Continuing, my parents visit, the first post here.

DAY FOUR:

In the morning on Thursday, March 29th, I woke up on fabulously comfortable mattress in Antigua to find my parents had already eaten breakfast. Hostel included breakfast, though they should have sung and dance as they served the food for how expensive the place was. I got my fruit, yogurt, granola and strong coffee, and then brushed my teeth and packed up all my stuff. While my parents were anticipating seeing Santa Clara and what they’d imagined about my home for over a year, I was sad to leave the shabby-chic corner coffee shops and transience of Antigua. So we got a taxi (tried Über but neither the internet nor TiGo service was working), so the hostel guy made an old-fashioned phone call to a taxi and we kissed Maya Papaya goodbye.

We took the winding drive upward to Santa Lucía Milpas Altas, a small town outside of Antigua where the Peace Corps Office is located, and we ran to the centro comercial across the street, ordered sandwiches (saying tenemos prisa) because if you don’t tell them you are in a hurry, forget it) and crossed the busy street back to the office to quickly sit, eat and board the shuttle. They didn’t get to see the inside of the office which was a bummer (closed for Semana Santa) but they got a feeling a little. They didn’t know what they’re missing, the courtyard inside is dripping in hydrangeas.

You cannot be late for the Peace Corps shuttle or you get left. The Peace Corps Shuttle driver, Carlos, was very kind to my parents. He said: “Please tell your parents that if they need to stop to use the bathroom for any reason, to please inform us.” This is not something the shuttle ever says as they follow the strict schedule and only stop in the pre-determined spots. I felt the respect that Carlos showed for my parents and remembered that this culture has an inherent respect for elders and parents that way. I translated what he said, thanked him and we left the office and started our 4-hour journey, riding the hill back down where we just came from. The shuttle wasn’t stopping in Antigua like normal because of all of the processions, but I didn’t see any processions, which means we could have had a relaxing morning in Antigua instead of looking for a taxi, but alas.

My parents had taken half of a dramamine each because the drive can be unfriendly to carsick-prone people. Thankfully no one got sick. My dad rested but my mom and I mostly sat up, looking at the quiet country pass by with the stops and starts of the manual transmission. I didn’t sleep, I just watched the familiar countryside pass by, windy and hilly and green. In 4 hours we would get to Santa Clara. I was anxious about being dropped at Km 148, my shuttle stop, because finding seats on the buses to Santa Clara can be difficult, but early in the afternoon there should be space.

We took a bathroom break at Los Encuentros like always and my mom bought two dolls from a sidewalk vendor, recuerdos of Guatemala. I was excited because they were a good price ($2 USD). Where their visit would end (Panajachel) everything would be triple the price. In another 30 minutes when we got to KM 148, my shuttle stop, our time on the comfortable, private, quiet, calm Peace Corps shuttle ended. We took our bags from Don Carlos, said goodbye, and walked down the hill to the stop where there was a Santa Clara bus already waiting. When I see that bus I am home. It’s more than one bus, it’s several, but when I see any bus going to Santa Clara, the ayudantes and (some of the) drivers know me. They speak to me in K’iche’, yell out my nickname (Pawapik’ a wi) and exchange our usual banter.

The ayudante helped briskly load our bags up top of the bus. We took our seats and my parents got to experience a bit of my K’iche’ personality (they say your personality changes with every language you speak. I think my personality in K’iche’ is CLOWN). The bus waits at this stop so it can get more passengers. When it fills up again, we go. I yelled out of the window “Jo Jo Jo pa wachoch….” Let’s goooooo to my house. The people on the bus who didn’t know me were quietly surprised and laughed at my K’iche’, though most people acted like they already expected it. The others were chuckling and asking me the usual questions, which I can only half understand in K’iche.’ Jawi kat spewi? Where are you coming from? “Janipa junap..” how old are you? and etc. I also tell them I’m not married: “Maj wachajil” (no spouse). And they always think it’s the funniest thing. Hmmm.

