Today I walked out of my door to put my reusable grocery tote back in the car. Out fell the receipt from Walmart: whole milk yogurt, 4 avocados, and Whole B complex suggested by my doctor. Things a single woman buys at Walmart, I guess. I try not to litter but there was no salvaging it. It was beautiful: something I owned being able to be that free and unfettered and weightless. And my awareness immediately went to Irena in the prison who isn’t even as free as this flimsy, useless receipt that took off into the blue unknown carried by this unusually windy day.

It’s been eleven days since I met her and her face and her story weigh heavy on my conscience. She is one of thousands. Visitation lasts an hour and it’s open between 12-3pm at La Palma Prison in Eloy, Arizona.

Where the hell is Eloy, Arizona? Nowhere.

You can give a correctional center stars?

On Tuesday I spoke to a gentleman named Bob who drives up to the prisons on Mondays and Saturdays. I found out about this initiative through the Desert Doves meeting (a group of Return Peace Corps volunteers in Tucson). The imprisoned people send Bob letters. Since he goes weekly, his mailing address gets passed around between detainees and he brings paper to them so they can write. “They say they provide them envelopes and stamps but that’s not true” he said, as we drove up.

As a part of the Kino Border Initiative, people visit these two prisons between Phoenix and Tucson. That is it: visit. We don’t rescue anyone, or heal anyone or free anyone or help anyone (as if we could). We listen. In a way that could be helping, but how helpful would you feel sitting across from someone in a prison uniform and listening? Helpless would be just about how helpful you would feel. Still: you do it because it is the difference between having someone visit them that day or no one. It’s not nothing. So with my not-nothing effort, I made a plan to meet Bob with my friend Rebecca to go to the prison (full disclosure, I get community service hours for my Peace Corps assistantship for going). Here you can find pictures of the prison from the inside: Eloy Prison.

