On this quiet Sunday afternoon, I was sandwiched squarely between an older, sleeping man and a younger woman in bright coral and pink traje with plastic beading shouting across the neckline. I don’t love this about modern traje: the younger girls like to decorate the already stunning patterns with fake diamond embroidery, it’s what’s that GRE word?, meretricious: gaudy. I pulled my heels up to my butt, this is a cheap travel trick to make more space on the bus. It’s cheap because you can’t make yourself smaller, try as you might on the stretch of road between Santa Cruz and Chichi.

We chug through gray and green, the earth rainy and dripping in growth all around. This country is feverish with leaves. My mind had focused up for this three hour-journey and I was perfectly amused to pair the rich moments from the weekend with delicious words and metaphors as we leaned into the curves and onto one another. I listened to the song “She Used to be Mine” from the musical Waitress, music by Sara Bareilles, and it finally occured to me that this song isn’t about me yet, but it will be. When I am done with service, I will think back on my volunteer self and lament her departure. Even though that sounds sad, it brought me great comfort because I’ve listened to the song throughout service. I will carry it with me as a recuerdo. Eunice introduced me to it, and I have her to thank.

We chug through gray and green, the earth rainy and dripping in growth all around. This country is feverish with leaves. My mind had focused up for this three hour-journey and I was perfectly amused to pair the rich moments from the weekend with delicious words and metaphors as we leaned into the curves and onto one another. I listened to the song “She Used to be Mine” from the musical Waitress, music by Sara Bareilles, and it finally occured to me that this song isn’t about me yet, but it will be. When I am done with service, I will think back on my volunteer self and lament her departure. Even though that sounds sad, it brought me great comfort because I’ve listened to the song throughout service. I will carry it with me as a recuerdo. Eunice introduced me to it, and I have her to thank.

The ayudante slowly makes his way down the aisle and asks for payment. I quickly pull out 10 quetzales, ready, and he tells me the price is 15. Funny, yesterday the same route cost me 10. I respond quizzically and say: “Is it because it’s Sunday?” And he said: “Sunday or any day, it’s 15.” I should have said: “Is it because I am not from here?” At the front of the bus, above the windshield, the words are pronounced: “DIOS TODOPODEROSO.” As I burrow through my bag to find my foreigner fee, my thoughts are as follows: is todopoderoso one word or two? and If Dios is all powerful, why am I being jinxed out of 5q?

This is not my normal route, and this ayudante took advantage of me. I can spare 5Q but is it not the principal of the thing? I even asked the girl next to me, is it 10q, she tacitly confirmed that it was but did not come to my defense. Apparently you do not dare question the ayudante, TODOPODEROSO. I gaze at the face of the driver in the wide rearview mirror, his expression unchanging, bored, todopoderoso, another man calling all the shots for me, taking my bus fare+ and pushing the pedal that propels me across the slippery pavement until I am home. Ni modo, this post is about anything but men abusing power.

This post is about My Weekend with Brócoli.

On Saturday I arrived to Santa Cruz del Quiché, having paid the fair price of Q10. I sent another message on WhatsApp: “Estoy al lado del Regi’s” and I called my Mom, I never know how long people will take here so why not use the time I have? I explain that Brócoli is a person, that I am visiting him and his family for the weekend. Mom and I share a few minutes of chit-chat when I see a guy in an orange and blue flannel-type shirt with black jeans (with like rips, but fabric under them so, trick rips?) and bright red and white Nikes that are squeaky clean. Maybe he is estrenando, wearing them for the first time. Guatemalans take pride in wearing clean shoes, all I have to say is: it’s a wonder with all the fecal matter you pass on a pueblo street. The ensemble was not garish, it was Brócoli. I pat him on the arm as an occupied greeting (being that I’m on the phone), and he pats me back. I should have stopped and kissed his cheek but I was dealing with the awkwardness of greeting a stranger who will be my host for the weekend by being occupied on the phone. I hang up and he says “Vamos” and like that my desconocido weekend host and I walk through the terminal. He waves at folks he knows as people stare.

I do not know Brócoli. When I went to Esly’s wedding in August (Esly is another volunteers’ host sister), I rode 6 hours to Chicamán, bus to bus to bus to bus to bus. I arrived to a rainy night in the market, Topo (a stranger who is in a banda heavy metal his exact words) treated me to churrasco, grabbing it to go and making our way to Tony’s house. Mynor appeared while I was knuckle deep in churrasco. I should have gotten up, kissed his cheek and greeted him, but I was awkward and unsure of who he was (sensing a trend with me and men and greetings?). He probably was just as awkward and unsure about me.