The clouds set in on the ride through what would be tall milpas except all the crops haven’t started to grow. The corn wouldn’t start really growing until the rain set back in (May-ish). We wove through the roads and, while my parents had no idea where we were, this route was totally rote to me: my gateway to the outside world. I knew every twist and turn and the stops and the spot where the ayudante asks for the pasaje/bus pay. I bet their eyes were adjusting to seeing traje típico on most every woman (whereas in Antigua only the people selling on the street are in traje, whereas almost everyone woman here is in traje). We passed all the large blue signs in caps: San Juan La Laguna, Santa Clara La Laguna, San Pedro La Laguna, San Marcos La Laguna, Santa Lucía Utatlán and Santa María Visitación. One name for each sign, stacked on top of each other and overwhelming the post they are attached to. I don’t know why they didn’t make one sign with all of the names on it…

Santa Clara is at the top of the mountain on the way to a lot of other sites on the lake. Each name, each place, means something different to me, but to an outsider they are a bunch of Spanish saint names that all sound the same because they end in “La Laguna.” We wound through Tierra Linda, a sort of half-way point for the trip, up through the windy incline to Santa Clara and the beautiful green all around, even though it’s not nearly as green as it is other times of year, it’s still ‘eternal spring.’ When we passed Santa María Visitación, the sign bigger than life, I told my parents we were almost there and they readied themselves for the decline. When the bus dropped us off next to my house, we got our bags thrown down by the ayudante from overtop, and they followed me the ten paces to the side door, pushing the swinging corrugated steel/lamina that is the side door that we tie up with a rope, and I said: “Here’s my house!” The moment I’d only been planning for since we booked the flights and imagining since long before.

The door swung open to reveal Abuelita walking towards us with a big smile, and Clara and my host mom immediately following her to meet and greet my parents. We were standing in the patio area where my host family does everything: weave, clean the kernels of mazorca, organize their threads into colors and patterns one after the other, hang their laundry to dry, clean the herbs my host mom sells to her neighbors and then washes her feet after a long day in the field. It’s where almost all of the work happens in the house.

I hugged my host mom and I could feel the happiness and anticipation in her embrace because we don’t hug unless it’s because I’m returning from something. Usually we do the cordial kiss on the cheek. I presented everyone to my parents and my parents to my three host family ladies, a kiss on each cheek to my parents and vice versa, menos Abuelita who doesn’t do the cheek-kissing routine, and I translated what my host family had to say. “Que sea bienvenida en la caaaasa. Mucho gusto en conoceeerle. Ésta es la casa de Nataaaalia.” And they helped us carry our bags upstairs. Upstairs is just my room, bathroom and the pila (the cement sink where I wash my clothes, dishes..) I unearthed my key from my purse and pushed the metal door open to my two-room place. My dad went for the windows and balcony standing with arms clasped loosely behind his back as he took in the view, while my mom took note of the interior, my hammock, my pictures and noting the details of the traje hanging on the walls. I showed them my second room, my bedroom, I got emotional. “I can’t believe my parents are in my home!” My mom was right to my side to squeeze my arm. They both smiled and I think my dad’s eyes welled up. It was emotional, your parents coming to a place so special to you and so different, a place you call home.

They told me how nice my apartment was, how comfortable and how big. It reminded me how lucky I was for so much space. I got really double-lucky with my host family and my home. It was like the fates knew how important my home is to me and how much my surroundings can impact me.

Like that, my parents had a visual reference for my day-to-day life. It wasn’t before long that my host sister brought up a mango drink, a blended mango in water (real delicious). We sipped and my host family told us to come down for dinner when we were ready (it was only 5pm). I showed my parents how the bathroom works, how to open and close the doors (pull on the string and it moves the latch which opens the door) and how to wash their hands (you use this shallow bucket to take water from the center basin of the pila and you splash the water over your hands over this side of the pila so it goes down the drain). You spit here when you brush your teeth, remember to still use your bottled water for that.

Soon we went down for dinner and I was a bit anxious because I knew my host family would notice everything my parents did and did not eat. We entered the kitchen where I spend almost 2 hours every day, preparing my lunch and dinner on one of the wooden cutting boards and using the same pink teflon pan every meal to sauté potatoes, or cooking eggplant directly on the iron stove surface. The three of us sat around the kitchen table which hardly anyone uses and my host family sat around the plancha. Normally the four of us (Clara, Rosario, Clarita y yo) sit around the plancha, the wood-burning stove, and we only use the table to prepare the food.