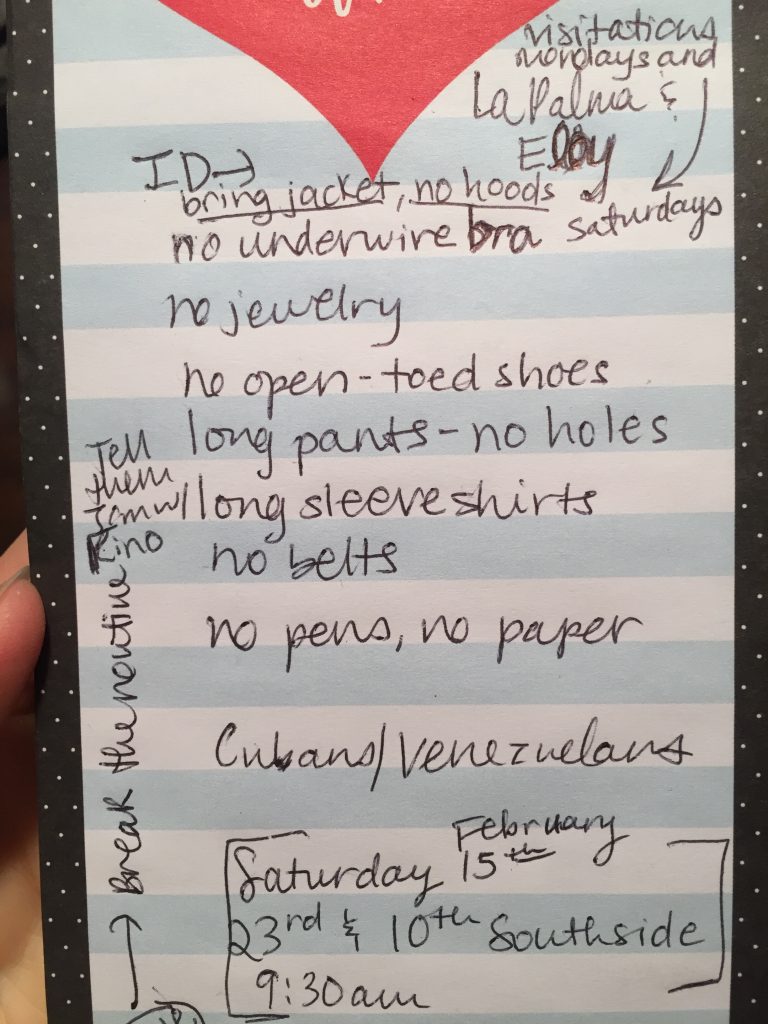

Bob said on the phone: bring only your ID and car keys. No underwire bra, no jewelry, no open-toed shoes, long pants with no holes, a sweatshirt with NO HOOD, no belts, no pens and no paper. “You’re going to want a sweater though. It’s cold in there.” When we pulled up to the parking lot of Southside Presbyterian, our meeting place, we waited. Several workers asked us if we needed labor: “No thank you, sorry!” I rolled down my window to say. Even that was a reminder of my privilege and the day hadn’t even started.

The sun beamed down on our car unrelentingly as Rebecca and I caught up about our lives and grad school as we waited for Bob. In ten minutes Bob pulled up in a 2000 Toyota Corolla. I only know the car facts because we had to write down the year, make and model on the prison visitation form. I also know that Bob spells Corolla with one l. Neither here nor there. (Let me take my language teacher hat off. I can’t wear a hat into the prison. I can’t even wear a normal bra into the prison).

We introduced ourselves. “We’re waiting on our fourth person” he said, so we talked in the sunshine. He thanked us for our interest and told us a bit more about the project and the purpose of going. He choked up when he remembered a specific detainee’s story: “Yes, some of them get sent home.”