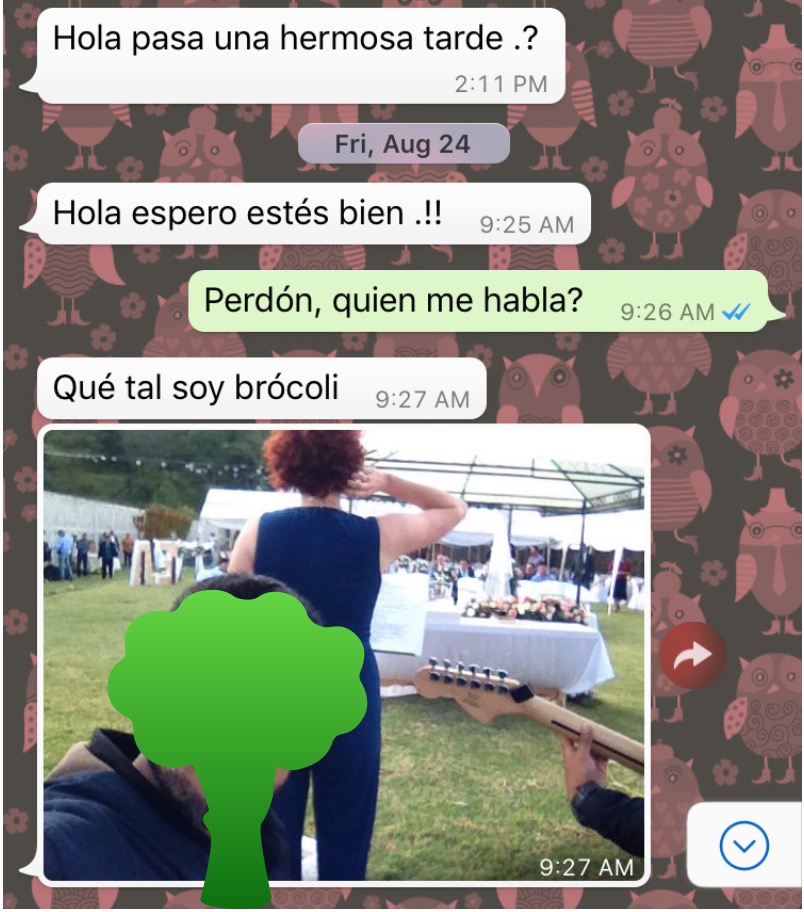

Soon, Mynor, Topo and I were sitting in the café/living room with a mattress propped on a wall, singing through the songs: Perfect, Thinking Out Loud and Hallelujah by Jeff Buckley (I’m just the singer, not the song-picker). Tony said “Tomorrow we will run through it once more with Brócoli.” I repeated: “Brócoli?” and their response: “yeah he’s a friend playing the drums who will come from out of town in the morning.” I met Brócoli the next day 30 minutes before the wedding. We ran through the songs while Brócoli played the Peruvian caja, The Box, providing percussion. It started to rain at the outdoor wedding so we sang all three songs at once. After we finished the songs, the three men and the three instruments disappeared without saying goodbye. Later in the week, this:

Yeah, I think he sent me this strangely staged selfie, featuring my back, as a means of identification. Guatemalan AF. After a few long phone calls, and several text messages: “Did you eat lunch?” “Yes” “Provecho” “Gracias”…. “Did you eat dinner?” “Yes” “Provecho” “Gracias” I asked him if he would come visit Santa Clara, he said “Sure if this guy gets me some money I owe him then I can come this weekend.’ Then his grandmother had to have surgery. And I realized that if I was going to meet up with this vegetable, I would be going to him. So I said: “I’m coming this weekend. Can I stay with your family?” and that was that. I even had to ask for his home address to report Whereabouts to Peace Corps.

As we walked to his car, I was reminded of Brócoli’s height: almost as tall as me. Even though that’s a great deal taller than men in Santa Clara, I felt a twinge of guilt like it’s my fault for being 5’7”. Women are taught to be slighter, smaller, less than. I wondered: Does he notice that he is shorter than me, or care? We stopped at a rust-orange Datsun and I am in Heaven: no ayudante. There was no handle to the passenger side door but he slid in and pushed it open for me. He told me he couldn’t find me so he asked the guys at the terminal for a ‘mujer Americana.’ I responded: “You didn’t say gringa?” And he said: “No, I didn’t.” I was amused that he didn’t call me on the phone, like anyone in the States would do, he just asked some guys standing around: “Ay, where’s the American lady?”

Classic rock comes on the radio, which I remember that he loves. One night he played the guitar and sang while we were on the phone. He tells me: “First I am going to take you to The Ruins” and I immediately feel a little funny. Does Brócoli want to go to The Ruins? Or is he just taking me to take me? And another logistical concern: Who is going to have to pay? Guatemalans pay for everything when you visit. I am going to feel awkward because he has told me he is currently working as a volunteer and doesn’t get paid. Do I offer to pay? The Datsun slowly scales the hills as Brócoli tells me that his family will serve me lunch, and that we will later go to a lake. I assure him that I am very onboard with all of this and thank you for hosting me.

Brócoli is a PEZ dispenser of Spanish words I don’t recognize. Spanish is his first language; the first language in Santa Clara is K’iche.’ While I speak Spanish with my host family and work counterparts, I also speak K’iche’. Regardless, the level of Spanish that is spoken in the pueblo is slower and simpler. I often envy the volunteers who live in Ladino sites because they are exposed to faster and more advanced Spanish. But then I snap out of it, my host family is the best, we can speak basic Spanish together or speak pig-latin. The sign to The Ruins displays the entry price: “5= Nacionales, 30= Extranjeros” about 84% more for me. I point out the difference to Brócoli and he says: “Don’t worry!” and runs in, paying for two locals before they see me.

At the entrance of the museum we pause. The significance of Q’umarkaaj in K’iche’ is house of straw (or- something of straw). Brócoli moves quickly from thing to thing, investigating. I say: “you’re very energetic” and he says” “todo eléctrico.” The descriptions are in Spanish which Brócoli notes: “I thought there would be an English translation provided..” We pause at a painting of a war and he narrates: “This is the history of this land” and I say: “Where are the women?” and he says “The women didn’t fight in the war.” We continue outside. He explains that many of the ruins are still below us, but ‘escarvar require recursos’ and tiene razón, he is right. On the other side of a hill there is a clearing with ruins on one side, and Mayan ceremonies happening below. “I attended one of these ceremonies” I tell him. There are fires and people speaking over them. We walk through the ruins and he pauses as I snap pictures. It’s really lovely out.

We keep walking until we face a black, ominous opening to a cave. A chucho has joined us, anxious for food we don’t have. I tell Brócoli to stand by the opening and I take two pictures. He puts his arms out wide like he’s standing in the rain, which is exactly what I do in pictures when I don’t understand why they are being taken. We walk in and I feel the dampness of under-earth. “If it spooks you out we can leave,” he says but this is my favorite part so far. He leads the way, turns on the linterna on his phone and I follow suit. He says: “This is where people used to escape.” “To where?” I ask, but I don’t remember his answer. There are several tunnels that dead-end. I notice all the inane scribbles on the wall by bored and horny teenagers: hearts with names and “TKM” Te Quiero Mucho. “You can sign something if you want” he offers, but I pass. As we begin to walk out, he positions his phone lantern to see if I can get a good picture with mine. The chucho is still with us, not at all spooked. I recall the names of ghost in K’iche’: Xib’inel, Xarakot y Ajluta. I can promise I’m the first ever Gringa to utter ‘ghost’ in K’iche’ in this K’iche’ site. I can’t guarantee it, but I can promise.

