I didn’t even see it coming.

I never know how I am going to feel as I turn left into the parking lot of the Benedictine Monastery with not a cloud in the sky. With any type of social work or service, you can’t predict how you are going to feel because the work is person-centered. And as I stepped out of my car into the heat of this desert day in June, so did the people arriving from border patrol.

I noticed the driver, uniformed, overweight, belly spilling over her belt buckle, sunglasses, and it made me feel sick. Before you call me out for body-shaming (which I would do if I were you), I don’t care how this woman is shaped as it relates to her worth and identity. I will explain later why I made this observation.

The long, grayish bus said “BORDER PATROL” in dark blue letters. I’d never seen this part of the process, the arrival of our guests. I walked alongside the steady stream of people exiting the bus, not sure what to say: “Hola, Buenos Días, Bienvenidos, Pasen adelante.” And I felt a rush of gratitude for this added layer of perspective. Walking this process with guests who are going to a totally unfamiliar place (not the first and not the last) helped me see it even more completely.

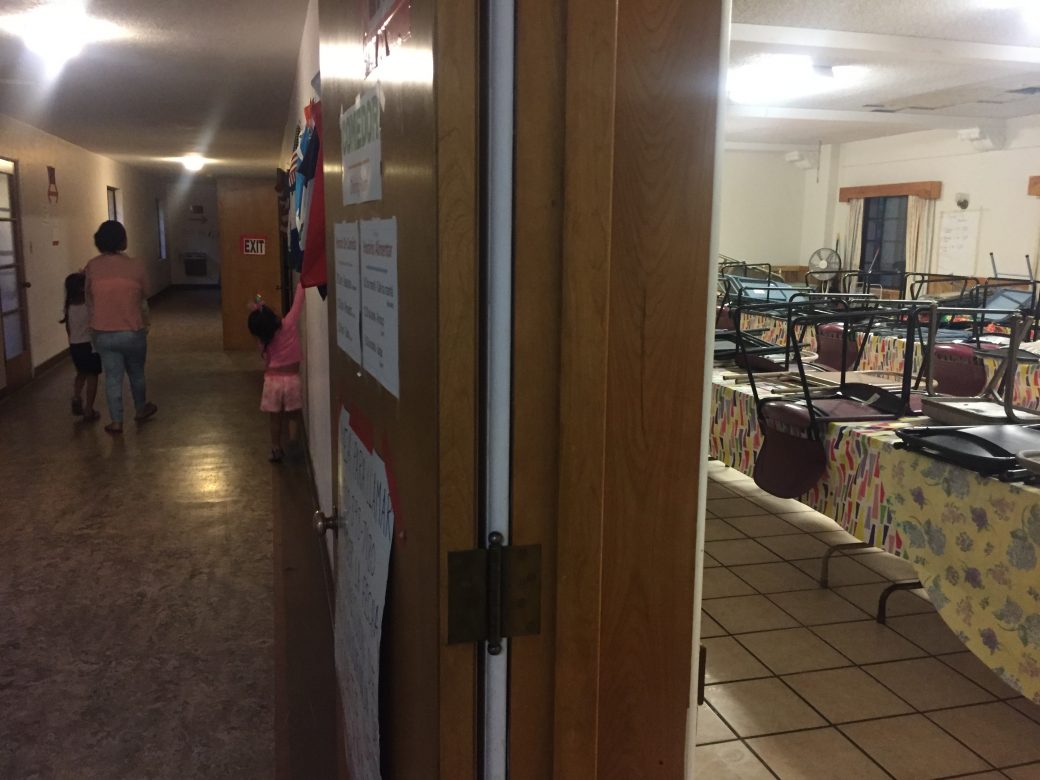

We passed the portable showers, port-a-potties (plumbing has been down in the monastery for over a month) we pass directive signs on multicolored, repurposed cardboard: “Dry Good Donations Here, Perishable Items inside, Clothes Donations Here,” we walk an incline to the patio where some children with parents are playing on heat-warped plastic toys next to a yellow sign: “No se juega aquí” (the doorway) and I swing open the exterior porch-like door and everyone follows.

I stop at the sign-in book for volunteers, look for my nametag, hang it around my neck and continue with the group to the sanctuary. We pass the Central American flags posted on the walls and my heart leaps when a Father whispers to his son: “The Guatemalan flag!”. Maybe they felt a little at ease to recognize an emblem of home. Hell, I feel a little at ease to see that flag and it doesn’t mean near as much to me as it does to them. I’m so grateful for whoever hung those up.

The sanctuary, like most, has two sections of pews. In the group of pews on the left side sit a group already being processed. They arrived from Border Patrol earlier today. The arriving group of guests sit in the right side of the pews. I notice things I hadn’t before: namely, shoelaces. Everyone is receiving shoelaces out of a box being passed around. I look at their shoes and sure enough, no laces. What a strange thing; I ponder it. And I walk over to someone who I recognize from my intake training: “Why do they get their shoelaces taken away?” she says: “I don’t know but they gave shoelaces to the last group, too.” I file this away in my mind for further investigation. My immediate thought is: “So they can’t run.”

Next eager volunteers are ready with trays of paper cups with water and watermelon to give to the group. I remember Kat’s words at my training: “We don’t know the last time they ate, and many will gorge themselves because they don’t know when they will eat again. So we give them fruit and water in place of something heavy. Otherwise we end up with guests in the infirmary because their stomachs have shrunk from not eating for many days and heavy foods make them sick.”

