I’m experiencing this ankle sprain on every level: the writer in me is taking copious mental notes, the foreigner is overwhelmed at how rattled they are by a sprained ankle and the human is simply hurt.

The reaction of my host family, how they surrounded and rallied around me in some unspoken emergency response routine, was an entirely unique, well, thing. I’m quietly marveling at how three people can stop their day just because of one missing adoquín/paver in the street.

I’m not sure if I’ve felt cared for like this before.

– – – – –

So… Back in Santa Clara, the three ladies of Calle Principal look after me. I’ve fallen and twisted my ankle.

Naturally it felt so strange to be really, truly injured and alone on the street. And it scared me a little to be hurt and in a foreign country. I cried. But that all quickly melted into the hour behind me as I sat on the wooden mauve chair in the kitchen with the plastic stool supporting my right ankle.

I hear them repeat “por la tentación” as they talk to each other, fretting over my current situation, and I don’t understand what this means… Temptation? They say it with a look of “What a shame.” I ask Clara what they mean by ‘la tentación’ and she tells me, it’s because of the temptation to look down at the phone, be careless and don’t care for yourself, that we get hurt. The temptation to be careless.

The tone changes; we transition from accident to recovery.

My host mom puts a pot of nixtamal on the fire (hardened grains of corn) and it’s story time. My host mom has carried her sorting baskets to the kitchen where I sit. She is sorting the grains by dropping them from basket to basket. She moves them between baskets.

They conjure stories from their pasts to pull up beside my injury and give me company (I think?). I’m learning how being hurt works in this culture.

Abuelita, all 80 pounds of her, begins to recount her own injuries in K’iche’. My host mom translates from position on the floor. I feel like I’m in some sort of mystic hospital with a Mayan Soothsayer and Cornsorter, telling their tales of woe to strengthen me in the midst of mine. Abuelita ever-decked out in her traje típico with a tela tied around her head, two principal teeth in the front, her eyes heavy from the pain I’m in.

Clara returns with the ice, and it’s my host mom’s turn to spin her tale: “Natalie, this happened to me once” they’ve made some sort of unspoken agreement to take turns.

My host sister mops the floor around me, circling me and going over the same areas over and over again. Does she want to keep busy or does she always clean this way? They ask me again: did it hurt? Does it hurt now? and I tell them I still can’t really feel it. “Oh it must be because of the pills” they say and continues cleaning corn and mopping.

To them pills from the States have magic powers. I gave her pills once for her headache and she told me later: “Those pills must be from the US because they helped me so much.” They were 2 ibuprofen. They sell ibuprofen here…

“Oh, you should have seen the size of my mom’s hand when she hit it once..” Clara’s eyes and fist widen as she demonstrates the swelling. I don’t have the words to explain how ice helps the swelling. They look at me as they try to understand. I don’t have the Spanish nuance of describing, it pulsates, throbs, pierces, roars dully, or is numb. I use my phone to look up translations but dictionaries come up short.

Again I hear “la tentación” and I don’t understand what temptation has to do with falling. Do they mean karma? Or because I’m a sinner? I’m not sure. I ask Clara why.. and they explain, it’s like the temptation to not pay attention to not take care of yourself. I’ve never heard it expressed that way..

By now, 30 minutes post-fall, I’ve listened to their stories, I’ve greeted my Tía who has come to see my foot. I’ve calmed down. I begin to message friends on WhatsApp: do they want to see a picture?

After an hour passes, I’ve watched Clara mop the kitchen floor 4 times. I exclaim: “Qué aburrido..” with a sigh and she laughs and says: “Sí pero tiene que aguantar para curarse.” I sigh: “Sí….” I decide it’s time to relocate and ask if I can lay in Clara’s bed. I hear my sister ordering my host mom to “desocupar la cama de las cosas..” and Doña Rosario hastily moves everything from the bed. I sort of let go of the crutches and fall flat onto the bed. Clara asks what she can bring me from upstairs and I request my green Spanish grammar book.

First she brings down both my pillows from upstairs. Then she brings down an armful of books, none of which are the green Spanish book, I laugh. My phone rings, it’s Johanna is checking back in. She explains I should soak my foot in a round of hot and cold water, 15 of hot and 15 of cold, to confuse the tissue around my ankle and encourage it not to swell. She is so deliberate and calm with her wording. She asks if I feel comfortable to explain that in Spanish to my host family, and I tell her “better if you talk to my host sister. I have no pride at this point.”