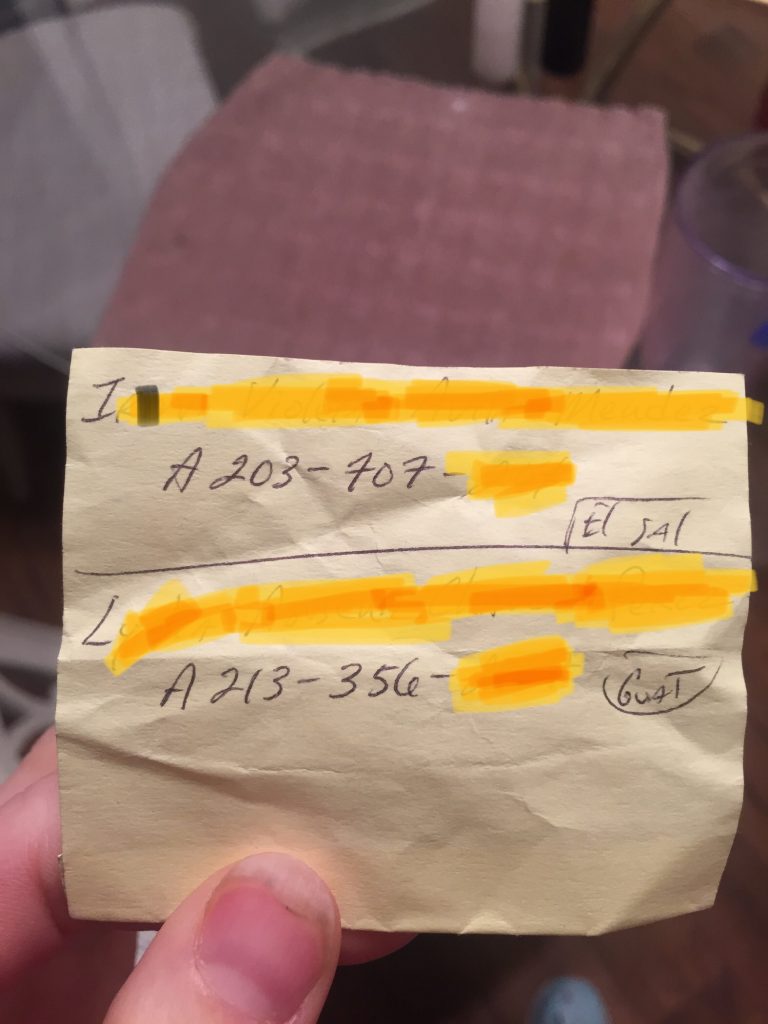

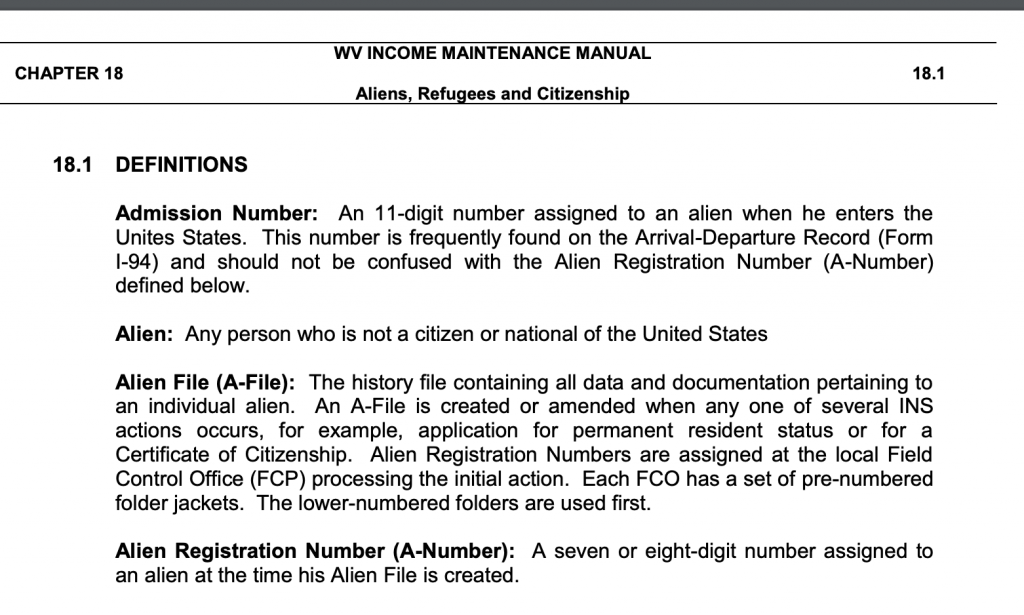

He handed us each a yellow post-it with two names written on each: “In case one of them is not there anymore. You can’t carry these in, they’ll make you throw them away. So you should memorize their last names.” On my paper he wrote “El Sal” and on the other “Guat” (with names and A-numbers by each, but I won’t mention them here). My heart fluttered to see the name of my home of 31 months on this paper. Do you know what the “A” stands for? Alien.

Irena (not her name) is from El Salvador and who I was to visit.

We had more questions than less to which we got answers but with more answers there are always more questions. Namely “Why?” If you think this short conversation put us at ease or gave us more clarity about what we were about to do, you’d be wrong.

Eventually Rebecca asked for their files while we waited. He handed us each a manila folder with the detainees’ names written on each who we would be visiting. They had their full names with A-numbers on the labeled tab. Last names first. I wonder how many file folders like this he had. Irena (who I would visit) had written him a 5-page letter earlier that week explaining her life story and asking for help. Eventually the 4th person in our group pulled onto the gravel parking lot. “Sorry, my yoga class ran late” and we took off for the uncertain to be made painfully clear.

The Arizona sky has a way of swallowing you whole. But so does a prison.

The car ride was quiet. I read Irena’s letter as we crossed over the desert. Irena wrote about walking through the desert, and we were driving across it in an air-conditioned car. I saw that her daughter’s name was mine. I usually get car-sick when I read but surprisingly I didn’t. I noticed how her e’s looked like a’s and that she wrote q’ for the word que. But how many hand-written letters have I read from a Spanish-speaker? This is the first. I did not recognize some of the words. I noticed the tenses they were written in. Imperfect subjunctive I thought. Damn subjunctive. I thought the letter was three pages until I saw each page was front and back. There were numbers on the top. How many times had she written her story in her head? Within the paragraphs were words you read in the news or a telenovela: “las pandillas” | “MS13” | “prostituta” | “se convertió en un hombre horrible” | “yo vivía en el infierno.”