Delle walks up to the group. Delle is our “Intake Lead.” Leads, I have learned, are responsible for herding the volunteers (eager and ignorant as many of us are) through the intake process. She greets the guests, gives them the exposition on who we are and considerations during their stay. She also assigns guests to their rooms for the night and is there to answer our questions as new intake volunteers are constantly coming in (such as myself in June). She is the captain.

I sense within myself low expectations for Delle. Why? Ageism, simply put. I see that she has short gray hair and appears to be an older white lady and I brace myself for some terrible Spanish. I am surprised. Delle speaks with the confidence of a seasoned second-language speaker and, lest I forget, the grace of God.

I am going to write in English here, but all of her words were in Spanish: “Welcome to the Monastery. You have come a long way to get here. We are not part of the government, we are a volunteer-run shelter and we do not make an income for working here. The shelter provides a place for you to stay as you are waiting for your travel arrangements to your destinations.”

“Now, before I explain how the shelter works, I want you all to take a deep breath with me. Exhale all of the violence you experienced crossing the border, the hardship of leaving your home and your families, and inhale peace, freedom and the love of God. Decimos juntos: “Soy libre.“ And they said: “Soy libre!” And she told them to repeat it again in strong voices: “Soy libre!”

Soy Libre.

I saw tired faces, tears and emotion. Some were too tired to pay her much credence but most were attentive in spite of their exhaustion.

At this point I see volunteers cutting tight bracelets off of the guests’ arms with scissors. They each have two on: blue and yellow bracelets. They’re the thin plastic ones you wear at an amusement park that you cut off at the end of the day. You can make the obvious connection with the metaphor here, it’s like they are being set free.

I am not religious but as Delle tells the guests that she is a pastor, and that she is going to pray with them, and as the groups bow their heads and cry out to God while she speaks words of peace, hope and love over them, I would believe anything she told me. If she told me the world was ending tomorrow, I would burn all of my things tonight and sit by the pool waiting for the earth to start shaking. I don’t care what we believe about how the universe came to be or who created it, but me and Delle, we believe the same about love.

After the prayer, while shoelaces, folders and snacks were still being passed out, Delle went into the logistics:

“We have a cafeteria that serves…. We have a travel office that will help you to… We have bathrooms and showers outside… A normal stay here is for 2 nights. Please stay with your children at all times… Please help to clean up the facilities after your stay… Do we have any Portuguese speakers? How about Mayan languages? Okay, which language? K’iche’, okay.” (You can imagine my ears are perked) And Delle closes with “Welcome.”

She turned to us volunteers and said in English: “Okay Medical can start doing their questionnaire, raise your hand if you need translators.” And I zoomed over to a kind-looking blonde who raised her hand. She told me she is a nursing student. “Where do you want to start?” she said. And I pointed to the side that raised their hands as K’iche’ speakers. You can’t blame me, even if I don’t know enough to translate K’iche’ I wanted to know them. Together the nursing student and I went through three interviews, passing from pew to pew and asking the parents questions about their physical conditions. Immediate injuries are the most important thing for the shelter to address, which is why the medical intake happens before the system intake (which is where I come in). As we ask them about their physical conditions, they mention little things here and there: “I am not urinating consistently but I think that is from all the travel.” (Read: I can’t urinate if I am dehydrated). Others complained of itchy feet, and a few little girls had lice in their hair which some of the medical intakers investigated with plastic gloves. Other than that, everyone appeared okay.

Once we finished these medical interviews, there were only a few folks left waiting for their intake processing. I debated whether or not I should just go home, but called a name on the list instead. I could use my phone to do the intake without my computer. I pulled up the link as we sat at the table. These two guests were from Honduras, a father and son. His son was so excited and happily playing games on his dad’s phone. We quickly went through the questions and I advised them about the amenities. They seemed to recognize other people they had met at the border while they were waiting on the Mexico side. That would be a really specific way to start a friendship “Hey remember when we were mistreated at the border together?” I was saddened by their answers: “no they didn’t give us food while we waited, just juice and cookies.” How many days were you there? “Three.”

This is why the driver’s weight made me upset. She represented something. We have an obesity problem in the country (which I know is not a simple situation in its own right) but here these people are starving at the border while many of us are overeating within the borders. I don’t know, it’s not her fault. It just represented something more to me.

I flip through their papers to find their sponsor’s name with their address, phone number, and the corresponding court date that’s been assigned them at the border. I am meant to look for any inconsistencies or errors in the paperwork (sometimes their sponsors live in California but assign them to a court hearing in Virginia, for example); typos, confused dates, locations and times all must be righted as soon as possible. The border officer whose name appears on this paperwork always has a white-sounding name like Trevor or Lisa. It screams of white supremacy and perfectly illustrates the hegemonic relationship between races. Of course all of these thoughts amble through my head like lost hyenas while I interview them in Spanish and learn as I go.

Once I completed their interview, put their room tag into the plastic sleeve of the entrance to the basement: “List # of people in party, the date they arrived and their room number.” I forgot how to say “basement” in Spanish. It’s been a long time since I learned that word (10th grade) in a Paso a Paso illustrated in my Spanish text book. There aren’t basements in Guatemala (to my knowledge) or at least, I never once needed that word while I lived in Santa Clara. We picked up their bedding/towel pack and the important paper on legal advise once they arrive to their designated State. Now they are free to eat dinner and play outside if the boy wants to. It’s tremendously hot but there is something to feeling free for the first time in a long time that might want to make you stand outside in the heat anyway. Even though they are not approved residents. Far from it. They have to show up for their court dates, and that process I don’t pretend to know anything about.

I’m just an intake processor at a shelter a part of greater, rusty system meant to keep people out and away.

Basement in Spanish is “el sótano.” In case you wanted a reminder like me.