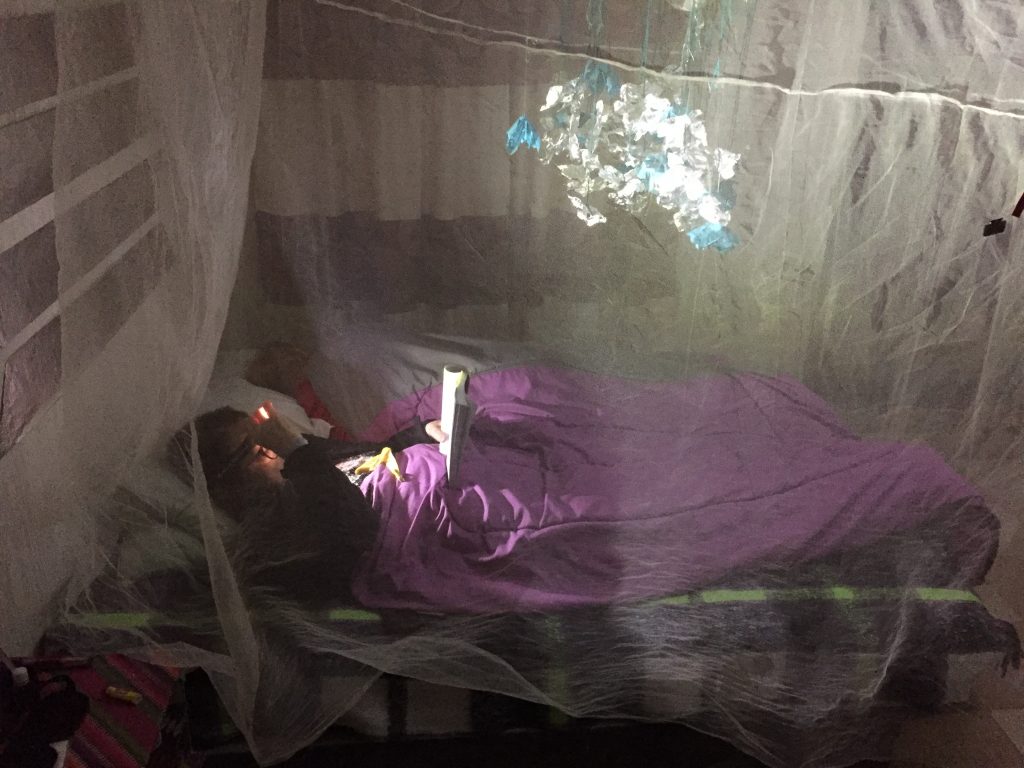

The chicken was a bit dry because they had prepared it at lunch and reheated it for us for dinner. My dad whispered: “Natalie, is there any sauce I can put on this?” a question I was waiting for and I responded: “No.. sorry.” I put picante sauce on all of my food but my dad doesn’t like anything remotely spicy. I encouraged them to take more tortillas, per my host family, but I know my mom and dad were thinking “carbs, carbs, carbs.” After we finished, I prompted my parents to say “Muchas Gracias” to which my host family replied “Buen Provecho.” We went upstairs and not long after that my parents were asleep. I could hear their measured breathing, and sometimes my mom’s snores, from the floor in the other room where I laid across my colchón, a padded mattress that I bought from a traveling truck salesmen. Out first night in Santa Clara but we hadn’t seen Santa Clara yet. I went out to refresh our supply of agua pura, and we all went to bed, my parents under my bed with mosquitero.

DAY FIVE:

In the morning, I slept in as late as I could justify (8:30?) and lifted myself up off the colchón. I heard my dad speaking in English to my host mom downstairs (sigh). It was pretty hilarious to overhear because she did not understand, but he continued anyway. I began to make pancakes with platanos/plantains and coffee for my mom and I. They sell pancake mix in boxes at the local store, thank goodness. It’s good for hosting though I hardly ever make them myself. Normally I only make my coffee on my small stove upstairs, so cooking in my little area was awkward for space and the utensils I kept going downstairs to borrow. While I made the pancakes my parents stepped outside to see the alfombras which were already in full effect. They walked all the way around the block to see them. The alfombras are elaborate carpets made out of flowers, pine and dyed wood-shavings and they are to honor the path Jesus’ takes from his crucifixion to his tomb on Good Friday. The townsfolk carry Jesus over their shoulders, his figure crucified, and in doing this all of the designs are mixed together and destroyed by the foot traffic. Each family gets a section of the street and they spend the hours of the early morning drawing chalk on the sidewalk as a guide, then using stencils to slowly dust the dyed wood shavings in beautiful patterns of flowers, birds or other designs.