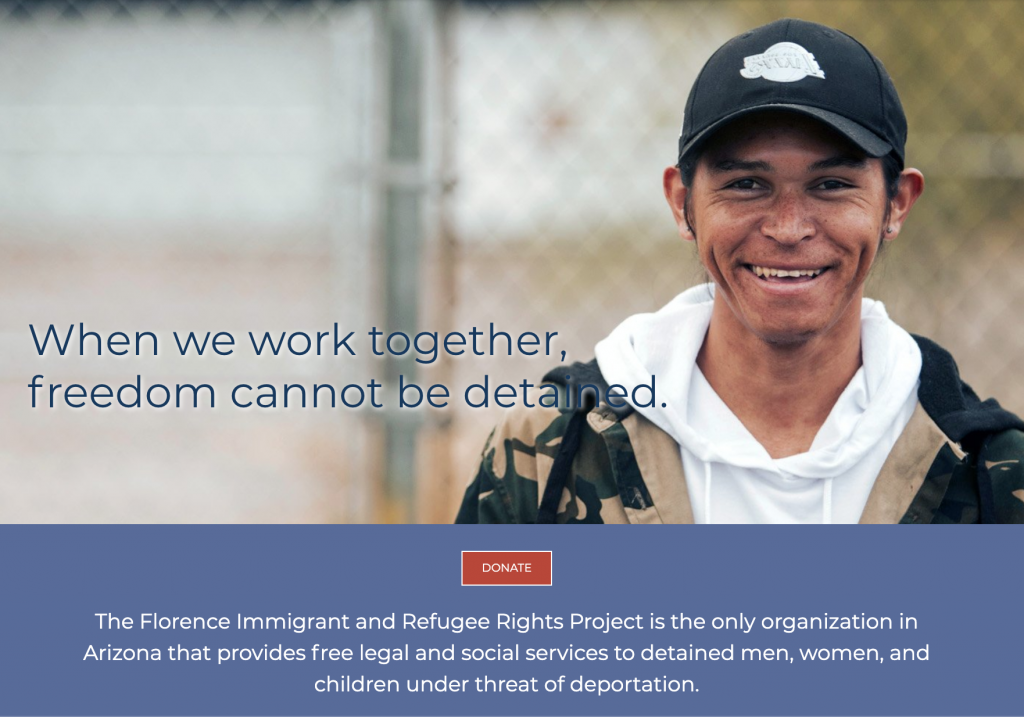

I asked Bob as we sped up the highway: “How can I help this woman? It says she knows nothing of the laws and, well, neither do I.” He said: “Tell her about the Florence Project that comes on Thursdays.” Okay. I tried to remember the name.

It took time but I finished the letter. At end she wrote: “Realmente estoy agradecida a mi Padre Celestial.” It made me think of my Host Mom in Guatemala who said: “Padre Celestial!” when she was surprised by something a la “Oh Dear God!”. This was a very different use of Padre Celestial (Heavenly Father). And she was writing about her gratitude to God from a prison cell.

After stopping for a bathroom break at a tourist spot in Picacho, we pulled onto the grounds of the prison. There were three distinct parking lots: Parking for prison officials, parking for law officials (attorneys, lawyers..) and parking for visitors. Guess which was furthest from the entrance? We left our things in the trunk and I checked my pockets to ensure they were empty. We followed the small stream of people forming to the entrance. It’s hard to say what I noticed first: the wire, the door, the buzzer or the whole thing. The colors were light blue and there was a big sign that said CIVIC CORE at the entrance. Advertising space for prison systems? There were more children than adults, and I naturally wondered what their connection was to everyone inside. Family probably. Saturday is family and friend visitation day. But perhaps a more sensible thing to wonder would be what connection I had to Irena. No connection at all.

The 4th person in our group pushed the button at a big, blue metal door. A muffled voice asked something and she responded calmly: “Friend Visit.” I filed that away. We walked to the second door and waited. We were between doors and under a sea of wires and probably enough cameras to count the pores on our faces. She pushed the second button. Eventually a buzzing sound emanated from the door and we pushed our way through.

We walked inside a room with a window that was covered with a metallic sheen that showed our reflection. We quickly and quietly began to fill out the visitation form after we took a ticket. You know, the type of ticket you pull at IKEA when you are waiting to make a return. Mine was J38. If “A” stands for Alien, what does “J” stand for? It doesn’t stand for anything, it’s just my place in line. The alphabet is kinder to me.

