Animar | 75 Palabras in Guatemala

Amenazas are threats. Whenever I don’t like the way something sounds I just say “Amenazas!” and it’s always worked for me. Like a charm because I like making people laugh and the translation of the word “threats” lands how I want it to. There are a lot of words that just don’t have the effect I’m aiming for in context. By example, the word ‘abusive’ is a serious term in the States, but people here say “abusivo/a” jokingly. The girls who work in the library aways call me “amiga abusiva” to goad me and get my attention. That took some getting used to. Now I understand it’s meant to be funny but at first I was like: Hold up.

But I say “Amenazas!” for comic relief. “I’m going to be fluent in K’iche’ when I leave” “Amenazas!” or if a Guatemalan says something to joke with me I respond “Amenazas!” Or if my host family says “Natalie’s going to wake up at 6:15am to go to the molina with me” I would deflect with “Amenazas!”

And when I arrived in Paquip by way of tuc tuc on Thursday March 23 I sat in la dirección fumbling around as usual, looking for pens and pretending to be productive (to myself and everyone else). Y’see, I was supposed to give an identity charla at 1:25pm but it was rescheduled because that’s how it usually happens. Your plans- you can expect them to go as unplanned. In my hour to spare, in walks Profe Alex, great guy, who asks the director if he can go visit “Sula” to ‘animar’ because he heard the students mention that she is sick and hasn’t been in class. I’ve also noticed her missing. The Director explains: “Yes, I called her mother and was informed that there is something going on with her nerves and her brain and she is not healthy enough to attend school.” I sit, I fumble about but my ears are piqued. By the end of the exchange, Profe Alex has gotten permission to visit Sula. I offer to watch the class while he’s gone. But through the usual unwrinkling of details via repeating the same questions, I’ve misunderstood that Profe Alex is not leaving the class to go visit her, he is taking the whole class with him to visit Heidy. Now. Did you think her name was Sula? But then I just said Heidy? Welcome to my life where everyone has two first names except you. You can’t accuse EstadoUnidenses of not being brief.

And in a matter of moments 2 adults and 23 bushy-tailed adolescents are walking uphill on the symmetrically arranged pavers of Paquip. Me, Profe Alex and a bunch of 6th graders have taken to the streets in search of I’m-not-sure. I take a few selfies with the students while donning my mint-colored sunglasses. Boys and girls are always in separate packs and I end up walking with the girls. “Il q’aq!” or “It’s hot!” I exclaim in K’iche’ as we venture under the Guatemalan sun. Of course I pronounce it wrong. The girls ask if they can borrow my sunglasses and that they’re going to break them, to which I say “Amenazas!” They repeat “amenazas!” to each other in giggles like a melodic hook. I’m not sure why it’s worth repeating except whatever I say is simultaneously odd to them and worth repeating always.

