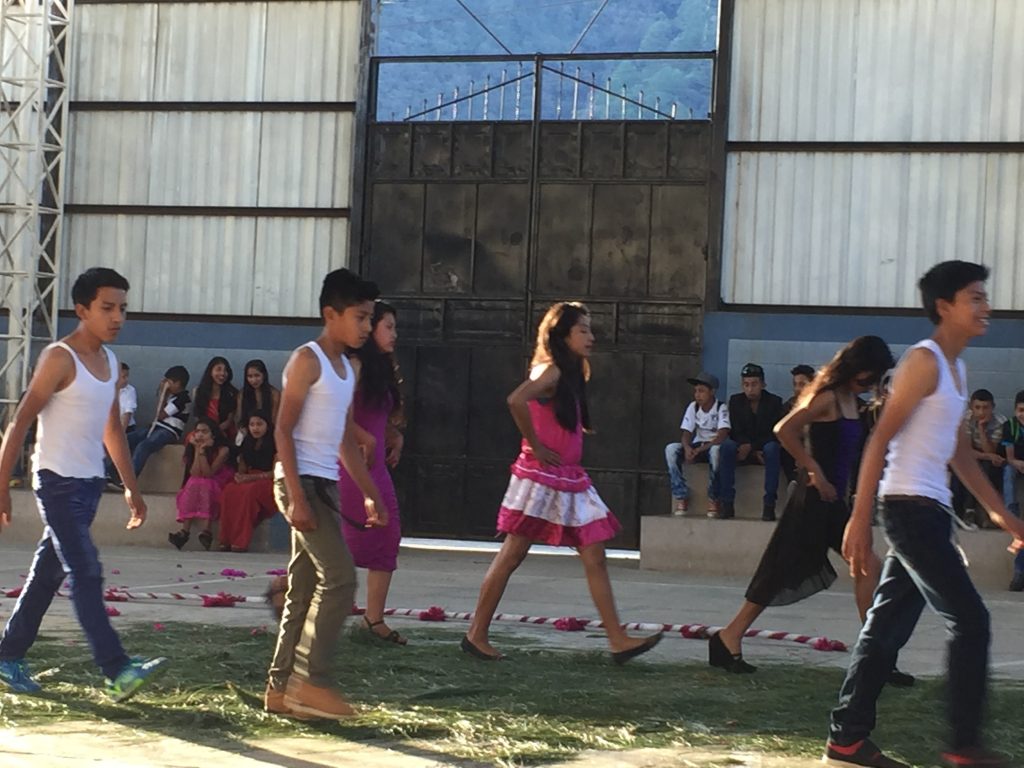

And just as I think that, the students and teachers file out and the students of Segundo are called up to perform their first “Artistic Piece.” I hear the notes blare through the speakers, whatever hit is latest on the charts. The students strut down the aisle wearing Traje Típico of Santa Clara and other regions, the finest traje that each of them has. And, as the song continues, it’s obvious who is in charge of the choreography as this dance was likely put together yesterday during math. There is always one head girl who planned and leads the choreography, in this case Juana Josefina. If there is any doubt who is leading the charge, you always know in the transitions. When the choreography changes every 16 beats, most of the students aren’t sure what the next move is, so they all look to the main girl to follow her lead. I must say, it’s true entertainment.

But then I see something I’ve never seen here in a year and a half: before my very eyes, the students are taking their traje off.

And I am taken aback: I grip the edges of my seat and I think “Is anyone else seeing this?” as I look around for an amen of ANY KIND. “What…. is….. going…….on?” Let me clarify: I went to a high-school where I had to put my palms by my sides to confirm that my uniform skirt was at least as long as my fingertips and only two inches above my knees. I was given a Promise Ring at the age of 13 so that I would wait for only one man to sleep with, we had a ring ceremony at school. And yet, Guatemala is the most religious world I’ve ever known.