It took me about 30 minutes to make my pancakes and plantains, after which we sat and ate pancakes with honey (most folks here use honey on pancakes instead of syrup). I told my parents it was better that they went around town the first time without me. If I had been with them, we would have had to stop to make introductions to every which person passing us or we would be rude not to. En fin, they got to see Santa Clara somewhat anonymously which is much faster and easier. Thought everyone probably assumed they were my parents, who else would be walking around town like that who looks just like me? Plus I had mentioned to several people that they would be coming.

When we finished breakfast we braved the outdoors to find our spot for procession-watching. We did a few introductions, my parents not understanding the Spanish I was saying, and me explaining to everyone “Ellos no hablan español…” This surprised folks because families are always so directly linked here. It doesn’t make sense to them that I would speak it but my parents not be able to speak it. Even though, many grandparents here don’t speak Spanish and their bilingual children and grandchildren (K’iche’ and Spanish) only speak to them in K’iche’.

And I ran around with both of my cameras, polaroid and cell phone, trying to capture the beauty of this beautiful alfombra before it would be walked across. We walked down to Barrio San Antonio, a different neighborhood in Santa Clara, where my school is located. They got to see the basketball court and the building where the classrooms are located. I explained that the elementary and middle school share the building, that elementary school is in the morning and middle school is in the afternoons. I don’t think seeing the building helps understand what being at the school is like, seeing as this took me almost a year to fully understand (and I’m still learning), but it was still cool to have my parents where one of my work assignments is.

After our walk down and back from the school, we came back upstairs and my dad rested while my mom and I went to bring little gifts to the neighbors. Gift-giving like that can be difficult because you can’t show up with a bag of gifts and expect people to distribute them amongst themselves when you are gone. You are supposed to present each individual with each gift, which can be difficult because families here are so large. And you can’t say: Share this box of colored pencils. They want to know whose is whose. You try to do a nice thing and you ended up causing more of a mess than anything else.

For lunch, we went to the plaza and I explained the comedor food to them (we can do beans with this weird version of Chao Mein with güiskil, squash, and carrots cut up into it, or fried chicken, red meat but I wouldn’t suggest it… or which sounds good to you?). I think my dad went with the safer spaghetti and my mom and I the chao mein. It’s honestly the humblest little hole-in-the-wall but with the three of us, I was surprised by how much money I was spending on everything. I called Gloria “are we still coming for lunch tomorrow?” and she confirmed that we should come.

My dad wanted to do a “Happy Hour,” his words, in spite of my email advisory that it’s difficult for me to buy alcohol in site; there’s a stigma around it in certain communities and many of the men here drink to excess and physically abuse their wives. But I wanted a beer myself so we walked down to the corner store and bought three coronas and some beer snacks, peanuts and such. I told the store attendant that my dad was going to drink them all just to cover my bases (I told him later he said “Good!”).

My dad said: “Natalie you can’t have a conversation with anybody around here.” He was referring to the fact that no one spoke English, or that he didn’t speak Spanish. I told him I would translate for him if he wanted to chat with anyone. We went downstairs to the kitchen where two host cousins were visiting abuelita. I explained that my dad wanted to chat and if it was okay for me to translate (at this point, Mom was upstairs resting). And so my dad, as a protestant minister, naturally asked first: “Do you go to church?” Not knowing the discomfort between Catholic and Evangelical Christianity in this culture. As it would happen, my host cousins are very evangelical and my host family (Grandmother, Mom and Sister) are very much Catholic. After several questions and answers and the silence I felt from my host mom and sister I asked my dad, can we change the subject? Next up: SPORTS (I think my dad’s conversational topics tend to be Church, Sports, Politics, none of which I engage with very much, especially with the state of affairs in the US currently). I love my dad and we are so, so different. My dad brought down peanuts and as he unshelled them and offered them to the host family, I unshelled his words into Spanish.

