“Take a picture of me!” she said and ran close to a Jumping Cholla (which we thought was a Joshua Tree). I didn’t think to shout be super careful; cactus having a way of seeming innocent even though we all know they aren’t. In seconds she had spikes in her skin and an entire bulb of Cholla stuck to her jacket. We pulled the spikes out and shook off the jumping spiky bulb. Deserts are not what they seem.

After our whirlwind tour of the Grand Canyon, Sedona, and a couple long hikes in Tucson, we wound through the Desert Museum banked in the Saguaro National Forest, an entire portrait of earth with towering, glomming, proud Saguaros (pronounced Sue-are-ohs, no ‘g’) shooting up from the rocks like relentless exclamation points. (!) Me and Tanya.

Last week she came to visit. It’s a pandemic, she took a Covid test before and after flying, and we always wore masks. We have to be careful in uncertain times. And still, we reflected that this is the first time our lives have been “normal” in our friendship. Even in shelter-in-place, everything has been calm compared to Peace Corps service. One ride on a camioneta cuts you down to size.

In the face of the pandemic, I needed a friend who hugs, the kind where they wrap you up and the only person they are thinking of is you because you are inside their arms, held close to their chest, maybe close enough to hear their heartbeat, maybe not. Before Amber visited for Fall Break, I had hugged someone three times between June 1 and October 12. I don’t know if nannying counts (though being hugged by a one-year old can be super sweet). Well actually I also had some hugs in Yuma when I visited in July. But I needed company anyhow, and cacti are lousy huggers.

Ever since my first year of teaching started on August 10, I’ve been scrambling to learn how to teach. I didn’t realize how anxious I got before each Zoom class, flinging words into the abyss of gray zoom boxes with white letters to students who I’ve never met in person, or even seen. (I incentivize them with points to turn their cameras on, which works with marginal success).

Over the first two months I limped my way through policies and procedures, lesson plans with learning objectives and outcomes, weeks at a glance and calls home. Then there was fall break. The tension loosened from my shoulders that had been accumulating since I learned 10 different online platforms in 4 days of pre-service. Monday after Fall Break everything felt fine but on Tuesday at 9:30am I burst into tears, like the monsoons that never came this year materialized in my eyeballs. Blindsided, I couldn’t teach class “which is ridiculous” I thought in an empty classroom with a rickety vent “because I am not even teaching.” I couldn’t think straight. I panicked, was panicking, spiraling into tears and entirely, utterly alone on the campus of the high school where I was (am) brand new on staff. The question became: A: who do I call and B: how do I get out of here without anyone seeing me oxidize?

I thought of Aunt Sherri, I thought of Aunt Becky. I thought of Guatemala. I thought of Aunt Sherri’s death in August without her family because that is what she requested. I thought of how Aunt Sherri was the only single woman in my family who I was close to. I thought about how Aunt Sherri is gone and now it is me, the only single, childless woman on my mom’s side. I imagined my own death, alone. I called my sister. I called my supervisor “Tucson Mom.” I called Mom. I called Heather. I texted several others. I got through 4th and 6th period with the camera off and I sobbed, shoulders heaving like heavy wind. I drove to Yuma with no hope but no alternative. I was deeply grateful to have a friend on the other side of the desert.

This is the part where I ask for forgiveness. I ask it from you, my friend, and from myself. Because I’d spent the better part of my service in Guatemala downplaying my struggles with mental health from my 20s. You may even remember reading some of my musings, me trying to make sense of how I had everything I needed in my 20s and still I folded like a cheap suit in the face of- what?- finding myself? The fact is, Guatemala redefined ‘hard work’ and ‘suffering’ in my eyes. I do still maintain that we in the US (in varying degrees) experience a type of privilege that has somehow developed into an angst that encourages our everyday grumbling and apathy. “The line was so long at Publix,” “I sat in traffic for three hours..” when really, anyone facing a crisis knows these things don’t matter. They’re just inconveniences. Until Guatemala, I let those inconveniences convince me that I deserved better. Entitlement is the word I am looking for. How quickly I have fallen back into similar expectations after service: “I don’t get paid enough,” “these copays are exorbitant!” and “I can’t afford that” on rinse and repeat. It’s okay for me not to be able to afford things because A: I have enough and B: I have people I can call if I don’t.