As we leave I nod to the Indigenous woman uttering words to the spirits, and Brócoli and I toss around the topic of religion. I ask if he does yoga, and he says no and explains his understanding of the spirituality of yoga. I explain that for me yoga has simply meant flexibility and exercise. He tells me about the different beliefs of the Mayans before Spain invaded and how the religion changed to Catholicism. I listen as he talks, still adjusting to the pace of his speech. He leans over and picks up a pile of moss. I am from Florida where moss is a hassle. What does he want it for? I say: “what’s the name of this in Spanish?” and he says: “Well here we call it pashte” And I laugh. A pashte is a wiry sponge for washing dishes, and it does look like pashte. I look it up: “moss= musgo” I say. “A sí, el musgo.”

I help him reach for the musgo from the branches and he laughs at how high I can reach. We begin to walk back to the car. I am happy to be back in the Datsun and we make our way home, his home, which is another unknown place to me. Brócoli drives through the streets under rules I can’t perceive- who has the right of way? I don’t know- but we slow to a stop by a garage door. I grab my purse and he already has my backpack and sleeping bag in hand. He slides his hand through the window and pulls the latch, a completely normal practice to me now. As we walk in I say: “con permiso” to which he responds “pase.” Perfunctory, but you gotta say it. “What is your Mom’s name again?” I asked, whisperish, and he said “Francis” I echo “Doña Francis” and he replies “Cabal.” Exactly.

The front of the house is a long stretch of patio with plants hanging overhead and a car parked inside, the walls a happy, but not garish, green. He sets my bags on the outdoor living room furniture. He says “Siéntese” so I do. He is very concerned with being a good host. Seconds later he is walking back to the Datsun for the musgo, if I had a quetzal for every time I said “I left The Musgo in the Datsun!” He returns with the musgo and leaves it in a pile on the concrete. We walk upstairs to meet Doña Francis. I am prepared to meet a tall, strong woman with a long, black braid, wearing traje, reigning supreme over her kitchen, iron or stove. My own expectations offend my sensibilities, and I should remember that a Guatemalan Woman is a force you can’t predict or imagine.

On the second floor there is an outdoor landing, with a covered area with couches, seemingly freestanding appliances and machines: a laundry machine, a stove, some extension cords hanging from the ceiling. They machines aren’t resting against walls (probably because rain could fall on them) so they stand in the middle of the patio. We’re not inside but we’re not outside, either. It took me a while to adjust to this element of Guatemalan homes. The concrete has been swept and cleaned this morning and plants have been kept with care and adorn ledges and walkways. The lamina always detracts from the view but it is normal. It’s like a corrugated, wavy tin material that serves as a roof (cuz it’s cheaper than concrete block) It covers over the walkway on the first floor where the vines extended across the ceiling in the entrance, where the musgo will go.

Doña Francis is much shorter than Brócoli, so you can imagine I had to lean over for our cheek kiss. She has a sweet smile, her hair is dyed a light auburn like mine. There is a quiet strength in her eyes, a diligence and a desire to be ‘behind the scenes’ but surrounded by people. I dispense at once “Un gusto conocerle y gracias por recibirme en su casa..” I almost sing it so she knows I mean it. She smiles and says: “Siempre está en su casa” and a la vez: “tienen hambre?” are you all hungry? and yes, I always have the hunger. I will learn that this is the type of woman who loves to serve others, and I don’t mean food (it does include that) but in general.

I hear talking in the kitchen. I get the sense that I am in for a reunion. Brócoli pushes the fly-curtain aside, and gestures to a seat at a long kitchen table: “siéntese.” “Te gusta café?” he asks, and is up again. I say: “Claro” and prepare myself for the glass jar of instantaneo in my future. Two ladies stand behind the tiled kitchen counter, quiet but curious. As Brócoli introduces me I kiss each cheek and say “un gusto conocerle” a cada una. There is one young girl, wavy haired and in a dress with the waist ribbon untied, who stares up at me and wants to smile and wants to talk so does a little bit of both, but mostly stares.

More family trickles in; another Guatemalan feature: the family trickle. Brócoli continued telling me who is who but I could not keep sobrinas apart from primas apart from hermanas apart from tíos apart from me. But I know that Brócoli’s mom is his mom and she served us like a waitress. She did not sit with us, she simply set two plates of rice, a drumstick of chicken, and a salad of cucumber and radish slices in front of each of us on large, glass plates. I spy tomato sauce but I am missing hot sauce, nowhere a la vista. I wonder if Doña Francis might bring it after the basket of tortillas wrapped in napkins, but it does not appear. Ni modo, when the tortillas arrive Brócoli begins, diving his hand under the woven napkin to retrieve his first tortilla. He says to me come (eat) and bows his head over his plate. He knows I am not religious, but I quickly feel the outsider just like I do with my family at meals, them praying and me looking neutrally at the food.

I unwrap my fork and knife from the paper napkin and remind myself I cannot go HAM. Guatemalans eat slowly, they use the tortillas like hockey sticks to entertain the other ingredients, and they don’t shovel anything down. I notice that Brócoli eats slowly and I try to match his pace. While family comes in and out, it’s mostly just he and I sitting across from the table, talking. “Come con confianza” Doña Francis says as she reappears. I say: “Gracias, es muy rica la comida.” I feel like I need to tell her four times, because I feel bad when Stranger Moms serve me food. But I know that this is how it is so I say it only once and continue eating.

