Maestra de Inglés, English teacher. I’ve always wondered if the word Maestra and Master are related. Either way, I’ve never had such a title.

When I gave a diplomado in early 2018, I wanted to attract interest from folks who wanted to learn English so I could reach some of my project objectives to service providers. That’s a bunch of gobbledegook to say that I wanted to open doors. As a YID volunteer (Youth in Development) my job is two-fold: teach youth and train service providers. But the second part has been…. well, it hasn’t.

I had a measly turnout to the diplomado, and only a few teachers came. I learned a hard lesson. If your community doesn’t ask you for it, they won’t come for it. If you build it, they won’t necessarily come. Sure the community asks me to teach English constantly, heck half of them still think that is what I do, but no one asked me for a diplomado.

One Thursday morning only one person showed up, so we did not have class. Her name is Juana. To be honest, I don’t remember our first interaction. Oh wait! I do. I was going down to the restaurant Los Olivos, the fanciest restaurant in town. The only restaurant in town. And she worked at a store selling appliances and one day it was raining, and I took shelter outside of her store under the awning. She is very curious, she asked me all of the same questions that everyone else asks. She told me she wants to learn English, that her beau lives in Sacramento. Who immigrates to Sacramento? No shade, but who?

She asked for my Facebook name, me thinking, I don’t really want to be Facebook friends. In Guatemala, Facebook friends is different…. You get lots of messages late at night, lots of gifs or religious memes and figuring out who the person actually is can be difficult because their names are like code names. Me? My name on Facebook is my actual name. You haven’t seen the things I have seen. I think it’s because people look at Facebook purely as entertainment in Santa Clara, so they make up weird code names that I can hardly remember or understand. I would share examples but just take my word.

But when she was the only one who showed up to my diplomado, I started to feel differently about Ms. Juana with the Sacramento boyfriend. She was the only punctual one, more punctual than me, and she always helped me carry the projector, clunky computer with charger and my materials bag, all the way back down to the muni. On the day that only she came to class, she sat diligently at the wooden desk and continued to make bracelets out of small beads. The patience, I thought.. Then she gifted me one of the bracelets, she took my picture and posted it immediately to Facebook: “aquí agradeciendo a Dios para otro día de vida…” another Facebook norm. Posting pictures of yourself with a religious message, but doing normal things like posing or walking or eating.

