Before I begin, I am not a journalist. I think of this post as a journal entry, unwinding experience vis a vis my emotional reaction. There is a textural context I have yet to unwind and explain through these posts, so please take into account that this is one situation about one neighbor on one day not about the Guatemalan context at large. Thank you! Please comment as you feel inclined and we can have a discussion or I can answer more questions from my perspective.

* * * * * * * * * *

She is 13. She lives next door. Her mom’s name is my name. I don’t know her mom’s age. I’ve been meaning to seek Leslie out ever since I sat on the edge of the concrete curb and interviewed her for my site integration assignment. I was instructed to interview a girl and boy joven with a list of questions. When I saw her brother inscribir/sign-up for classes in the director’s office, I made a mental note to check if his sister would also attend. Since then, I hadn’t seen her at school yet.

So I made a mental note to chase her down. After all, she lives NEXT DOOR. What’s taken me so long in the first place? It’s nearly March and school started in January. When I saw her on the curb, facing in to her house with her back to the traffic, I was tempted to keep walking I’ll come back later but I knew this was my opportunity. “Porque no estás estudiando?” came out the words as I stood over her in my work pants, my work bag in hand.

She looked at me, smiled a beautiful smile, and offered more or less a shrug. She didn’t break eye contact or the smile.

From the interview in December, I know this beautiful young lady is smart, loyal and kind. She couldn’t define self-esteem but she answered the rest of the questions with calm and honesty. At first blush, I’d say she is more loyal to her mom and the needs at home than she is to herself. But I’ve learned something about Guatemalan culture through some of these interviews: being loyal to your family is being loyal to yourself. This I can say por fuerza.

I asked Leslie: “Trabajando?”

And she said nodded “Sí”

And I said “En la casa?”

“Sí”

And I said “Con tu mama?”

“Sí”

And I decide that I am going to seek this out and state my case. And I ask where her Mom is?

She says “Allí adentro” and gestures inside to a woman seated on the opposite end of the house, looking over a table in silhouette. I ask if I can come in and Leslie says yes and as I walk in I say “Con permiso” even though Doña Natalia has headphones in. I say “Hola Doña Natalia” I wonder if we might be the same age? She has a 13 year-old, she might be older than me or the same age. I think the 13 year-old has since disappeared. I look at her mom and say “Leslie no está en la escuela, y lo noté porque su hermano ya está estudiando.” (I noticed Leslie isn’t going to school and her brother is). Doña responds “Sí. Él está en tercero basico.” (Yes he’s in 8th grade).

I stand over Doña as she makes a thin beaded rope of coral, light blue and gold. I love these colors. I ask what the strip is for, and I ask “for a necklace?” and she says “Sí.” And then I try to wrap it around my neck. I ask but how does it fall? and She says “I don’t know what it’s for” with a smile. I hold it up to the light, it’s delicately woven. These beads are tiny and I hardly know anyone who would have the patience to make it minus Sarah in Ketchikan. I say: “Pues porque Leslie no está en la escuela?” And she says “No sé. She doesn’t want to study” with only honesty, no tone of defense. As if that was a sufficient enough answer: she’s 13 and doesn’t want to study, so she’s not. I’m not sure if I am treading but I continue: “Es muy importante por su futuro!” And she says “Sí” also honestly, with recognition, with calm. She continues with the beads.

I say “Where is that Leslie?” Trying to keep a playful tone. I call her name out but she has disappeared to a room. I approach the small window and say “Leslie, está escondida?!” And the kids who surround me (side note: children are always afoot in these interactions, they linger, they stare, they provide oft-helpful color commentary and most of all blatant honesty). At this point the three neighbor kids/primos are watching the interaction and seek out Leslie for me. They find her (Best Sidekicks, I tell you) and say “Aquí está Leslie!” And I enter the room, she was ducked down under the window and shoots up with a paper in hand, pretending she’s been looking at it all along and not hiding.