There were two visitation form options: English and Spanish. The form was confusing: was I the visitor? I messed up, started over. I wrote the A-number down with Irena’s full name. And then I remembered that I left the only thing I was supposed to bring in Bob’s car: my ID. The ticket numbers were flashing on the screen and it was already up to J34. Bob silently slid his keys over to me and I ran back outside, pushing both buttons at both doors and waiting, and trying to push it too quickly and waiting and finally getting through.

I ran to the furthest parking lot, grabbed my ID and ran back. J38, J38. I looked up at the winding concertina wire that adorns prisons like Christmas lights of terror. Harrowing. Does it keep anyone in or is it simply fear-mongering? How do prison designers rate their job satisfaction? Very Satisfied? Javert in Les Mis? Or is it just a job? I pushed the button and waited again: “Friend visit” I said to the muffled voice and hoped it would work. I heard the magnetic buzz.

I walked back inside the prison, walked past my reflection and J38 had far been passed. I asked: “Do I need another number?” She took my ID, handed me a plastic bin like in airport security and said: “take off your shoes and jacket.” I guess I didn’t need a new number. She wore those permanent fake eyelashes like my students wear. She was multi-tasking like a champ. She was used to doing this, I think. Two visitors: a young girl and guy were asking her: “My Mom’s glasses broke. Can I bring her these?” “No” the guard with the fake eyelashes said. “Okay and can I bring her this money?” She had envelopes from the bank in hand. “No” repeated eyelashes. “Okay” said the girl.

Okay.

I thought of my host family when they say: “¿Qué podemos hacer? No podemos hacer nada.” Okay is the shorter version.

I removed my shoes and sweater and walked through the sensor. Eyelashes came over to pat me down, all pleasant and friendly. I wonder if she patted me less because I am white. Bob was waiting on the other side and I handed him his keys. He said: “One time a lady came to do a visitation with me who had metal rods in her back. They wouldn’t let her in.” What was she going to do? I wondered. Use her back as a weapon?

I walked into a waiting room with a TV attached to the wall and two vending machines. I sat down next to Rebecca on strange plastic couches filled with air and the colors of shy Easter, springy like the floor of a playground made out of recycled tires. “Must be easy to wipe down” Rebecca commented. I woud have taken pictures of this room discreetly except we couldn’t bring anything in. I’m surprised the post-it was still in my pocket.

The sign on the TV said “DO NOT CHANGE THE VOLUME.” A woman with three children sat to our left and just behind us with three small children crawling on her: “are they twins?” “No” she said. I smiled at them both. This felt like a hospital waiting room, and the refugees are about as guilty for being locked up as the people in hospitals are for being sick. The Mom of the three kids took to singing “The Wheels on the Bus go ‘round and ‘round.” What a terrible song to have in your head when you’re in a prison where all you have are wheels: ‘round and ‘round. ‘round and ‘round. All through your mind.

Bob walked up to us again: “You will walk into a room and you won’t know who you are visiting. In that case it is okay to ask.” I filed that away. I wasn’t nervous but I wasn’t calm.

Bailey and Bob, two from our group, heard the last names of the detainees called out over the noise of the TV and walked up to a door. Then it was just Rebecca and me and all of the other parents with children and family members waiting. We sat on the unfamiliar couches and took in the space. We shared how uncertain we felt about this visit, we evaluated our privilege and talked about White Saviorism and how this factored into this experience. She heard her detainee’s last name called and quickly got up and walked to the same door. She pushed the button and waited.

And then, it was me. I sat in a room of people I didn’t know and I felt the absence of my cell phone locked away in the trunk of Bob’s car. I stowed my hands in my pockets, what else could I do with them? I heard the detainee’s name (who I was to visit) and stood up. “No, not you” said eyelashes. And I said “Oh” turning back. I sat down on a closer couch. It was hard to hear over the TV.

Another 10 minutes passed and I regretted forgetting my ID. A guy to my right asked: “Is this your first time?” “Yes” I said. He was with the girl who brought the glasses for her mom. They called the last name “Patel” and the two stood up. I wondered if the detainee was from India based on the last name, but this is nothing more than an assumption. Still, I was surprised and didn’t expect that. I imagined their Mom inside.