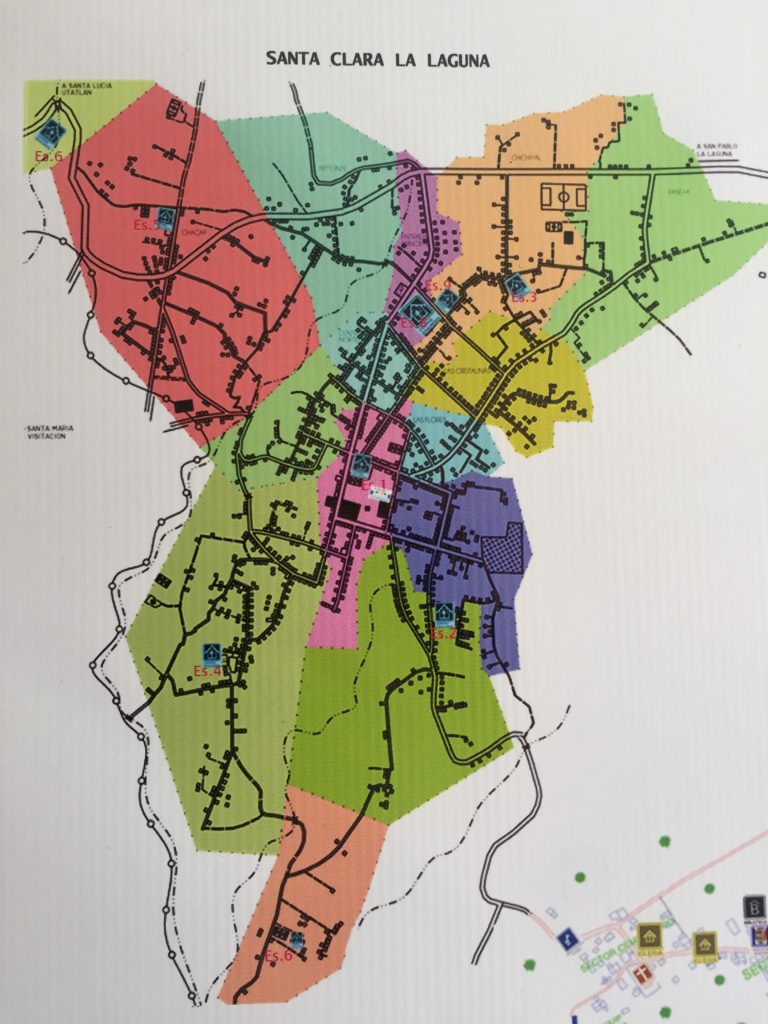

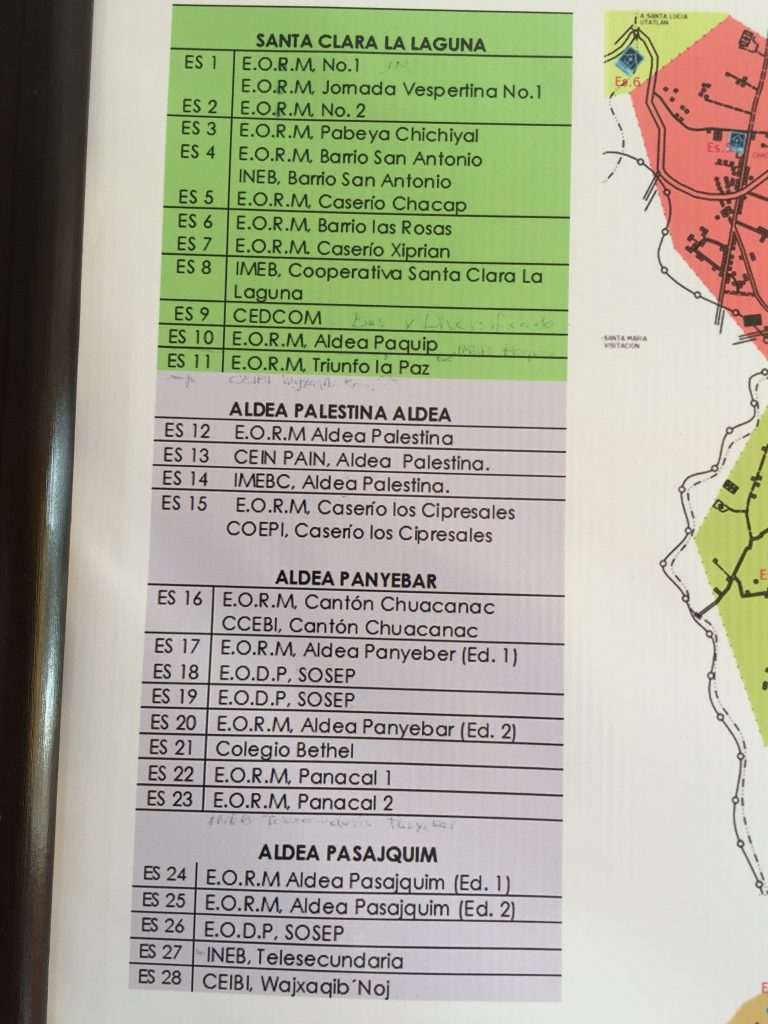

Juana invited me to Pasajquim, it is an aldea of San Juan that’s far. Aldea means an outlying village of a bigger community. Aldea is one of those words volunteers forget to say in English, because there’s not really an exact translation that conveys what it is. Village will do. I’ve lived in Santa Clara for over a year and a half, but I’ve never been to the outlying aldeas. So on a Friday, class was cancelled, so I took advantage of the time and told her that I would come for lunch. I was supposed to visit her on Thursday afternoon but I ended up playing with little kids in Paquip too long. I texted her that afternoon: “I’m so sorry, I’m not gonna make it. They say there won’t be a bus for me to get back to Santa Clara if I come to your house now.” “Stay the night! No problem!” she responds. A woman who I hardly know inviting me to the stay the night, I’ve never even been to her house before. I’ve never even stepped foot in her town before! I stand firm: it will have to be tomorrow. I feel a little bad ‘cuz I thought I could kill two birds with one stone, visit my kid friends in Paquip and make it to Paqajquim and home in one afternoon. No way. Time here is not portioned, it is lived.