I begin to joke with the family about Brócoli at the terminal: “Brócoli asked ‘where is the gringa’ and everyone at the terminal knew my exact location’” He retorted: “I didn’t say that, I said: “Hay una mujer americana’ and I said “yeah but I bet they responded with ‘gringa’” and he smirked. Correct. Then I imitated Brócoli at the terminal: “Que ondas Vos, Hola Soy Brócoli” extending my arm out like I was Big Man On Campus and everyone laughed, especially his sobrinas. I noticed that his sister and sobrina were baking. Brócoli said: “Cori le gusta hacer pasteles” and I oohed as if on cue. Later, as a means of making conversation I asked: “Are you all baking a cake now?” which in Guatemala means: “I would like you to bake me a cake, please and thanks.” Oops.

Another Tío appears and sits at the end of the table, Doña Francisca magically appearing with a plate of food for him. José is his name, I think. Another young boy, 18 or so, appears with glasses and braces which are two signs of wealth. As I speak to the Tío who eats casually and barely cracks open his mouth when he speaks. He tells me that he thinks his children should learn K’iche’ like me. (Brócoli keeps mentioning to everyone that I speak it). Tío José calls to his kids in the other room and one medium-sized adult appeared: 13, the ripe age of in-between.

She stares at me and speaks slowly, like Spanish is her second language, but really she just likes to send the words through her mouth like pushing mail through a slot (just like her dad!). The message gets to me in syllables. She’s awkward but calmly enamored with me. Then a chubby-cheeked 8 year-old walks in and I hear him called “Garlic” in English, como Garleek. Is there an Aunt Rudabega? By the end of lunch I think I’ve met everyone in the family, plant, mineral, vegetable, gotten up to kiss every cheek, guessed every child’s age and left enough time after eating to visit, to confidently say “Muchas Gracias” which is how you formally conclude a meal.

I get up to leave the table. By the time Brócoli and I were getting ready to go, the Cori and her niece said: “We are going to make you a cake!” I felt bad but I should have known. I oohed. They asked “what kind do you like?” too which I said: “All the kinds!” Brócoli and I walked downstairs to leave.

Sonia followed me, the eight year-old with wavy hair, and I began to hang the musgo from the vines. Amidst the adorning Brócoli looked at me and said: “I really like flores.” Sonia pulled the musgo apart and I reached on my tippies to hang them from the edges of vines. Finally, something I’m still not tall enough for in this country. “You get the idea now?” he asked, and actually I did. It made the entry even more inviting and made the vines look alive.

We are in the Datsun otra vez when I get bad news in a text, someone from home’s pregnancy did not work out. I tell Brócoli. This subject is not taboo like it is in the States. Your loss is kind of everyone’s loss, here, and loss is more common in every sentido. He asked me more questions about the situation, told me he was sorry. He told me his sister, the one who was baking the cake, just lost a pregnancy too. I wondered how she is handling it? She looked perfectly fine, not at all painted with loss. Her son is Garlic, he told me, “so it is different because she already has one son” he reasons. But loss is loss, it doesn’t matter if you already have children when you love and lose another.

As we rolled down the street he said: “pinchirrilo.” I echoed: pinchirrilo? “That’s what you call an old car like this, a pinchirrilo” The word itself was amusing to him. It must make him recall when his friends make fun of his car. “We are going to Lake Lemua.” What does that mean? I ask. It’s in K’iche’, he doesn’t know. He asks me if I would like something to drink and I am relieved. It’s not because I prefer to drink during the day, but at this particular moment with all of this bombardment of Spanish and human and newness and produce, I was up for it. He pulls up to a tienda, and I stay in the pinchirrilo. No vale la pena to walk into a place long enough to confuse everyone with my foreignness only to walk out. We pull up to a calm lake and I extricate myself from the pinchirrilo. There are two fold-out seats in the back, one red and one blue, and we arrange ourselves just above the grass as he furnishes two Quetzalteca Mora, seltzer water and 7up from a tienda black bag. We choose seltzer as a mixer, he shakes the Qtec to mix it and pours it into two styrofoam cups. “Cheers” I say, tapping his cup to mine, and he says: “Salud.”

There was a young kid and a younger kid fishing next to us. I noticed that they did not use fishing poles, just cord wrapped around a spool. These kids have no nostalgia for fishing with fishing poles I thought. Brocoli confirms what “fishing pole” is in Spanish and I have to get my notebook to write it down, my phone has died. My list is getting long: preplégico– perplexed, carecer– faltar– to be lacking, joder is slang, a word that has a million meanings according to the internet but it means ‘to screw something up,’ perfil bajo= low profile, apoderarse– to seize, to get control of, to overcome, trasfondo– a second meaning (like double entendre), Escocia– Scotland, sensibilizar– to sensitize, to raise awareness of, solidarizarse– bring together, show support, show solidarity. These are beautiful terms that I have only imagined until this moment. Brócoli is pulling them out of the sky and adding them to ‘tu léxico’ he says.

Where am I? Sitting by a lake with a welcoming stranger named Brócoli drinking Blackberry flavored Qtec out of a styrofoam cup. I was not mad but still, what?

Along with all the other Spanish gymnastics in my mind, I tried to stick with “tú” as much as possible, not forgetting entirely this other conjugation at my disposal that I almost never use. Eres instead of es, estás instead of está, dijiste instead of dijo. My host family, in spite of how casual we can be with anatomical terms in K’iche’, still use usted with each other. For me it’s been too complicated to switch between tú and usted. It’s too confusing with all of the formalities, titles and norms, or watch me haul off and use “tú” form with the mayor. But with a person of confianza, or a person your age in an informal setting, you can tutear, or use ‘tú’ form. And I don’t want to sound like a librarian, so I tutear. I tutear with Brócoli.

Conversation wandered to things you talk about when you are getting to know a person at a lake with Mora Qtec in styrofoam cups. I don’t remember how the conversation wove itself but I had to put my hand up to represent: ‘espérese’ to take notes. He did not get impatient with my constant questions: “What does that mean?” We talked about religion, the USA, I remember that he referred to Freud, other philosophers, and by the end of the hour and a half of talking, I had deemed him ‘El Filósofo.’