The movie ended and eyelashes asked the other guard: “What movie should we put on now? We can do Frozen or Cars.” Eventually I heard my detainee’s last name called again and I stood up. I checked the post-it note in my pocket again. Eyelashes didn’t take it during the pat down, though Bob said she would. I was relieved to have it but I don’t know why.

I headed up a line of people forming behind me to walk in to the visitation room. I pressed the button, I waited. I was pressing so many buttons today. Then we walked into a room with two more doors to choose from. I didn’t know which one was the right one. I turned around for reassurance. You don’t want to open the wrong door in prison. Eventually I chose the door with all of the people. I walked in and saw Rebecca out of my periphery talking to someone at a table.

The room was narrow with white plastic tables where people sat across from each other. A 6-inch tall divider ran across the tops of each table. We would not be separated by glass like you see on TV but a 6-inch piece of wood that suggested the barrier that existed between us, as if the doors and A-number weren’t enough. I pulled out my post-it note to look at the name: “You can’t give her anything, what are you doing?” a blonde security guard said to me. “I am not, I just wanted to remember her name.” She said: “Okay who are you here to see?” I handed her the visitation form and she pointed to a woman I did not recognize.

I walked up to Irena and she stood up out of the chair. Her handwriting flashed through my mind: “Soy Irena. Tengo 39 años de edad y soy de El Salvador.” She was uncertain. I offered her a hug. This would be the only chance for us to touch so I knew I had to do it now even though it was uncomfortable and maybe awkward for her. “Hola Soy Natalia. Sé que su hija se llama Natalia también.” She was confused: “Está usted de Kino?” And I said: “Sí estoy de Kino.” She knew that “El Proyecto Kino” is who she wrote the letter to. “To someone who might care” might as well have been who she addressed it to for all she knew. She is in a big, foreign country alone.

I pulled out the chair across from her and quickly sat. We looked at each other from over the divider. She was not sure where to start, nor I. Her prison uniform was hunter green. I was relieved it wasn’t orange or khaki. I don’t know why I was relieved by this or by anything. As I put together language in Spanish I was reminded of several things: I have to use usted. I tell my students everyday: “you use usted when you talk to me as a sign of respect.” Spanish is not my first language and I’m not even sure if Spanish was my first language, that I would feel anymore comfortable visiting a stranger in prison. I told her that I read her letter. “How are you doing?” didn’t seem like a fitting follow-up statement.

Everyday in my Spanish class, the students complete the date: “Hoy es miércoles, 13 de febrero de 2,020. Ayer fue martes y mañana será jueves.” Every. single. day. What must it be like for her to think that every day? “Yesterday was Tuesday, tomorrow will be Thursday. Today is Wednesday: will the judge give me mercy?” So we started where a person starts: with the most recent thing. She told me that the judge said that he would not accept her plea for asylum, and that was last Wednesday. I saw the sense of doom at the base of her irises like anvils. I couldn’t hear her very well as she started to explain the next time she will go to court, and why. I told her how sorry I was, and I also had to explain as I saw her eyes seeking some sort of answer in mine that I did not have the answers, and I did not understand the system, but that I felt terribly sorry and that I believed that she was going to get out of there.

The plastic divider hadn’t budged an inch.

We continued backwards in time to what came before court: how she got here. She continued to speak in hushed tones. I leaned as close to the divider as I could. I knew I couldn’t touch her while we sat, Bob told me the guards would say something. I began to wonder if someone was timing us. I knew we had an hour but I didn’t know how they were keeping track because I didn’t come in at the same time as everyone else. My mind wasn’t on the time, but rather, who and how I was being controlled: how she must feel everyday. She was so lost, so pained and desperate for hope or help. She was so pained by her life story that I didn’t dare ask her to repeat herself even though it was difficult to understand her.