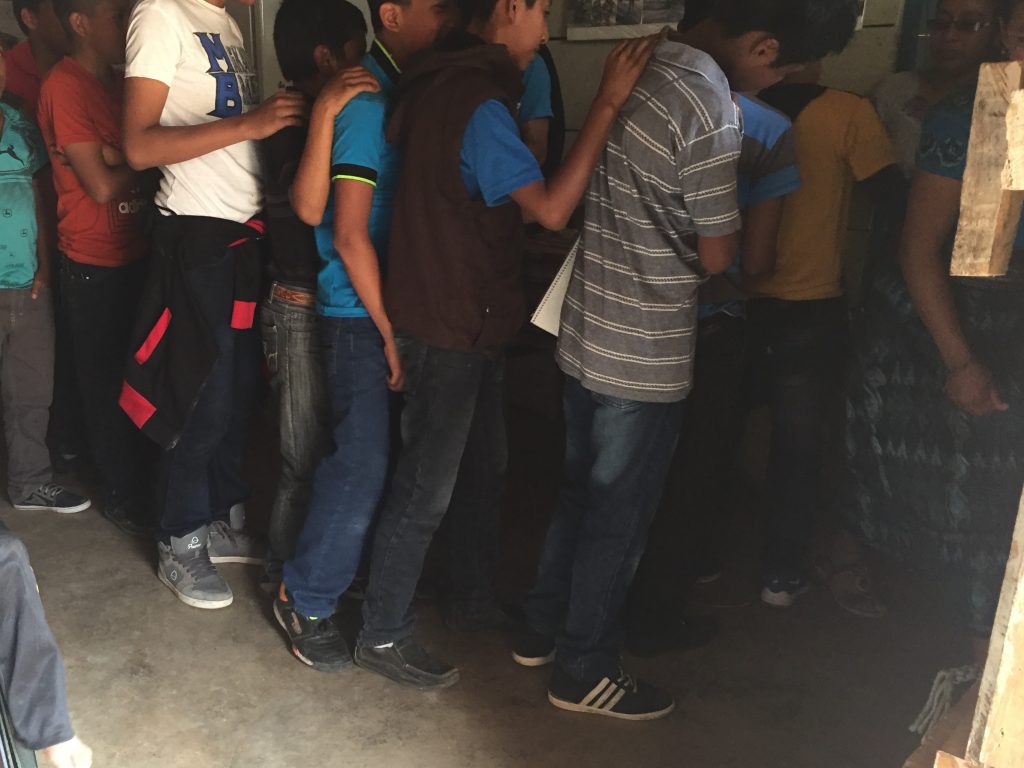

I hear Profe Alex say “Muy Buenas Tardes” and I see that we’ve arrived in front of a humble home with a pile of brush burning out front. A woman stands by the front door. You know that moment in a Western when the main character gets to where they’re going and the audience sees the guest come out of the house? And everyone waits to see how that person from the house will respond? It was like that. Is the mom happy we are here? Annoyed? Mad? Bombarded? The students seem to arrange themselves around Profe Alex as they peer in with him at the helm. There is quiet. He explains respectfully that we have come to visit Heidy/Sula and to see how she is doing. I see sweet Heidy’s head peek out from behind her mother. Heidy’s mom explains that “we’ve just come back from el monte” and please “come in.” And before you know it we are all piled into this 3-bedroom house in the kitchen.

I didn’t know that inviting myself on this house visit would put me in the middle of a heart-clenching exchange. But it was also almost too quaint, too sincere and too beautiful to be real. Almost like waking up in the house that was made out of a shoe. You know that fairy tale? Why would ANYONE want to live in a shoe of all places? But I felt like I entered a parallel universe where people are more important than phone calls, family meals more important than Facebook and the fate of one student more important than a class lecture.

The boys lined one wall, Profe Alex leaned up against a cabinet, and the girls inhabited the adjacent wall. I propped myself just outside the front door, not feeling totally comfortable to enter. This was all normal enough to everyone but me. But I did not let that show. I simply observed and was. I listened to the crafted words of Profe Alex, explaining the reason for our visit. “First of all, Muy Buenas Tardes Seño, Sula. Estamos aqui con Primero Basico para visitar a Sula. We are here to encourage Heidy/Sula and to say that we’ve noticed she hasn’t been in our class.We want to thank God for this opportunity because we know that God knows what we don’t understand.” At this point her sweet face is peering out from behind the curtain from the adjacent room. He has a traditional series of words of welcome because Guatemalans can sculpt a speech on the spot and I’m always left spellbound. But this is the cliff notes of the greeting.

Profe Alex leaves a space for the host mom to respond. She says “Profe. First of all, Buenas Tardes a cada uno de ustedes. I want to thank you for coming today. My daughter has struggled in the past when going to school. And sometimes I am not sure what happens but I always tell her “Do not pay attention!” but still she suffers.” (I am taking this to mean bullying, but I’m not sure). “But this year, when she returned to school, she fell ill and had to go to the doctor. He told her that she is having problems with her brain and her nerves and that she cannot return to school.” She begins to fight tears “The doctor says that she must rest, that she will not be well if she goes to school. So no Profe, she cannot go back. You ask if this is a possibility? Well I have to say that no, it simply isn’t. So Profe, I’m sorry but I simply cannot send her back to school. And my husband is in ‘otro país..’ (which I assume is the US- but why doesn’t she say US? is it because I’m there?) and these medical tests would be very expensive and so she simply can’t go back to school.” And the details persist: why life is hard, why her return is not possible.