We talked about family, his dad who lives in the States and my parents who live in a different world from me even when we are under the same roof. As it started to sprinkle, ripples on the water as visual proof of rain, Brócoli quickly grabbed the chairs, folded them and stopped: “Wait, unless you like being in the rain?” The truth is I needed to pee. I told him so and he checked out the concrete outhouses nearby. I heard him mumble something about “there might be feces” as he went in to investigate. We got into the pinchirrilo.

As we pulled up to the entrance he said: “the only thing is, you might get wet” as we were about 15 feet from the bathrooms and rain was falling. Guatemalans associate a little rainfall with instant cold and instant death. You should have seen how fast he grabbed those chairs and got them into the Datsun at the second sign of rain. I told him “no importa” and opened the door. He said: “You can walk under this side so there’s less rainfall” referring to the tree-cover and I said: “No hombre!” dismissing the silliness. As I zipped up to the sanitarios, I knew I could pay for this myself but Brócoli already had the coins out. To pee, dos cincuenta. The bathroom guy had piles of toilet paper stacked, ready to dispense. And then Brócoli asked: “Do you need toilet paper?” I said: “Sí.” Females always need paper, homie. That was awkward. I took the paper and briskly disappeared into the bathroom, made no attempt to flush as I knew the water would not be in service, washed my hands over a bucket with soap, even!, and met Brócoli and the worker both looking out over the rain. I asked “Cuánto?” and Brócoli said “Yo ya pagué” “Oh gracias” I said and we headed back through the rain to the Datsun. I waited for him to push the door open from the inside.

As we drove home I said “Brócoli, eres buena onda.” He said: “Gracias.”

He asks: “Do you like atol? What type of atol do you like?” Atol is like a hot smoothie, made out of anything from rice and sugar, milk, chocolate, corn. And I tell him: plátano or elote (plantains or corn- don’t knock it ’til you try it). We pull up to a house where ‘there is a señora that makes atol.’ We walk into a simple garage-converted-restaurant with full tables, a good sign, and everyone’s conversation nearly halts as a Gringa enters. Maybe it’s not so much that I am a Gringa as that I ‘ando con guatemaltecos’ that’s so mystifying. I don’t know, I think these people would be just as confused if I traipsed into this ‘señora with good atol’ garage/restaurant by myself. At the front ‘counter’ you order and then you sit and wait. Brócoli asks what types of atol there are and ‘the señora’ only mentions leche: arroz con leche y arroz con chocolate. I am disappointed because I phased out of arroz atol a year ago. Brocoli asks: “Which do you want? Chocolate, arroz con leche o quartiado?” I said: “What’s that?” “Es una mezcla de..” and I put my thumbs up. “Aguardiado.” I say, saying it wrong, as I furnish my notebook once again.

We don’t talk much, slowly sipping our atol. The rain outside is a perfect pairing for atol. In my mind it is hot chocolate, warming our fingers through the glass mugs. Quartiado. Aguardiado. Eventually I figure it out and write it down.

I think we are tired, or maybe it’s just me, Spanish and family and food and cake and all of this newness. You see, it wasn’t until my second year in service that I used Spanish on the weekends (unless I stayed at home, of course). Normally I would meet up with volunteers, watch movies in English, write (in English).. But spending whole weekends in Spanish is a whole new level and requires frequent snacks and breaks. We decide to go home and when we arrive, ‘con permiso,’ the kitchen is buzzing again. There is a cake the size of The Grand Canyon on the table, not with real icing but whipped cream. I can dig it. But I do miss icing. I’m relieved to see it’s not a cold cake or a wet cake, may they burn in the inferno of lackluster gastronomy. Nevertheless these ladies whipped out a huge cake in two hours, almost on command. I know that this is a sign of hospitality in Guatemala and I don’t overlook that for a second. Even as a stranger, I am the guest of honor.