I call Clara and she comes immediately with ahorita voy: “Buenas tardes Seño” and she takes in Johanna’s calm instruction, me reading her face as she hears it all, returning the phone to me: “Well, you have support!” chimes Johanna. And I agree at how lucky I am to live with these women, I feel a little guilty. I ask her: “Oh, Johanna, did you receive the pictures?” And she said that the swelling looked really big (which seemed to justify my level of pain). Then she said, “Your host family looks so lovely. I saw that they were holding up your foot as you took the picture.” It’s funny, I hadn’t even noticed.

My host mom comes in and looks at the foot, which has still big as life. Clara brings me a blanket, prescient somehow knowing that I am cold. I looked back through my phone and yes, a short dark-skinned arm was supporting my ankle to ensure the quality of the photo. I’m stupid lucky. But how do I tell my parents back home? I crack open a Spanish poetry book, thinking I’ll be productive. I tell Clara what Johanna said, that my host family is so kind, and I explained that some host families are not that way. She said: “Well of course we are going to help you. No! Who wouldn’t help you? That’s not right” she explains in pure conviction, not an ounce of pride but simple, earnest feeling. Of course I can’t translate the person of Clara into English, but in Spanish I can her recreate her conviction perfectly. It expresses her spirit that I can’t transfer to English. Spirits are not lingual.

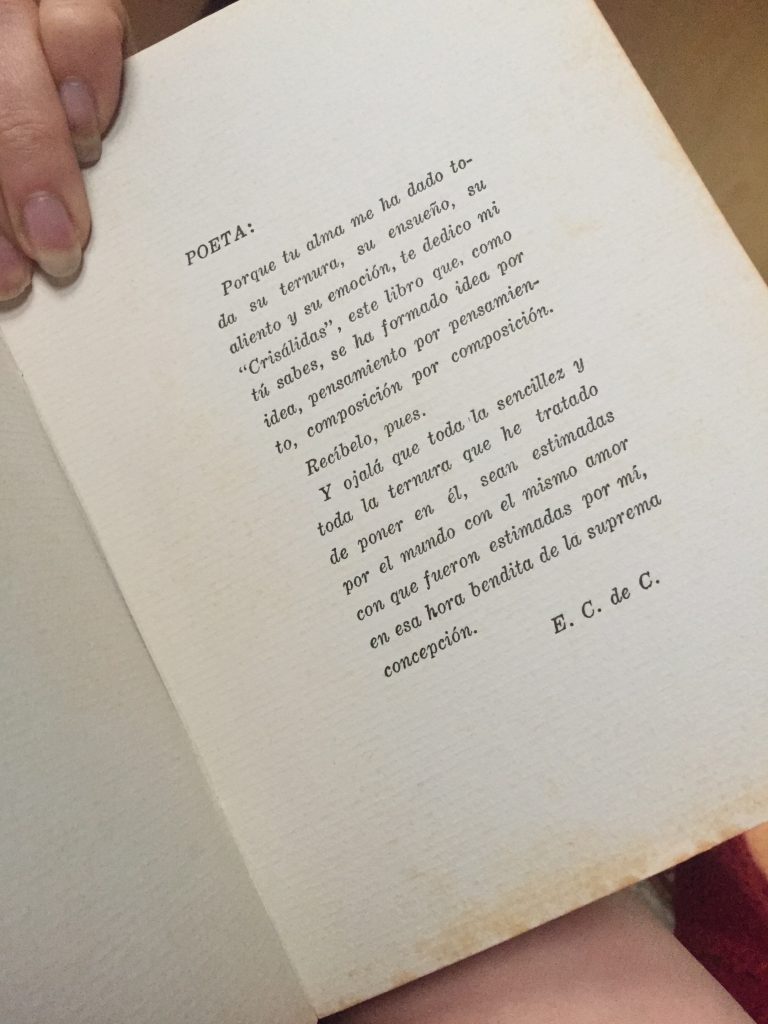

I can sense their preoccupation but don’t know how to assure them that this was a stupid, dramatic accident. I read a poem from all the unwanted books Clara brought me including my own journal. The pages are beautiful, the paper an expensive, beautiful light blue with quality thick card stock. Once again I try to understand the prologue, this time I remember a few words from looking them up last time I tried to read this book, words you don’t know unless you’re reading poetry.. not unlike words you don’t use until you’ve injured yourself.

The actual injury was one thing, but the aftermath: my host family’s reaction, their care for me, their stories and their concern all manifested according to who they are. And it was really a beautiful thing to see in spite all the pain in my foot. Being helpless is a good thing to practice if you want to learn how people help.

And I’m useless without one foot. And it happened in an instant.

Reposo means recovery, it means healing. It makes me think of repose which seems peaceful. Another word I learned in Spanish.

And now I’m a gimp.