I cooked eggplant, potatoes, tomatoes, bell peppers and onions with noodles for dinner in my kitchen upstairs. I had given my host mom 50q and asked her to go to the market and buy a bunch of ingredients for me. Market day is Tuesday and Saturday and I knew I would need groceries for Thursday, Friday and Saturday. I made her a list, but she doesn’t read, so I think my host sister had to read it off to her a few times before she went down to the market. I pictured her carrying all of my groceries back to the house, uphill, in a basket on her head. For dinner I borrowed some tortillas from my family downstairs, which I think my mom and dad ate one and a half of, and I think we were all tired. Culture shock is tiring, translating is tiring. Walking all the time when you are not used to it can also be tiring. Saturday morning, I got up, made eggs and called the hotel in Pana to ask if we could come a night early. I think we were all a little bored in Santa Clara, as beautiful as it was, and we would be ready to leave the next day.

DAY SIX:

For breakfast, I made eggs with tomato and onion and coffee for my mom and I. I washed all of the dishes and hand-washed my laundry, too. Then we got dressed and ready to go to lunch with Profe Noel’s family. Before we arrived to their house, we walked through the market. The plaza is literally the center of town life, and I was disappointed that the Saturday market wasn’t nearly as full or vibrant as it usually is. Normally, I can’t see most of the sidewalk because it is covered in vendors and there is a ton of foot traffic. I tried to explain this to my parents but I don’t think it mattered to them like it mattered to me. They said: “Well, we have an idea..” but it’s not the same. You have to survive a market day to know a market day.

We walked back through the quiet-ish market day and headed to lunch.

The backstory on Profe Noel is that he is a very cute, very adorable physical education teacher. He is not my height, but when he stands on the curb we are almost the same height. He has all of his teeth, and they are his natural teeth, and none of them are rotting or broken, so he is already the PICK OF THE BUNCH (I am being so facetious when I say that, but it is also very rare..). So I started telling people I had a crush on Profe Noel sometime last year and one day I busted into his house thinking he wasn’t home (because that’s what my students had told me). Turns out, the man was home. And I stood there awkwardly and told him he was cute and that I had to go.

At this point in service, I go to visit his house and his family once every one or two weeks. We all joke about how I am going to marry Profe Noel. They say: You need to go into the Tuj with him (that is their sauna/bathing room). And I always say: But what if I don’t know what to do with the things?! (Referring to certain body parts; My personality in Spanish: funny. My personality in English, TBD.). So Profe Noel’s parents, without realizing it, pulled a fast one on my parents. Naturally my parents saw their humble home, dirt floors in the kitchen area, plastic sheets on the ceiling, and sat on the bed fashioned out of wooden slats or maybe plastic crates, I’m not sure, and maybe they wondered if his parents really did want Profe Noel to marry me and come to the States so he could have a better life.. I can’t blame them for that. But Profe Noel’s family has more than a comfortable home, they have each other.

Profe Noel’s family was all dressed up. They lined up in the main room of the house to greet us like the children in the Sound of Music and Gloria gave us a formal Bienvenida. It was Sábado de Gloria (or Sábado Gloria, TBH I don’t know) which is the Saturday after Good Friday and before Easter Sunday, and they had a church event after our lunch. However in the moment I was so surprised by how dressed up they were for lunch. Doña Celia and Don Francisco have 7 children, 6 of which were seated with us at the table missing Gladys who “left with some friends” which I chided them about.

This family is so interesting to me: each child has such a different personality. Estela is the oldest and she is like the mini-version of her mother, she looks older and more tired than all her other siblings maybe for being in charge for so long. Gloria is next, the breadwinner of sorts. She has an office job in the town hall and she also helps sell the bread, the family business. She wears glasses and looks studious. After is Amadeus who everyone calls ‘Yito. He also works for the muni but in maintenance, like painting and such. Después follows Profe Noel, the beautiful physical education teacher with a bright smile, Teresa the designated cook for the family because she isn’t working or studying, Gladys, a shy tomboy, and the baby Wilson the Smiler. He smiles at literally everything.