I remember the words of my host mom when she said: “Me cuesta” about speaking Spanish. At the time I didn’t understand, her Spanish seemed natural and easy to understand. But little by little I’ve seen the ways the pronunciation is hard for her, or how she can’t remember the terms for things in “Castilla,” and I understand. “Me cuesta.” And I think Heidy will someday say “Mi salud me cuesta.” And it will cost her. It will cost her a profession in place of work, a future in place of living, a reality in exchange for a life. But I thought Heidy/Sula looked like she had a different kind of future when I first saw her face on the lefthand side of her classroom, her face honest and kind and calm, more mature than the others, listening and responding and dissolving the concepts.

I look at Profe Alex to guide us. He looks burdened and I think I hear words catching in his throat. I’m not sure if it’s him who’s sniffling or a student or many. And then I look at Sula. Profe Alex has the hard job of responding to this news, but for him it’s only news. For Sula it’s her new life. How can he comfort her when the answer is a solid, hard-fast no? And her house is in walking distance from the school. Can’t she just phone in, then? Do her homework and bring it in separately? Or sit outside the classroom and listen? Or I can bring her her homework? Or can she just rest for a few weeks? Sula being 15 and in primero basico/6th grade does not show promise for her to graduate, ever, from middle school. Forget high school, forget going to university. She will be a daughter who helps her mom at home with sweeping and tortillaing until a man marries her and she sweeps that house and tortillas for him and has babies who she ties to her back as she walks to market or washes clothes in the pila. And I’ve seen it enough to know what the future will be.

I want a different future for her but I can’t change it. And neither can Profe Alex. So he says in more or less words (because I can’t begin to retrace his delicate verbal steps): “This isn’t goodbye, this is just a time for us to all offer our encouragement to Heidy/Sula and to give her our warmest regards. We understand the difficulty of this situation and we know that only God knows. And how difficult when something like this occurs in someones health because only God knows. Only God knows.” These are the exact situations that make me question the character of this God. If God knows, why doesn’t he intervene? If he is God, and God knows, why doesn’t he help Sula?

I hear the words of Profe Alex and I know it’s my turn to give words. Giving words has become easier through the months, but it’s still a foreign concept. I think I’m doing well and saying things as delicately as I can until I heard the word “simpatía” and I hear an eruption of giggles. I’m used to them laughing at me but I’m casi casi segura that simpatía is a real word. I conclude and a student Juana gives words of encouragement, and then like clockwork we all line up in a winding line and one by one dispense hugs to Sula. I see that she is crying and grasping some students with a firm grip as she cries. How must this feel for her? Goodbye to her friends, her activities, and her future in a series of hugs? The boys, as awkward as they are, still take it seriously enough to give her a real hug without giggling profusely that they had to hug a girl.

And I am second to last and grasp her tightly, I hug her as she cries into my chest. I don’t know her but I feel like I do: I think I understand her delicate spirit and her dreams. And I feel them dispel as her tears fall. I say that she is special, that everything will work out and that I will come visit. I can promise two of the three things I said.

And I did come visit, that wasn’t just a threat. I splurged on the Q39 sized Faber-Castel pencil set and printed off four coloring pages from the library. When I got there three days later, she had fully adorned the beautiful face of one of the drawings. I saw her creativity, her patience and her diligence in patterns. I sat with her mom, Heidy and her youngest brother Felizito. I had to fight the urge to leave after 30 minutes of coloring. I don’t know why but I felt like 30 was what I should give as I was just “dropping in on the way home from work.” But I stuck it out for an hour and I hate that I even had to “stick it out” given the situation. In the midst of my imperfection there are some things you should stay until 5pm for, and some things you should spend more q on, and I knew that when I saw how much progress she had made with the colors.

Ánimo, Sula. Ánimo.