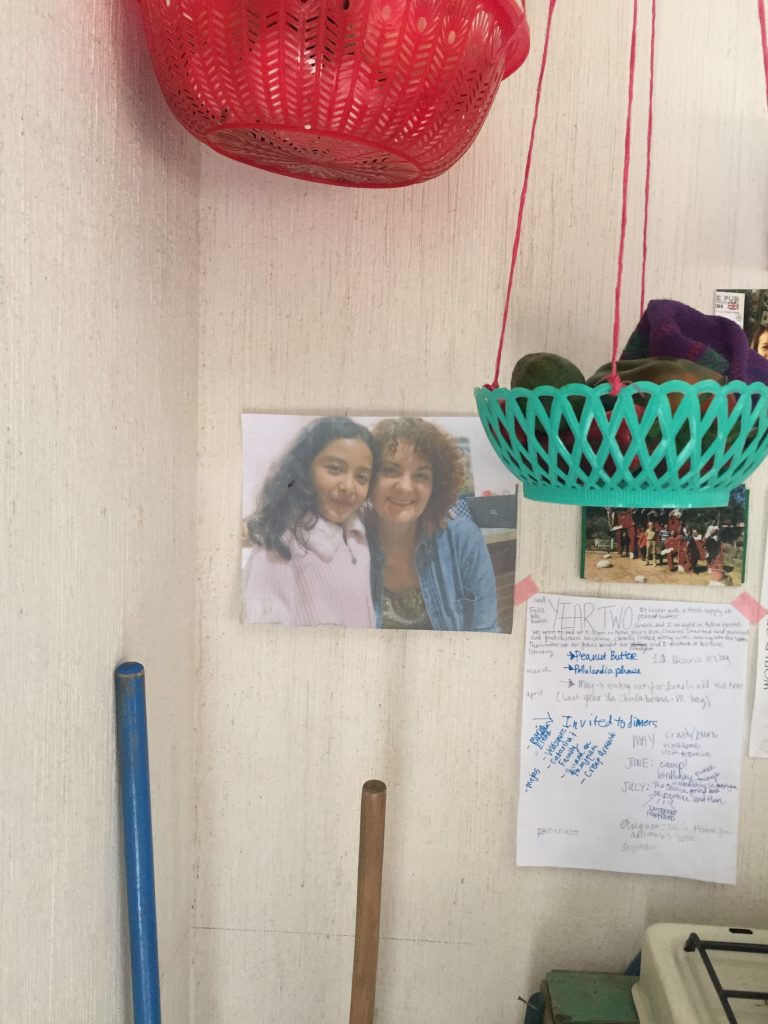

In the time I have been gone, the younger kids attached to the thought of me.. that is, the girls. The boys, José and Garlic, are glued to tablets and telephones much like Mike Teavee. The smartest technology in my house is Abuelita. Soon Sonia and I are taking selfies and the 13 year-old, I can’t remember her name, is telling me more about her family in Houston. It is obvious that I am a bridge to their family in the States. I am some sort of ambasadress for the culture that many of their aunts, cousins and siblings call home. I wonder if this endeared them to me more than it would another guest, but I can’t be sure. What I know is that my presence was special to them, interesting, compelling, and soon I was writing down my name for facebook purposes. Sonia laughed at my antics and said: “I am going to print this for you before you go!” and I was surprised. Printing requires a photo development machine of which there are none in Santa Clara. In 10 minutes she is back with an 8×10 of our two faces smooshed together. Now I understand, she printed it on a computer printer. Still, I was touched by the gesture and it’s hanging on my wall.

I sing along to the English playlist they have streaming on youtube, I know all the songs. They chatter about how I know them, even though I am casually singing along. You would never walk into a home in the States and hear non-Spanish speakers listening to Spanish music on the radio. I mean, maybe. Their families in the States are listening to this music, maybe they want to be connected by the same melodies.

Next I was helping the one with braces with his English homework. He wanted to learn, “though the pronunciation is a real challenge” he told me, like his problem is unique and I’ve not heard this from every other Guatemalan learning English. “I like the language and I want to learn but ‘lo que me cuesta es la pronunciación.’” I never know how to react to this. Pronouncing English is not hard for me but I understand why it is hard for them, yet, I cannot change the fact. So I have to empathize again with their plight: yes, yes it is hard. And now I know that it is because of how many times I’ve heard it. Once I’ve helped him finish translating his scene at the doctor’s office, he kisses me on the cheek with ‘muchísimas gracias’ and disappears behind the curtain protecting the kitchen from flies.

Now it is time to eat and Garlic is at one end of the table and José at the other, tablets and cell phones in hand. They’re like mischievous technology monsters completely submerged in pixels who occasionally come up for air and interaction with heartbeats. Scary what the world is coming to, developed or developing.

We eat dinner, served by Doña Francis, and it is eggs and beans. Eggs and beans. Eggs and beans tralala. It makes me grateful that my host family doesn’t eat eggs and beans every night, but hierba isn’t much better (well, says me). When the tortillas grace the table, Brócoli prays and I begin. Garlic and José are quick reminders why I am so relieved that I don’t have mini-mes. Their eggs and beans and tortillas are not in concert, they are in conflict, and they end up on chairs, tables, tablets, phones, floors. Ugh. Brocoli looks at me and says: “Yeah, sometimes I think that there are enough people in the world and maybe I don’t need kids.” I am so 100%, syllable for letter, in concert with this philosophy. Did he hear the cymbals clang in my brain?

Later, I’m downstairs and ask Brócoli to point me to the bathroom. H escorts me there, walks in before me to give it a quick once over and walks out saying “Dale.” Go for it. This is what ayudantes say to drivers when they’re backing up and they’re in the clear. “Dale dale.” It appears that Brócoli missed the smudge of what I can only assume is poop on the wall. I try to ignore it but I can’t. This is why I can’t have children. Poop on walls. The next time I use the bathroom, it is gone. Doña Francis The Magical swooped in, if I had to guess.

Finally we have entered Brócoli’s room. Just me and Brócoli. I am taking it all in: vinyl records don the wall, pictures of him playing the guitar, singing, a closet set-up with all of his clothes and shoes neatly arranged, a huge TV sitting on a wide console. There are several framed things written in English, like the kind of quotes you find at Hobby Lobby and Old Folks’ Homes. I think Brócoli can speak as much English as K’iche’, so I ask him if he knows what it means. He says he has an idea but asks me to translate. It’s a Bible verse, probably something he found in a PACA. But then I remember that we romanticize French in my culture too. I have had words on walls that I did not understand but put up ‘cuz it made me look classy. “All Creatures great and small…. The Lord God made them all” I finish translating. He turns on the TV and tells me to sit on the bed as he takes a seat on his drum pedestal.

He chooses a channel that’s dubbed over in Spanish and it’s called: “Morbidly Obese.” Sexy. The man in question weighs almost a thousand pounds, we are both quickly enmeshed in his plight to lose weight to live. Honestly, it’s graphic. It’s not what I imagined we would be watching. I ask Brócoli if he is comfortable sitting on this pedestal, and I realize that I have not met a man like this in a long time. He doesn’t try to make a move even when I am in his room, with the door closed, sitting on his bed. First I’m a little bored and then I remembered the wisdom of There is more space to get to know a person when there is more space between you.