I realized on Friday morning that I also had some errands to do in these aldeas, needed to get signatures from each school director in the aldeas for an event. Signatures and sellos (official stamps) in this culture, for everything. So I made phone calls to new numbers and crossed my fingers their numbers hadn’t changed. Everyone picked up, casi un milagro. After several phone calls: “Hola Director Mynor, se habla Natalie de Cuerpo de Paz… Fíjese que…” “Hola Seño Mariana… se habla Natalie de Cuerpo de Paz…” “Yo tengo que llevar una solicitud de permiso por parte de la supervisión con usted hoy en la tarde. Es que, queremos realizar una charla sobre el hábito del cutting,” …. I get to the buses at 12:15, thinking it will leave in 15 minutes…. I thought wrong, “it will leave in 50” they say. I’m surprised. Most of the buses in Santa Clara leave every 15 minutes, but this was my first clue: you’re going somewhere far, far away.

I buy some internet time close by, sending in the finishing touches on a grant completion report. I grab my things and head back to the bus 10 minutes before 1. Juana has been preparing lunch for us and I am late, but I didn’t know about the infrequency of the buses… I am updating her via text: “saliendo ahora, perdón amiga..”

The bus leaves. This is a normal microbus, but I don’t know the driver or the destination. We drive the paved road to the intersection and, instead of taking a left like I have done every time I come to this fork, we go right. Two roads diverged in a green campo, I took the one without pavement. We begin to bump along. To be fair, I have taken this road once before but I did not go all the way to Pasajquim. And it wasn’t on a workday, it was on a Saturday for a wedding. We pass Palestina, we pass Panyebar and we. keep. going. The unfamiliar surroundings settle in around me as we pass the world by. The world looks practically untouched. There is green everywhere. The fog sets in like a thin cotton in the air. Bump, bump, wiggle, wiggle, bounce, bounce, on this obstreperous route.

I am starting to think: “No wonder the bus only leaves every hour.” I look around at the bright lights, big city. Jokes I just get caught up in a Taylor Swift song. My mind doesn’t peregrinate because my body is doing the wandering. I calmly sit and bounce up and down and around. I’m not uncomfortable with the mystery of this new place, just completely unfamiliar. When we finally pull up, 40 minutes after we left Santa Clara, I see my friend waiting at the bus stop. Seño Juana, standing up straight and looking at me. Her mouth open, not smiling or frowning, her gold fixtures gleaning from her front teeth. She is wearing her corte, the indigenous skirt, but with a simple blouse meant for housework: not a güipil. Cooking in rural Guatemala is almost a sport, rolling the maize on a stone to smooth the dough, clapping together doughy circle after doughy circle, adding more wood to the fire, and flipping the tortillas careful not to burn your fingers. You sweat when you cook.

“Hola Amiga” I say dispensing an air-kiss to her cheek after I’ve hopped off the bus, bending down as I am a giant at 5’7″ to her maybe 5’3.” “Hola” she greets me “ya llegaste.” We begin to walk. I watch my path for animal poop or an uneven paver that would send me facedown and pancake flat. I take in the aldea as it takes me in. It’s not all that different from Santa Clara, but it is not the same. I think: This would be a different experience, if Peace Corps had sent me to live in an outlying village instead of the center pueblo.

This is what I imagined my life to look like when I first thought of Peace Corps, a foreigner walking around a tiny village, greeting people hello. Belle with a song but no book. You can’t walk and read in villages, that’s a Disney adorno. Little kids appeared, grubby-fingered, small and curious, run to doorways and stand at attention to take in everything that I appear to be.

Do I emit an odor? Because without making a noise, they always appear. The gawkers. I bathe regularly, I don’t use demasiada perfume. Every inch of me is being observed, like a runway model without the runway or the model. I am tall, I am white, I am a woman with very short hair (obviously uncommon), I have an accent, but surprise: I speak K’iche’. Such a combination incites laughter, intrigue. I am the most interesting thing that will happen in Pasajquim today, maybe this week, maybe this month. I am used to the attention in Santa Clara, but against this unfamiliar backdrop it feels more imbalanced: the distance between us.