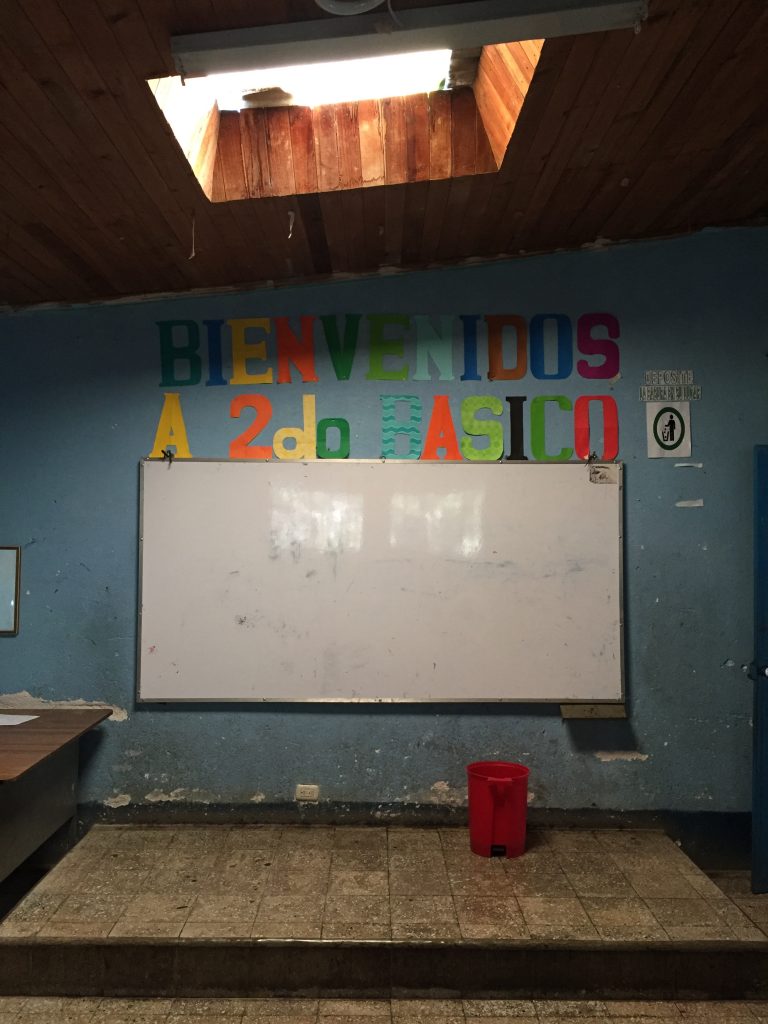

My eyes level with hers in this dark kitchen-plus-bedroom and I ask “Why don’t you want to go to school?” She doesn’t respond, quietly half-smiles half-waits. I say “No quieres ir?” as her mother told me. And she doesn’t respond. And I say “Leslie, usted necessita inscribir en el próximo año!” And I wait. She doesn’t break eye contact but she says nothing with her mouth. But her eyes are saying something. To be honest, I don’t know the language they speak. But they are pure and patient and lovely and I want them to see more than the dusty walls of her home as she sweeps and the edges of the pila as she helps her mother prepare the food for each meal to keep the men and siblings happy and fed. I look around the room- “is this your room?” And she says “No- cocina!” Oh good, she does talk. I respond “But whose bed is this? And she says the name of her brother, the one in school. Sensing a trend? And I say once again: You need to study Leslie “Para su futuro! Porque si su hermano ya está en la escuela, used puede ir tambien. Por su futuro.”

I start to walk to the edge of the bed telling myself: “I think I’ve made my point”. I look at her. And the three kids like church mice surround all 5’7” of me, looking up like I’m some Statue of Liberty, and I say “Yo voy a asegurar.” And I say “Ok? Los dos juntas” And I wrap my fingers around each other and hold them up to show her because it’s a promise. “Yo voy a asegurar.” And I approach her seated on the bed, kiss her cheek and offer “Se cuida” as I exit. She cursorily responds “Gracias” as if it’s a normal interaction on the street: Love you k bye.