She explained that she started out from El Salvador with a coyote (coyotes are people who get paid to help immigrants cross without papers. They have relationships with the gangs who control parts of the border and they can get people across. They often take the steep fee that is paid them and abandon the people they are meant to take somewhere early on in the journey). “7 days I walked in the desert alone” she told me. She pulled her hands to her face as she spoke. “By the time we got to (name I can’t remember), I got held up in Mexico and I told the men who wanted money from me that I didn’t have anything. He said he would kill me if I didn’t give him what I had. He found the money and took the last of what I had. It wasn’t much, but it was all the money I had left.” “Was it stashed in your bra?” I felt I could ask her that and I don’t know why. She told me yes and then she said that he touched her there and everywhere against her will. “Por todas partes” were her words.

“I continued on” she said. “The next place I got to, I slept on the floor and it was so crowded there. It was like a shelter. We waited at the entry point at (name I can’t remember) and when we were sent through, we crossed as a group of 25. Then I stayed in a home there for 20 days and they were very nice. Then when I was almost to the point where I was told there was a shelter that would help me, la migra caught me on the way. La migra is ICE: Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

I read a book last year called Solito, Solita and it told many of these terrible border crossing stories. The puzzle pieces of her story were familiar because drugs and gang violence reduce us to different stories with all of the same chapters. You know how bad someone’s conditions are when they make it a point to tell you: “He gave me water.”

About the border patrol, she said: “Some of the guards were nice, and some of them were not human. No son humanos. I begged the man not to throw my small Bible away that I always kept with me. But he threw it away. It made it all the way with me and it was all I had left, and then he took it from me and threw it away.”

In that moment I said: “Your fingernails are so beautiful. Look at mine: I am no model and look at yours! They are perfect!” And I am not kidding when I say, they looked so perfect I thought they were fake. She crossed the desert by herself. She said: “No, you’re so beautiful!” (We were having a pageant-off in prison). And this is the time when I used my line I always used in Guatemala: “Nadie me quiere, ni siquiera mi gato!” I knew we both needed this laugh, and laugh we did. I took a risk by referring to something frivolous. I’m glad it made her laugh.

Then she went further back in time: her home and the events that led up to her departure. It was everything I read in her letter but instead of reading her handwriting, I was reading her eyes. I took in every angle of her face and every word in Spanish and tried to absorb it. It was all I could do.

Before her home became unlivable, her life was good. Her eyes lit up when she talked about her children, and she explained what her ex-husband was like before he became the person who destroyed her life. She told me details that were surprising for a stranger to offer. I don’t want to share the details here, because it is her story to tell. But it felt almost like we were old friends.

The gang members were threatening her for her life and she knew there was no where else she could go but to leave the country. When she made that decision, she said that she could not wake her children up to tell them goodbye. If she woke them up she would never leave. She said: “All I can remember is how my daughter looked as she slept.” She pulled her hands to her face. My eyes welled up. I didn’t cry until then.

She told me about her two children and who is caring for them now (her Mom). She told me that her son was the most thoughtful person ever, but that her daughter was not that way at all: she was selfish. I laughed and said: “She sounds like me!” (Don’t ask my Mom for stories, please). We laughed and we laughed loud. We needed to laugh. Her children were her only pride and joy. If the guards had told me to stop laughing, I would have only laughed louder. That’s not true because I would peed my pants but I like to tell myself I would have laughed anyway.

She said: “I don’t know the laws. And I never thought I’d end up here. My life is in the hands of a man I have never met. The judge.”

I told her to look out for the group that comes on Thursdays to help. She said: “A man came once and told me he would help me. He told me that my family had to pay him $1500 so we found the money to pay him. He came for 30 minutes with a translator and left. He never came back.” I told her that she needs to look out for the Thursday people. I could not remember what their names were, but I filed away that story about the lawyer because I wanted to ask Bob. Who was that guy?

And we both sat in this horrible circumstance together: except I get to leave. I looked at her and said: “You are not going to be here forever. And when you do get out of here, you are never going to forget how much you suffered and how grateful you are not to be here anymore.”

She looked at me with conviction and said: “Oh, Natalie, there are people who complain about the sun, who complain about the wind. I will never, ever forget how grateful I am to be free when I am free again.” And when I get out of here, she said, I want to help people the way that you are helping me. And that hit me like a ton of bricks. How could she think of anyone else except herself? I wouldn’t be that generous, not when I was locked up for trying to escape a violent country.