Pasajquim is green, the houses dotted between the trees and the earth painted around us like I’m in the center of a Bob Ross painting. I don’t know why I say Bob Ross except I think of repetition: trees, green, a small home here and there, worked land, people walking by with baskets on their heads (did Bob Ross draw developing countries?), greeting neighbors. No pavement, anywhere. Pavers. It’s hotter than Santa Clara. I wonder how high up we are. Are there mosquitoes, malaria? Is this where the bananas grow?

As we walk, we chat about the journey, how long she was waiting… I say I am sorry, I didn’t know about the infrequent bus schedule. I remember how punctual she is and how frustrating that must be in a subculture where clocks are out of battery and serve as decorations. She tells me about how she waited for me yesterday but I never came… I say I am sorry, but it just didn’t work out. We turn a corner, and we walk down a winding road. What type of house does she live in? This mystery will soon be dispelled. Why does seeing someone’s home fill in so many gaps as to their life and character? Especially in a place where you don’t know if the house will be made out of adobe or brick, will they have a toilet or a latrine? Will their light sockets have lightbulbs? Will they have light sockets?

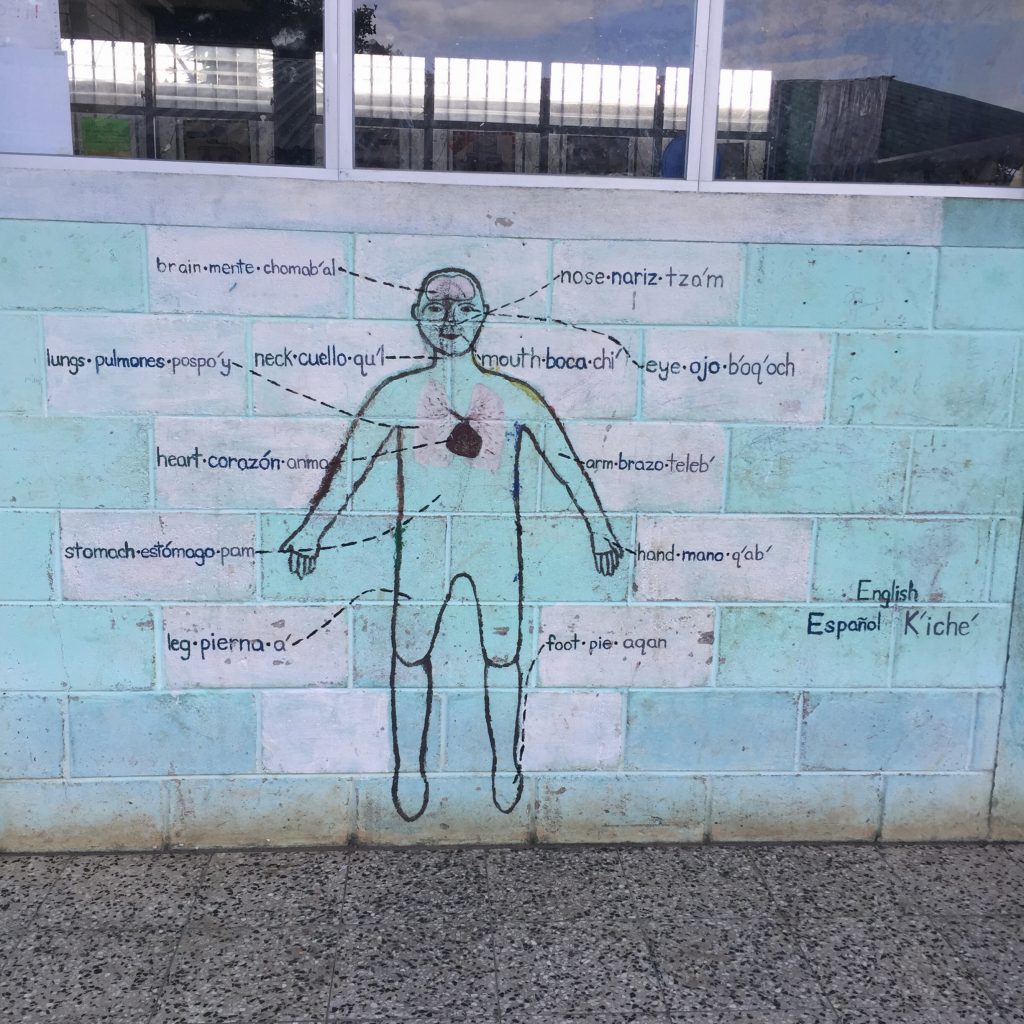

We stop at what I assume is a relative’s house and she says “Ella es mi maestra de inglés.” She doesn’t introduce me as Natalie, she introduces me as My English Teacher. Funny because I am not an English teacher. I included English as a part of my Youth in Development training series to attract attendance but it’s never been my job or my job title. But English is a status symbol, and what’s more, it is my native language. I am a person of a certain status. I am from the United States, I speak English, I have a passport, I have privilege. I am a guest in Pasajquim.

She opens the door to her home, I don’t think it was locked, and we have two small boys in tow. Her nephews. Her home looks very clean and nice. She hands me the remote to her flat screen tv, immediately, and says: Turn on what you like. She heads to the kitchen. I trouble her to show me her bathroom and find myself relieved to not be traumatized. The next mystery: what will we eat? “Can I help with anything?” and she replies: “¿Sabes como tortillar?”, do you know how to make tortillas?” and that renders my offer empty. No, I don’t. Her nephews are streaming something on her cell phone, sitting close to the window where they get more reception. Even in a more remote pueblo, tv on telephones ends up in the hands of little people. What is this new world we are swiping ourselves into?