Why did Guatemala change my perspective? Because crisis is more evident there. Far be it for me to paint Guatemala with a single brush stroke as there are plenty of Guatemalans who are not in crisis, but life is more challenging and the metric for what a “good life” is is simply different. I speak as a non-Guatemalan with no authority on the subject and as a white estadounidense (US American) with privilege disproportionate to many other estadounidenses. I am one cactus and cannot speak for the others, but I can describe my viewpoint from my spot in the earth.

After I moved across the country and got the degree I came for, I sat in the empty classroom sponsored by a global pandemic on an innocuous October day and spiraled into a nightmare of negative thoughts like hail on a windshield.

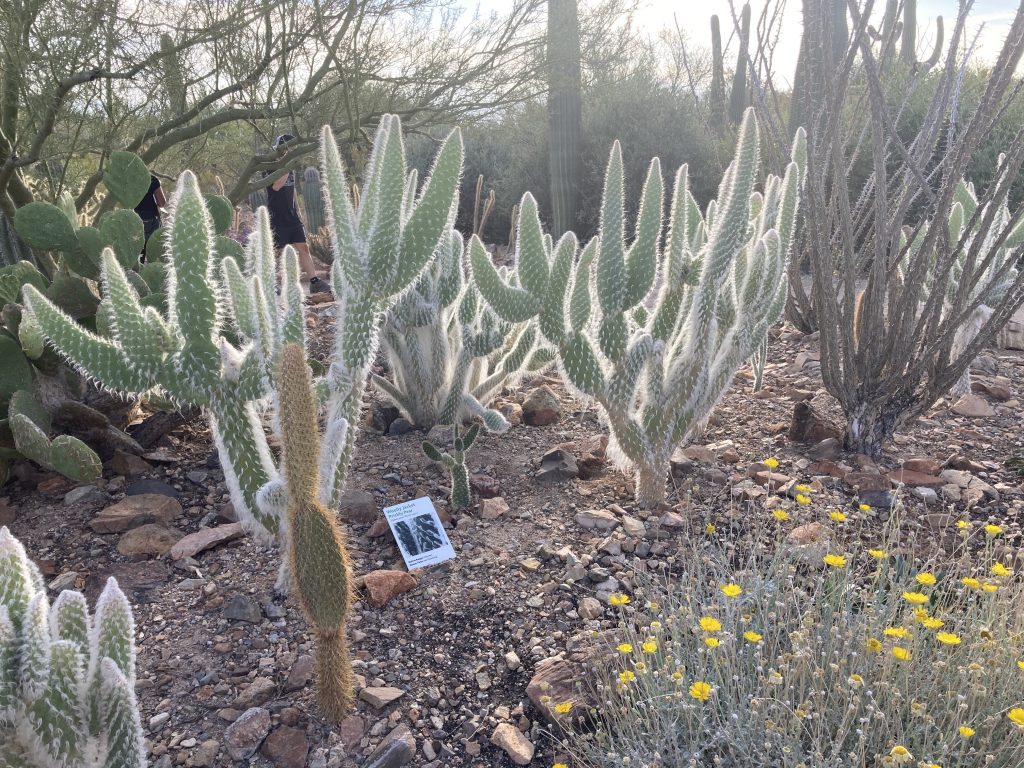

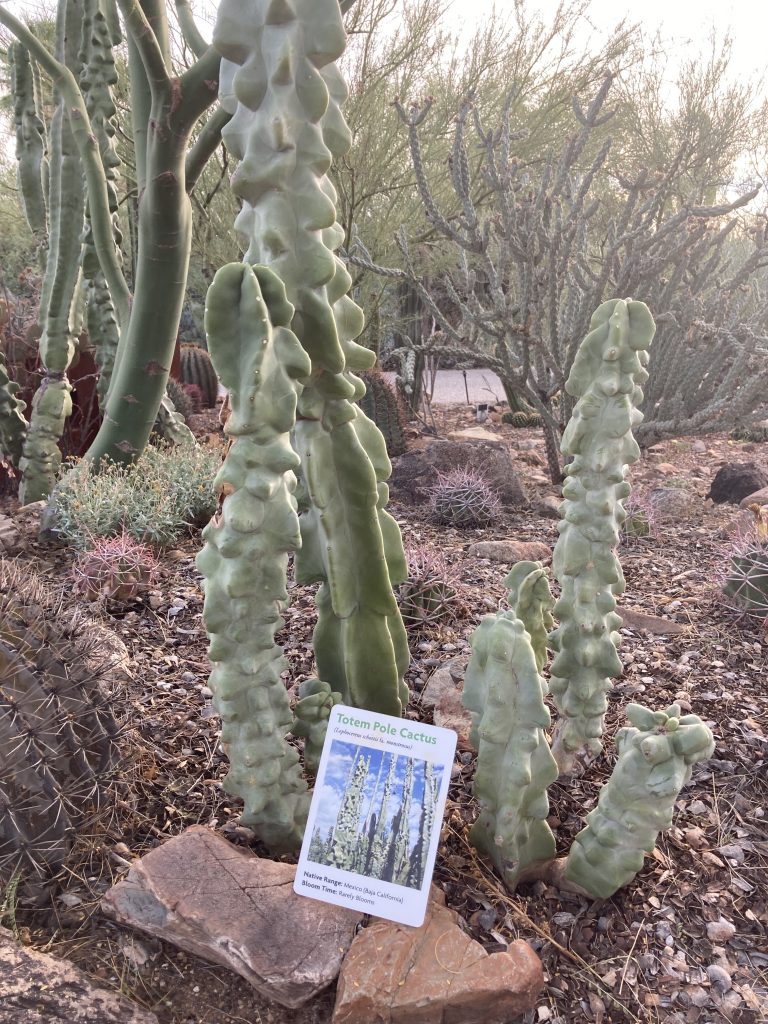

The museum was a bit underwhelming until we saw the sign for the Cactus Garden. This I wanted to see. The placards were scattered among the variations of cacti, each totally unique. We wondered how the cacti got there: plants aren’t like statues you know. We learned about the parts of the cactus: the boot, the spine, the ribs, arms and calluses. A Saguaro can live 100-200 years and grow up to 45 feet (tallest on record, 78 feet tall!) The agave looked painted, some of them, with intricate white lines across their leaves like a single artist went through and spruced them, but it wasn’t so. They came that way. There were a million types of agave and each one was stunning in its own right (apart from the blessing, and curse, of tequila).

“I think healing takes understanding” I mused on the drive from Sedona to Tucson “and that is why it takes so much time.” The road undulated like an ocean on pause, made of asphalt of course. “And if you don’t come around to understanding your pain, then maybe that’s the understanding you find: that you can’t understand.” Tanya acknowledged my thought with a knowing “mmmm” like I found a nugget of wisdom that changed the frame. “Is that fire?” she pointed to a gray cloud staining the perfect sky. “I’m not sure. I don’t think so?” until we heard several sheriffs’ sirens. Soon we arrived to the source: a truck had driven into the guardrail and the whole thing was up in flames. If there had been a person sitting in that truck when it caught fire, they did not survive. It looked like a scene from a horror movie, or a terrible tragedy in a dramatic film. It was the stuff of nightmares.

The cactus we passed were in various phases of life. Some had gray, dying bases, while others were The Grinch green. We mentioned our favorite Rupi Kaur who speaks to the nature of life and death in a garden in The Sun and Her Flowers. Tanya has a tattoo inspired by Rupi Kaur on her arm.