Be the home of Profe Noel simple and humble, a sense of humor is dignity. And his family loves to laugh. His mom, Doña Celia (my mom’s name being Cecilia, go figure) kept asking me to ask my parents: “So, what do you think of Noel? Do you want Natalie to marry him?” And I was funnily in the middle of this transaction of words, Noel sitting on our end of the table and laughing at everything his mom said. I think my parents were trying to figure out the norms of being invited to lunch, another tortilla here, squeeze lime sauce on the cucumbers, take salt with fingers from the pile in the bowl, and laugh at all the right moments and ask questions at other moments, and between the tug and pull of all of these societal differences, they were just doing their best to eat the chicken. My dad said: “this chicken is really good.” And I made sure to tell Gloria “My dad loves this chicken.”

When we finished lunch, we thanked them so much for the food and they showed us the tradition of coyol. I don’t know how it is spelled but it’s a round fruit that you cover in warm molasses. We all tried the molasses, sipping it, not understanding that you were actually meant to insert the round coyol in your mouth and slowly work on getting the fruit off of the pit. But we didn’t know so they probably just thought we didn’t like coyol but really we just didn’t know it was edible.

We sat and watched the soccer game, Real Madrid vs. Barcelona, and my mom and I were excited but Dad didn’t seem so whelmed. We left with a big thank you, hugs to everyone, some small recuerdos as gifts from the US and a group photo. Of course they made Noel stand next to me since our fictitious union was the cause of such a lunch.

When we walked out my parents said: “I think you need to be careful..” and I told them not to worry because Doña Celia knows I don’t want babies and she very much wants Noel to give her grandchildren, no importa that she has 6 more children who could produce babies. We walked home and prepared to hike the Mayan Nose. I told my parents to take their time and not feel rushed if I was ahead. I walk up hills every single day and I’m sure I’m used to the altitude. I kept asking them to gawk over the view(s), but I think they were a little winded. When we got to the first lookout, we took all of the normal photos of ourselves posing just by the water. One of the guys who maintains the grounds took photos for us, and while my mom was dubious, I convinced them that the next lookout had an even better view.

When we got to the very top, I was pleased with the view. We could see the lake in all it’s glory even though it wasn’t as clear as some days, it was still clear enough to be beautiful. The whole lake is a stunning vista, it’s gigantic for one and it’s planted in between several mountains and volcanos. Everywhere you look is either green or blue. (It’s called the Nose because from below, it looks like the face of someone laying down, looking up).

We passed my friend Claudia’s house, and to her great shock, I introduced her to my parents and we drank coffee and bread (I explained that, I am so sorry, but my dad doesn’t drink coffee) and I hope they weren’t offended. We got a sweet picture at the end and my parents always ask me about Claudia still. I gave Claudia this picture 🙂

When we walked down the nose it was probably 5pm, Dad and I arranged another “Happy Hour” and I think we ate out at another corner eatery (but honestly I don’t recall). Nope, I remember I bought my favorite, pureed beans from the corner shop of the 4 sisters from Sololá. They didn’t believe me about how delicious it was until they tried it themselves and my dad said he wanted more. After dinner my dad really wanted to see March Madness so he found a cevichería to watch the game. He asked me for 10q to pay to watch the game. When he gave Manuela the money she said to me: “Somos cine?” “Are we a movie theatre?” and I laughed and said: “yes!” and we headed back home.

My dad enjoyed talking to Leonel, a grandson of Abuelita’s who lives next door. He came to visit Abuelita and he, interestingly enough, is learning English. I was nervous because my dad really struggles to understand anyone speaking English with an accent (even though we all have accents, you know what I mean). I had to translate a few things Leonel said, even though they were in English, to my dad, which I think made Leonel feel bad about his thick accent. But really his English is very good and my dad enjoyed talking with Leonel. My host family started to wonder why my mom wasn’t coming down, so I had to summon her down to make sure they knew it wasn’t any bad intentions or discomfort. My dad is a social butterfly and my mom is a social shovel, she likes to go deep vs. wide. I favor the second approach.