The home is clean, cement floors. There are no doors between rooms, but curtains. I switch the tv to a skateboarding show and flip through her photo album that she handed me between trips from the kitchen. She wants me to feel comfortable and entertained. I talk to the boys, play around with the boys as necessary, talk to the Meesh (cat) who appears outside and keep repeating how beautiful her home is. I snap Meesh’s picture and show her. I stand and gaze up at all the pictures on her walls.

Juana used to work for a bank, no wonder she is punctual. “How did she land this job?” I wonder. It’s not everyone who can secure work like that. She comes in and out of the kitchen while she finishes making preparations. She unfolds güipiles she is sewing. That is a common form of work for women who work in the home, young girls too, they follow drawn patterns with their brightly colored threads. They sell the güipiles to vendors, to whom I don’t know, but to somebody. I wonder how much they make on each one. Sewing is practically a lost art form in the USA, especially in the swiping generation.

I feel totally out-of-place but totally normal too. I’ve grown accustomed to being unaccustomed. It’s a delight to be in her home, but still it feels like work to be hosted, to be “on.”

We sit, we eat. She feeds her two nephews like they are her own children. Juana is not married. I am relieved that there are noodles in the caldo. I am tired of vegetable soup, with a few pieces of vegetable, a small piece of meat, and tortillas to supplement the carbohydrates you didn’t find elsewhere. But this soup has noodles, and flavor, and what’s more, I brought avocados.

When we finish lunch, buen provecho, muchas gracias we echo to one another, we leave Juana’s house and I tell her I have to leave soon. It’s almost 3 o’clock and I need four different signatures from four different school directors in four different places I’ve never been. Where are the schools? GPS no hay. But I have no pena asking people for directions like I do in the States. No one in the States asks for directions anymore. “What are you, on Plymouth Rock?” I feel like they would think. But we aren’t in the States, honey, for one because I had to meet and visit with all of Juana’s relatives before I could leave. My iPhone 6, on it’s last legs, still has the best camera around, and so I take pictures of the whole family. They pose, various times in various groups, they laugh at/with my K’iche’, and eventually Juana walks me to the school. My favorite kid is wearing a tank top, hat and Sponge Bob bathing suit, his imitation crocs on the wrong feet. I call him “My Chomito” because Chom is gordo in K’iche’. My Fattie, surely that would fly like acid rain in the US. Juana’s mother is beautiful. As many women in their 70s do to me, she giggles internally at a gringa speaking K’iche’ and smiles calmly. A woman who has worked her whole life for the generations around her. Her hair is curly. We take a photo together. To me, she is the most beautiful woman. Seño Juana has changed into a güipil for the photos and school visit.