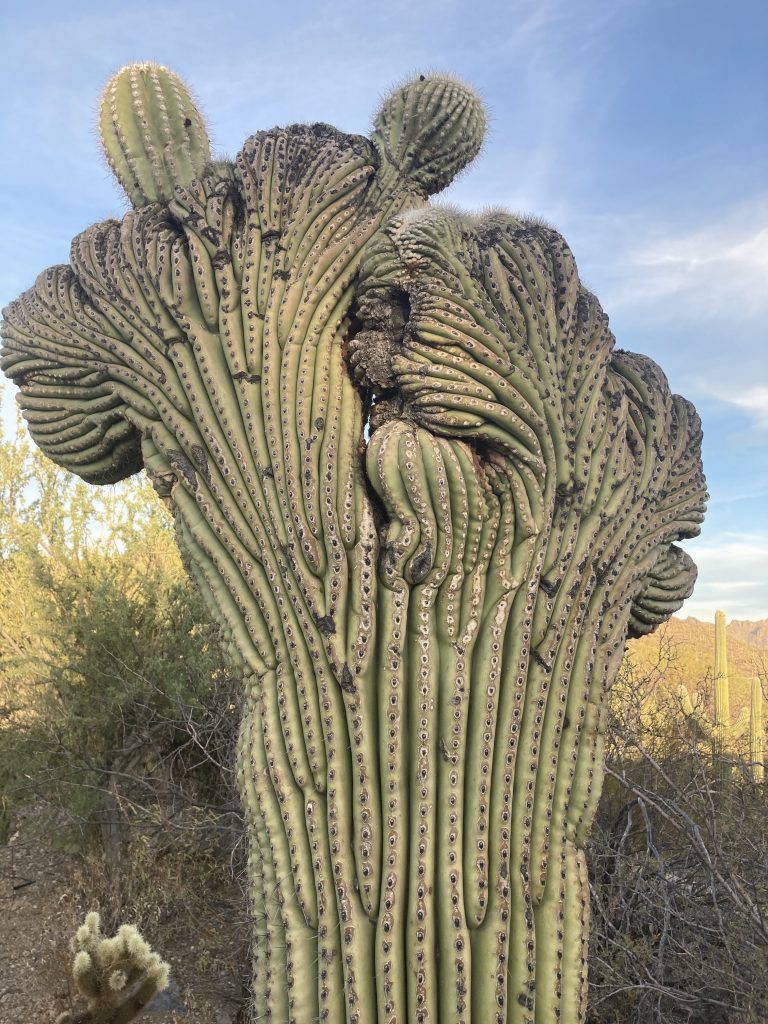

No matter how many times I look at the crested saguaro, or the Grand Canyon or a car accident, I do not and will not understand how such glory and sorrow can coexist. And that will be all that I understand. And I am learning to understand that while I do think our isolation and lifestyle of insular comforts breeds anxiety and depression, I don’t think it makes these realities any easier in the moment(s) we are in them. I think we have lost our sense of community, and with that, ourselves. Even the spikiest cactus is next to another. Even the coyotes at the desert museum were with other coyotes. We are the spines of the saguaro stripped of their green, spiky frames.

I don’t understand cacti, but I know that they bloom these beautiful unexpected flowers as if out of nowhere. Like the plant itself isn’t enough to keep you guessing for all time and then it up and grows flowers. And that leads me to think that flowers wouldn’t be possible without the spikes: if cacti couldn’t defend themselves from predators, they wouldn’t be alive to bloom. And if life wasn’t fragile, it wouldn’t be precious.

So that is how I apologize for doubting the emergent nature of mental health in our nation. Even if I spent 2+ years in a supportive community in Guatemala, I still need community in a place where I am new. And sometimes, when grief, work stress, uncertainty and fear pile up, I cave in too. Saguaros don’t grow to 100 feet overnight.

Deep, rich, real, beautiful…. like you

Another brilliant commentary on life as you know it infused with deep insights on yourself, certainly applicable to any reader who is willing to go there. I so enjoy reading your sensitive and clever and often funny pieces. The photography was stunning. I love cacti, but even a reader who didn’t might love them now.