Irena never cursed once. She even said: “Truthfully I am grateful. I have a place to sleep and something to eat, but I am not free.” She is not free. Not even as free as the trash on the street that moves with the wind.

I asked: “¿Qué le da de comer?” She said: “Papas y pan.” Potatoes and bread. “A veces no lo como porque no tiene nada de sabor.” I vowed to myself to be grateful for all of the food in my pantry. And then we talked about her room. She told me there were bunkbeds and she slept on the top, and that her roommate from Venezuela was very nice and always read the Bible to her.

“Sometimes I get panic attacks. But my roommate tells me to calm down and reads the Bible to me. She is the only good one. The others can be horrible.”

And she got sad again: “There are many days when I don’t want to get out of bed. And I remember my children and how they are the only reason I keep going. I am not with them, but at least I know that they are with my Mom. I get to talk to them sometimes.”

The darkness crept into her face. She wondered if she would be better off dead.

She heaved a heavy sigh: “Well, at least I know that I got to see you today, and talk to someone. There isn’t anyone to talk to. It helps a little bit to tell someone else everything that is happening to me.” I think she was trying to prepare herself into going back to a cell again. Indefinitely.

I told her I would think of her, and that I would ask my Dad to add her to the prayer list at the church. I knew our time was coming to an end, and when I heard the guard call out her last name, I knew that our time was up. I guess they were keeping time. I got up to hug her and I was very nervous the guard would swat me away. I said: “Se cuida mucho” (which I don’t think she has much control over at all) and I walked away. I almost said: “Te veo pronto” like I do to my mentor teacher every day, but I can’t say that. I am not sure I will see her again. I turned back and waved at her twice. She smiled. I walked out and waited for the second door to buzz me out. I gave the guard my badge and waited for my ID back.

Eyelashes was eating lunch. It wasn’t potatoes and bread. I did the button/door routine outside again and finally I was free of those doors. That makes one of us.

The ride home was filled with more questions: what happens when they get bond versus asylum? Fianza is bond in Spanish (I learned). ICE tracker is a website where you can find out where the detainees are by way of their a-numbers. You can send them money in the mail, and books through Amazon prime. They take the cash out of the letters and put it onto their account. But you cannot send them pencils or anything else. Amazon prime drives into prisons? Oh yeah, and that lawyer who took $1500 of her families’ money? Those types run through the prisons all the time and take the detainees money with no intention of helping them.

“It’s more relaxed on Mondays” he said. “That’s probably because Mondays are not for family visits but for professionals like lawyers. The prison is much kinder on those days and so are the guards.” “Why Eloy?” we asked, assuming costs are lower in the middle of nowhere. He said: “Yes, costs are lower and also: out of sight, out of mind.” So society at large doesn’t have to consider what we’re doing to people fleeing their lives: locking them up and giving them potatoes.

And as I say that, I want to remind myself of these things by writing them down: My frustrating relationships with coworkers is not a life or death situation. My car troubles are just that: troubles. And my draining job is a job I’m lucky to have.

My heart is heavy with her story. And the question as to what a visit really did for her. And why life is so thoroughly cruel to some people and has been so gracious to me.

If you feel the inclination to sing my praises, please instead think of something you can do to help and do it. I am not being down on myself but this post is about spreading awareness about the importance of empathy for these people who have to flee from their homes. We have to try, poco a poco, with a book purchase on Amazon Prime or a letter with 5 dollars cash. Or just a reminder how lucky we are and how much we need to help; Treat others as you would want to be treated. Go to ICE Tracker and try for A-numbers until you find someone to send money in the mail. They get a sample size of shampoo/body wash-in-one, one packet a week, to last them for both body wash and shampoo. Send them a couple of 5s, they can take the money and buy themselves something other than potatoes as they wait for our country to decide if they will have mercy on them or send them back to the dangerous, unlivable conditions they came from.

Today is day 11 of my confinement due covid-19 pandemic. After reading Natalie’s piece about visiting an asylum seeker in Eloy, I realize that, by comparison, I am free as a bird. And I am above all, grateful.