I approach her mother again with the beads who has been joined by another mom because where there is one woman in the house there is often another, an aunt or cousin or sister or neighbor, and I say “Ella necesita ir a la escuela en el año que viene. Por su futuro.” I feel like Bill O’Reilly, if I just say the same thing emphatically over and over, maybe it will stick.

This is the story of Peace Corps I thought I would read, write, live. Stories of rescuing the less-fortunate from unfortunate situations and walking away with a feather in my cap. In truth, this is not the story of Peace Corps but it’s probably the one you’ve heard. At moments I feel like a stereotype here, like a Sarah McLaughlin song is playing in the background as a tall bearded man asks for your money to save the animals. But my work here is not about saving anyone: this is about a partnership, about strengthening bonds with other cultures and developing understanding and hopefully applying new skills where possible. I will never claim the infomercial life, but at moments, I still feel like I’m in one.

In that last glance before I left her room I saw in the eyes of this child many unspokens and perhaps I’ve projected a story onto her irises, one that she isn’t telling. Who doesn’t want you to go to school? You or your mom or a little bit of both? Maybe you don’t want to go or you don’t think you’re capable. Or are you being disloyal to your mother, leaving her to do to the work of the home alone? Beading? For me a deeper question is: Didn’t her brother ever leave for school and wander: “why isn’t my sister coming?” or wait for the other students to ask “Hey where’s your sister?” or did that even happen? Other girls are in his class, I’ve seen it. It’s not a school of only boys. So what gives?

But I made a promise and maybe it was propelled by the recent enlightenment of my tremendous privilege and I am trying to make up for the years I was in a cocoon of self-concern, or maybe it was just because this was an opportunity that was too relevant and accessible not to take. I need to get one girl in school. One thirteen year-old. Because she’s not going. That’s it.

Chasing down neighbors and telling them to go to school is not in the project description. The work of the project is to build youth leaders, to encourage sexual health and anti-drug addiction and toma de decisiones and comunicación positiva. But as any volunteer has asked themselves (a title with which I only loosely identify: volunteer): where does the line between volunteer and good person get drawn if at all?

And I’m not sure if I was a good volunteer in those moments. Anyone who has taken International Development 101 will tell you that chasing people down and saying “CHANGE!” doesn’t work. You have to build relationship and recognize what’s good about a community before you try to support it. “Change” is not the goal so much as support, resources, fortalezando. Ostensibly America’s Next Top Model contestants go on the show to learn how to be better models, not to win. Only one person can win. I think that’s a terrible example and I already regret using it but let’s continue and let me say before I finish this post:

This is one person in Guatemala. This is one young lady. I hesitate to tell this story because it’s very easy to peg the stories of Guatemala, of Central America, onto the story of this one young lady. Easy would it be for an Estadounidenses to say: “So that’s how it is down there?” Down there. Eager to have picture to stick on my whole 2 years in the name of understanding. (I swear to Jehoshaphat please don’t refer to Guatemala as “down there” when we meet up for coffee). While this is a day out of Leslie’s life, there are many stories of neglect and deprivation of the youth in my own country, privilege or no privilege. And I could write about machismo or lack of equidad de género here in country or the affects of guerrilla on the Indigenous People or Hofstedt’s spectrum of collectivism vs. individualism but at the end of the day this was just one lady chasing down one kid and looking at them and saying the words “Your Future.”

I want to be more like this kid in a lot of ways: Her Mona Lisa eyes. Her commitment to her family. Her smile. Her potential.

I guess the point here is that I had A LOT OF FEELS after this very brief interaction. They go in lots of directions and I am still feeling them. But I am going to ask again next time I see her about school and every time I see her I am going to ask. And maybe what I need to do is spend time with her or invite her to help me on a leadership project. Or perhaps I need to be still for a moment and recognize that I can’t control the future at all.

But I want to believe *key word: want to* believe that there’s a reason I asked to interview her specifically, that she is my neighbor, and that I am working in her school. And I want to believe in her future.

Thank you for reading and for understanding all of the thoughts and the feels.