Everyone in this country asks me: “What religion are you?” What they mean is: “What type of Christian: Catholic or Evangelical?” as anything else in the country is very rare (not totally non-existent, but close). They will ask you this in the first conversation, the first time they meet you. They will ask you like they ask you where you are from, “What religion are you?” It’s not personal, it’s like a fact on a profile. It’s like how hotel registration books ask you for your relationship status: Married, Single, Widow or Divorced? That took some adjusting.

And they are taking their traje off? The ones who ask me what religion I am like it’s googleable?

And yet, when I saw these students taking their most treasured traje off of their barely pubescent forms, no one else seemed alarmed or even phased. But I consider how live entertainment doesn’t often pass through the pueblo, Beyoncé and Bruno Mars don’t exactly make it out here. But this is live entertainment. This is it. And everyone comes to watch. We just have different concepts of what entertainment is. I’m the only one who is pinching myself as I look at the pile of traje on the floor as I wonder if I am dreaming or am actually, physically, sitting in this plastic chair with my phone dead in my purse and no use to me for getting proof.

Their new costumes were underneath the traje. They were bright-colored oddly-fitting dresses that they almost certainly purchased secondhand in piles shipped down from the US. Old prom dresses, easter dresses or dresses never worn and sent to the goodwill. Did anyone in the States imagine that these articles of clothing would go to decorate a middle-school talent show in rural Guatemala?

And before you know it, they are taking off ANOTHER LAYER. There is a THIRD COSTUME underneath which is another dress from the PACAs. No wonder their traje didn’t look quite as arranged as usual because there were two layers of dresses underneath.

As the song ends, the students trot off the floor and down the main aisle, each boy with a girl, the girls strutting and the boys just trying to keep up. I must say: some of the girls can take on this attitude of a “dancing girl,” hips swaying and heels kicking as if they are walking down a runway. But the other girls look truly lost. They know they can’t do it but, they must participate in the dance, and the critic and inner-comedian in me is feasting on what has just occurred in front of me.

Seño Graciela and Profe Alex are back at the mics, thanking the participants of segundo básico, when the lights go out. What kind of talent show would this be with power? I guess in this case it wouldn’t matter if the projector was here to do my presentation.

After 20 minutes of sitting in loud darkness, children running up to me to yell my name and running away, the lights eventually come back. Sometimes lights go out for full business days, “for maintenance” they say, so I was relieved and a little surprised to see my own body again.

We continue on to the next event and after the teachers do a beautiful “baile folklórico,” the familiar music and choreography playing as the female teachers hop from one foot to the other, barefoot, carrying baskets and forming a circle to complete the dance. I notice how high Seño Graciela hops off of the floor, so young and happy. I feel old. I wonder if I have the energy to hop that high, over and over again.

I look to the edges of the gym and see several familiar faces, the students from Tercero Básico who graduated last year. To be honest, I am surprised. The students who scoffed at me, who treated me with (varying) levels of respect and paid attention to my charlas, as I was so nascent at the job.

Eventually in the sequence of events, I am called up for my “artistic piece,” a song. I grip the microphone as I say “Good Evening” to everyone in K’iche.’ “Shoka’ap!” I run the list off in my head: “Personal docentes, padres de familia, Paquip en general.. que tengan la mejor de esta noche.” If you skip this part, it is extremely rude. You have to represent each group of people individually in the room. When every speaker or participant steps to the mic, they great everyone in this manner. Even after everyone present has been acknowledged by everyone else, you do it too. Everyone greets everyone, every time. Every time I do this greeting I am left slightly insecure as it is so foreign to me, wondering if I really did it correctly or if I offended anyone by omission. I continue as I explain in Spanish that, as this is the noche cultural of this years anniversario, I would like to share a part of my own culture which is the national anthem of the USA. I am from Atlanta, I explain, but I am grateful to be here and be invited to participate in this special night in Paquip.