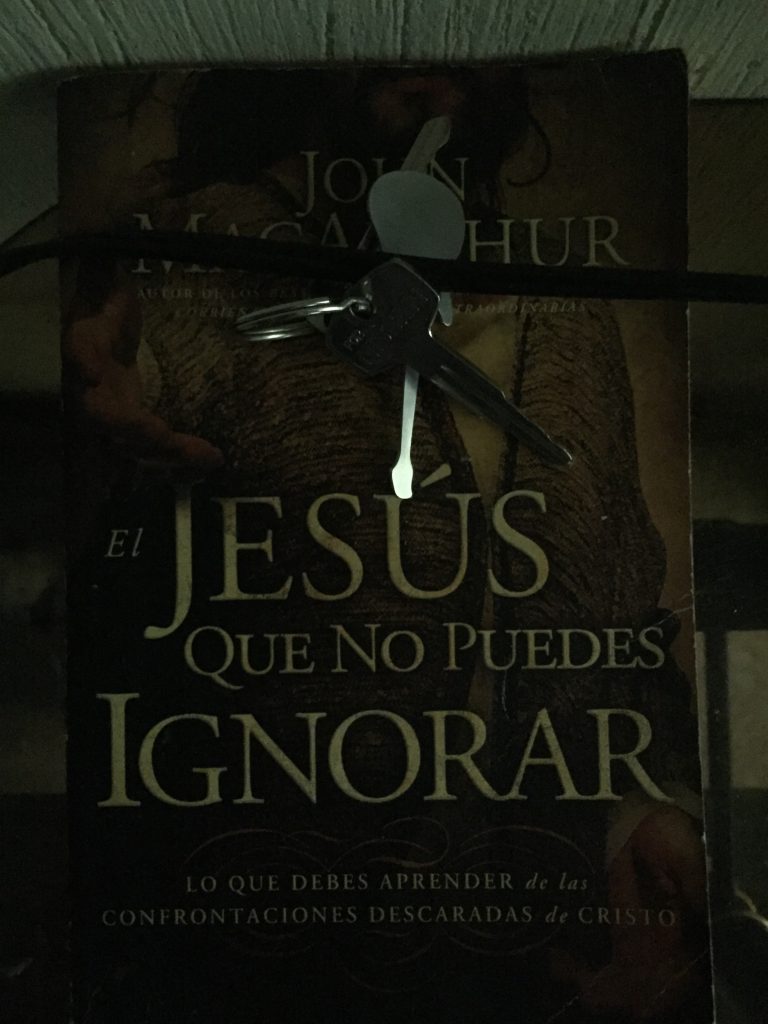

The book on his nightstand is by John MacArthur, El Jesucristo Que No Puedes Ignorar is the title. This type of Protestant literature is no stranger to me or my upbringing and I am relieved that I chose to leave it behind a long time ago. It’s basic and its theories don’t make sense to me and more than anything, I don’t believe it anymore. As much as it would be easier for me to believe it, like it would be easier for this morbidly obese man not to be the size that he is, I can’t go back. I’ve tried several times and it was like wearing an ill-fitting disguise. So what does that mean for me and Broc? I don’t know. There are very few men in this culture who regard women as humans and not as sex objects, or in my case, tall visas. So I don’t think I need to know what anything means about me and Broc, I am just enjoying his company.

I continue to write down more Spanish but now on my phone again: “pulcro” he says. I imagine the word means ‘pretty’ because of ‘pulchritudinous’ but it means neat according to Spanishdict. Close enough. He mentions the word ‘derrumbarse.’ to collapse, cave-in. He says “That is why I love about the Spanish language. A noun, like earthquake, can be changed to a verb referring to yourself. I asked if he’d ever se derrumbó? He said yes.

I am tired and I arrange the pillows to my liking as we watch this man on TV struggle until he dies, just your regular Saturday night romcom. When we are introduced to another large person, oh it’s a Morbidly Obese Marathon, I tell him I don’t want to watch another. He hands me the remote and soon he heads off to sleep. I say: “Where are you going to sleep?” and he says, with all the sincerity in the world, “Con mi Mami.” He’s 38 years old. I’m not in Kansas anymore, Guatemala.

I set my alarm and tossed and turned. This mattress was springy but sunk in and made me miss my own. I am so grateful for my Santa Clara mattress, new and not sink-y when I arrived to site. Now it sinks in a little where my butt goes. Eventually sleep and I came to an agreement until my 8am alarm. I had to be on my best behavior because I was a guest; sleeping in is almost uniformly frowned upon in this country but apparently not by Brócoli who I didn’t see until I was dressed and deodoranted.

I opened the door to the outside world and used the bathroom. Then I prepared to gift the shawl I bought for Doña Francis. I walked up the cement steps with my newspaper and her shawl. As I presented it to her, she thanked me and quickly draped it around herself, smiling. It looked more like a blanket on her small frame. I asked if I could sit in the kitchen and she said: “pase adelante.” I knew she would be preoccupied to serve me breakfast but I did not want her to feel that. I would look up words and wait for Brócoli. I heard the sound of hands tortillaring. I was surprised, I would have guessed that Doña Francis bought her tortillas. Soon she asked me: “Should I serve you breakfast now?” and I assured her I would wait for her son. When I went back downstairs, I saw Brócoli with his eyes adjusting to the world. I was relieved, he struggles with mornings like I do. “Buenos días!” I said. He said something in Spanish and I had already forgotten how fast he talks. I hope he didn’t say something important. He immediately grabbed a broom like the unswept cement was an offense. I never saw anyone sweep cement so assiduously until Guatemala.

I returned upstairs to see Doña Francis with her grinding stone by the plancha, flipping fresh tortillas. It is odd to see a medieval grinding stone next to a washing machine and gas stove. I greet Doña Francis’s Dad, 93, who’s wearing a winter hat like it’s snowing outside. He is eating from a chicken leg accompanied with rice that his daughter served him. “Breakfast food” is just “food” here, in my experience.

Brócoli shows me all the beautiful plants upstairs, he does like flowers. There is a nice table on the other end of the landing ensconced by plants and I say: “How nice that you can sit here and sip your coffee” and before you know it, he’s wiping down the table and fluffing the pillows. Damnit! I did it again! I did not want to sit in this nook with Brócoli like we were on our honeymoon, I was just speaking hypothetically. I returned to the kitchen and asked what a word from the newspaper meant: “desabastecimiento” and he said: “a lack of financial support.” I look it up in my phone: cabal, a shortage.