DAY SEVEN:

We went to bed after planning the next morning, a quick visit to Paquip, a village outside of Santa Clara where I work, whenever my parents returned from church. My parents dressed up, went down to the church, and decided they could not understand what was being said nor did they want to take up the seat for people who were standing. We finished packing our bags and walked down to the Paquip bus stop. We took off and the countryside passed them by. This walk between Santa Clara and Paquip may be my very favorite place in Guatemala. The view is stunning, countryside just clutches with beautiful mountains and stunning panoramas. But the corn wasn’t growing and the earth was dry, rainy season just threatening to start. We met a few families and I even got to show them my school (from the outside).

As we passed the school and waited for the tuk-tuk, we took pictures by the coffee crops and said hello to one of my señorita students and her mom who was weaving. My dad’s natural question was “When is the church open” referring to the evangelical one next door. I wanted to run and hide when the family said: “We don’t go there, we are catholic” because I knew the question was coming: “What religion are you?” which they asked and I had to tell them. “They are evangelical.” Here it’s equivalent to telling a hymn-singing Presbyterian that you are Pentecostal. But I can’t explain that to them because it’s not my religion anyway, it’s my parents’.

After we got back from the bumpy tuk-tuk ride to Paquip, me constantly saying: “Look outside, look outside!” I don’t think it has the same experience, passing on a bumpy metal machine like a tuk-tuk as it does to walk it, greet the people in the fields everyday, dance to music by myself or listen to my favorite podcasts. We passed my host mom’s coffee fields and we quickly went to see the beans. Afterwards, we walked up to the plaza where they were preparing for the Toronjeada, a beloved tradition of Santa Clara where the men in the town throw oranges at each other in two teams. I asked: “Who wins?” and no one wins. But this represents the tradition of where it says in the Bible that the townspeople threw stones after Jesus’ died. I personally don’t remember this passage, but I haven’t looked into it.

We grabbed lunch at the same comedor as before, the yellow hole-in-the-wall. We walked back up the hill to my house for the last time and finished readying our things. We kissed and hugged my host family goodbye, and said “See you tomorrow!” to Clara and my host mom who were going to come to Pana and spend some hours with us. I was anxious about that, but I wanted to invite them. I’ve never been with my host family outside of Santa Clara except once when Clara and I went to San Juan.

My host grandmother had climbed the stairs to wish my parents farewell. It was very sweet. Not just seeing their tremendous height difference but the fact that she used what little Spanish she knew to wish my parents well. She told them not to be sad for me, that I would soon be back. She said: “We are in Santa Clara, and my name is Clara” and broke into her laugh which I adore. Leonel was over and we got a group picture, the 6 of us, and I know I will always cherish this picture.

We walked our bags through the streets down to the bus stop, found seats for each of us and waited the time for the bus to leave, listening to the ayudante publicizing the trip: “Sololá Sololá SololáÁÁÁÁ” and I could already tell that my parents would get the real microbus experience on this ride. The bus was already full when we left, which would only mean more were to come. With each stop more people stuffed themselves into the bus to occupy standing room and my parents were in the prime seats to feel all of that added pressure of over-capacity. Many Guatemalans are so much smaller than US Americans that it’s truly incredible how many can fit on these buses. One two year-old boy was throwing a tantrum “Cómprame un heladiiiiiito!!” screaming into his mother’s chest, over and over and over “Cómprame un heladiiiiiito Cómprame un heladiiiiiito Cómprame un heladiiiiiito!!” The only thing more annoying than hearing this on repeat was probably not being able to understand what he was yelling about, but actually, it was annoying no matter if you could understand it or not.

I knew I hear my dad’s thoughts on the experience later, but for now we were too many rows apart to discuss the ridiculousness of it all to someone experiencing it for the first time. When we got to Sololá after 75 minutes, we still weren’t there yet. We had to roll our bags and lug our stuff through the central park over cobblestones and through traffic but we made it to the camionetas, handed our bags to the ayudante and found spaces on the bus down to Panajachel.

When we made it to Panajachel, finally to our destination but not to our hotel, we hired a tuk-tuk to take us down to the hotel. We shoved our bags in creatively and after 10q and a bumpy ride later, we got to the hotel, checked-in, carried our bags up to our Room 202 and opened the door to our room.

Travel in Central America is not for the faint of heart or feet. We made it to our final destination to Lake Atitlán, to Panajachel.