With that, I sing an a cappella version of the US national anthem. When I finish there is silence. Normally people break out into cheers at the end of the National Anthem but here nobody knows what the heck I am saying. I must say, as cool as it was to hear my own voice cresting the hills of the mountains of Paquip from the sheet volume of this microphone, a part of me was relieved that only I understood the lyrics. The lyrics hit me in a strange place though I’ve heard the song a million times, sung it a bunch of times, too.

It’s about Peace Corps guilt. It’s about privilege. It’s a feeling that comes from the ambivalence, anger and doubt that I feel as I go through the daily interactions that come with this job. I sang words which are full of appreciation and pride for the USA: “The land of the free and the home of the brave…” but these people have lost their close family members in the name of trying to cross the border for a better life. They have either been raped, injured, killed or cannot return to their country until they return for good. Because they don’t have the proper (read: expensive and extensive) paperwork. I thought “The land of the free and the home of the brave…” if you were lucky enough to be born there.

Happy that my piece is over and disappointed that I can’t report any of this because I didn’t present on my country, I walk outside to see what snacks I can find. It’s raining and my umbrella comes in handy. I’m grateful I brought it, half of the time I forget it but we are now in rainy season. I asked the ladies: “que me ofrecen?” and they list off the usual refas/snacks: corn on the cob, chuchitos, tostadas and chicken sandwiches (they’re not what you’re thinking). Juan’s mom from last year describes the corn as galan galan as I question the price of 5q, and I eventually give in and buy the corn. I pay less for a 15 minute-ride to Paquip. I ask for all the fixins: mayo, ketchup, hot sauce and salt. This is called “Elote Loco,” crazy corn.

The owmen were all huddled under one awning to stay out of the rain. A line was forming to buy more snacks, everyone peeling their quetzales apart or balling up fists to accommodate their coins. They asked me the usual questions before I walked off with my corn. “Do you have a boyfriend?” This time they ask because they know I have an answered cued up: “Tengo tres novios: Xib’inel, Xarakot y Ajluta” which always meets a host of laughter. I’ve just the names of three types of ghosts in K’iche’. It’s like I’m their own personal stand-up comedienne.

I dodge muddy puddles and let the corn kernels invade my gums as I ugly-eat this corn on the cob. You just can’t be cute while you eat Crazy Corn. You must be CRAZY. And the corn was crazy good, worth every q.

As I prop myself against the wall for a change of scenery, I see the faces of the students who graduated from this school last year huddled by the side entrance. I realize: “This is like homecoming!” The school anniversary celebration is like homecoming. And it all makes sense to me.

This event continues to unfold around me and the feeling I have is still the oddest: it’s a combination of being known but not belonging. But it feels as comfortable as I have ever felt in Paquip, and as much a part as I’ll ever feel after 1.5 years of showing up.

At 9:00pm, I decide that I’ve been here long enough. I went to “get Wendy,” to “get Juana” and I sang the national anthem in traje típico. I watched the artistic pieces. I listened to reggaeton on reggaeton, the 5 minute national anthem, and I ate the crazy corn. I saw that my neighbor and her husband and kids were headed home. They either had a car or had a friend with a taxi. I asked: “May I ride with you?” and they responded: “Jo!” (Let’s go).

I went back into the gym to hug the teachers and said “I liked everything!” And Magdalena replied: “Well how could you like everything, you are leaving early.” And I said: “Well, everything I saw, I did like!” And she said: “Ah, está bien Licenciada.” I don’t know why that response was necessary but okay..

We rode home through corn fields in the dark. I wondered if I would have to pay for this ride. We didn’t talk much on the ride home, but I was grateful for this mysterious taxi appearing to take me home. When we got home, the taxi driver charged me five. I was fine with it and tiptoed through puddles up to my door, unearthing my key from my purse.

I would charge my phone and reconnect to the world through invisible lines again. But for one night, I was only a person without a phone singing the national anthem in a pueblo echoing across the hills of Guatemala. I did good. I went to sleep and waited for another Guatemalan sunrise.