Soon a sobrina walks in with vegetables from the market, huffing and puffing her way up the steps and presenting the goods to Doña Francisca. A few minutes later, our breakfast is served to us and, on cue, when the tortillas arrive, we eat. I think it was, oh yes, eggs. This time there is an additional plate of fresh cheese which made me very happy. At this time, conversation got real with El Filósofo. I landed on the topic of feminism, a fairly new development for me, and I took a stab at the word not knowing if it was a word: “Feminista”. He didn’t correct me so I am assuming it was right. Conversation led to sexual orientation. I noticed that he whispered the word, homosexual. He called homosexuality ‘inclinaciones‘ and I jumped in: It’s not an inclination, it’s an identity, and to my surprise, he incorporated the word: “identity” and continued.

Our conversation journeyed through the concept of an Absolute Truth and The Bible. I pointed out to him that the Bible says many things, and culture has chosen to interpret it in specific ways. There are some passages that the culture (mine, namely) has rejected, for example “Women should wear their hair long” and chosen to interpret other verses literally. I reminded Brócoli of this when he referred to the Bible’s assertion that marriage be between a man and a woman.

I asked him: “Do you believe it is a sin?” (homosexuality) and this, for me, is bringing out the big guns because I firmly believe it is not a sin. And not in the way many Christians reason: “Well, we all sin so who am I to say…” No, I firmly believe it is not a sin. I’m not even sure sin is more than a social construct but that is another post. And while Brócoli danced around the question with long-winded answers and used phrases like “es complicado,” which I personally think is a way to dismiss responding, after pressed he said: “Ultimately, I am not in agreement with homosexuality.” And while I am disappointed because I do support the LGBTQ+ community, I much preferred him to own up to his opinions on the subject rather than dancing through the same arguments I have heard Christians make a thousand times: “It is not my place to judge other people, etc.” “It’s important not to take the Bible out of context..” It’s frustrating how similar Brócoli’s responses are to the people from back home. It’s a totally different context, but still, John MacArthur and Max Lucado and Rick Warren have made it all the way down here. How did that happen? Even the font on the cover is exactly the same, it’s only the words and the audience (everything else) that are different.

He told me that, recently at his job, he sat-in on a session with a psychologist and a teenage boy (I don’t know how he got permission to do that as he is not a mental health professional but nevertheless) without telling me anyone’s names or personal details, he explained that the young boy expressed that he was struggling and eventually explained that it was because he is gay. I asked Brócoli how he and the psychologist responded, what did they suggest that he do? I was terrified that they told him to pray it away, or seek conversion therapy or stay in the closet his whole life. I told Brócoli this phrase in Spanish “quedar en la guardarropa.” I don’t know if it made sense or if they simply use ‘closet’ in English. Eventually Brócoli told me that they encouraged him to come out to his family, person by person, as he felt close enough with them to reveal this part of his ‘identity’ he said. I was relieved.

Well, that was a light topic for breakfast. I had sipped the nebulous mug of instant, and nibbled on my bread until I made it through the task of drinking instantaneo. I asked Brócoli if we could head into town in search of (more) coffee and we got ready to go. I thanked Doña Francis and we headed out, no pinchirrilo but instead we walked. In 15 minutes we were at Regi’s where I invited Brócoli to coffee. He ordered an Italian soda while I worked on my frappuccino out of a Ball jar and our conversation continued. He recognized some guys in a big group at the next table over, they each eyed me with incertidumbre even as they greeted their cuate. I was uncomfortable with such stares but he did not seem to notice the extra attention.

Our conversation wound from religion to the US’s responsibility and influence in Guatemala and the US global presence. We talked about the indigenous population in Guatemala, how I feel as a woman in this culture and how it has impacted my work. We talked about the US’s intervention in Guatemalan development, if it’s realistic and why it often doesn’t take hold. He had a unique perspective I was interested to learn. I asked him: “Why do male teachers in this society get called “Profe” but female teachers get called “Seño” instead of “Profa”? Shouldn’t it be the same? And he was quiet, “You know I never thought about that before.” At the end of our plática he said: “You know what, out of all the different types of people I have met in my life, I can say this is the first time I have known a feminist.”

He didn’t say it with any disgust or criticism, he was just letting the fact sink in. And I, for one, felt like more of a feminist in that moment than I ever have because, well, it affirmed somehow that I am one. I explained that what I hope for is gender equality but not that women be held in higher regard than men. He agreed, understood. I went to pay the bill and the waiter was confused because the woman was paying. He gave Brócoli back my change, even though I paid, and I pointed it out to Brócoli as we left: “Did you notice how he gave you the money? Because men are responsible for money in this culture?” and he smirked and acknowledged that it was strange.

We walked through the market and I admired all of the traje, rows after stacks. He explained the statue to me: “This was the King of Quiche” and I asked “What about the queen?” and he said: “I’ve never heard about the Queen.” I record a video of all this traje, mystifying, and Brócoli ducks to get out of the frame except I wanted him in it.

We walked back to his house, I got my bags and we made the rounds to family to say goodbye. I met one cousin (the family trickle continued) who just recently moved back from Houston because ‘he doesn’t have papers.’ I listened to his English, reminded that this must be how I sound in Spanish. On the way out, his sister gave me a güipil. What a gesture, what an honor! It’s beautiful and was so generous. Brócoli drove me to the bus terminal in another car. He said: “Creo que Mi Mami está enamorada..” and I asked why, he said: “because she really liked you.” I liked her too. I liked everyone in the family, even Garlic and his tablet, and I do hope I can visit again.

Brócoli told me several times during my visit that he learned a lot from our conversations and that he had a lot to think about. I did too, starting with the Spanish I needed to review. But también I want to remember that I can still enjoy and learn from someone with whom I don’t agree. He was already much more open-minded than many Christians I know. And if it works in my family (our differences), then it can work with friends. It’s uncomfortable, complicado as Brócoli put it, but it’s worth it, right? To know a person. To grow.

With a kiss on the cheek and a big thank you, I was scaling the camioneta “TODOPODEROSO” and headed home.

And that was My Weekend with Brócoli.