She recognizes the school director, and we shake his hand. He escorts us to an empty classroom of elementary school chairs and asks us to wait. The middle school students only study in the afternoons and elementary in the morning, but they often share the same building. The director is dressed in dark pants with a belt, not an unattractive fella, but I quickly dismiss any ideas because he is surely married. Campo culture says you are married by 22, if you’re progressive. I get his signature, chat un rato and Seño Juana escorts me to the bus. It’s not leaving for another 30 minutes. I am pressed for time. I need these signatures because I am not going to come back to these pueblos until the event. Juana waits with me on the bus until it’s time to go. I learn something new, the way this bus leaves town is by riding around and honking the horn profusely, calling all customers, making the trip worth their money in gas. After we have circled the whole of Pasajquim (it takes about 10 minutes) advertising our departure, we drop Juana back to our starting point at the center of town and leave Pasajquim. I am checking the time, hoping I can make this work.

When we get to Panyebar in 20 minutes, the next closest aldea, there is a cute center of town where all of the buses pass. I already feel closer to familiarity. I ask two store vendors: Where is the first middle school? And they point: “arriba.” I climb upward until I meet a large metal gate and enter the school, asking for Seño Mariana. And guess what, I have to pee again. The bathroom lottery. I am relieved to find that the bathroom doesn’t have it’s normal urine aroma and there are plenty buckets of water to flush. When water stops running after the mornings, the way to flush the toilet is simply to pour water into it. This school must be organized because there are over 50 small containers of clear water ready to be used. In my other schools, I’ve never seen such. You just pee on top of someone else’s pee and wait for the next morning when there will be water again. I miss the days when I was a camel. I’m 32 and I drink about 1.5 liters of water a day, so I choose my own adventure every time I leave the house. Even as water is supplied, toilet paper is each man for himself. Or should I say each woman for herself, we use more toilet paper.

I am reminded that I know the Directora Mariana. She and her sister invited me to lunch one Saturday in April where she showed me all of her pictures of her trip to Japan. I remember this distinctly because it’s very rare to meet someone in Santa Clara who has traveled outside of Guatemala, much less Japan. The school was perched on the side of the mountain, and I stopped to take a picture. The view is breathtaking, even when cloudy.

I get Mariana’s signature, confirm the time of the charla, and head down the steep hill asking “Where is Bethel?” the second school I need to find in this aldea. Strangers direct me to a cemetery and I turn left, asking someone else, and walk up a steep incline towards the school. I walk into one official building which is not the school, turn around and eventually find the right place: school.

I ask for the principal, we sit and chit-chat as I have never met him either. He signs my form, we make plans for the day of the charlas and I scurry out of the school, down another steep hill to a tuk-tuk that takes me to the next and final aldea, Palestina. I replay in my mind the part where the principal just told me all his students said I was beautiful and that he should date me. I think this was flirting, but surely he is married with children. One doesn’t negate the other here. The tuk-tuk I board is eventually stuffed with nine people, three hanging off the edges, three in the back row, the driver, and two up front. All nine of us on three wheels. I maneuver my way out of the tuk-tuk with all of my things and completely forget to pay, it doesn’t occur to me until I am laying in bed that night. And the driver either didn’t notice or didn’t care, odd.

I huff it up to the last school for the last signature, find the director as there appears to be some event going on, and the secretary signs the document for me.

I am amazed at the feat. Lunch + four signatures in three aldeas in one afternoon.

Juana texts me that night: did you make it home? “Sí, gracias por todo amiga” I tell her. The next day she texts again: “When are you coming to visit Chomito?”

I should say that Peace Corps never felt like that before. I felt like how I imagined Peace Corps to be before I joined, which was on a mission trip, exploring the unknown, knocking on doors and being stared at. I felt lost in an adventurous sort of way, I felt like I was in a place that was totally quiet. I felt how I feel every time I get on an airplane and my identity gets shuffled between luggage, seat assignments and flight announcements. But this time I was steeped in complete foreignness in the essential sense of the word, and no chaos. Complete, pin drop + bird chirp, calm, draped in leaves.

I’ve been in service long enough to be lost, found and lost again, and that day I was both lost and found. I don’t need certainty, or familiarity, near as much as I long for welcome. And that’s why I left my unhappy, predictable life in the US, not to be known but to be welcomed. And as I have been extremely fortunate, to find and be found in rural Guatemala and to be invited again.