Foreigner Alphabet is a series of posts inspired by The 75 Palabras in Guatemala Series. It is not a real alphabet, it’s a series of words organized by their first letter and inspired by the experience of being foreign in a beautiful place, Guatemala, for two years of service in the Peace Corps.

Ρ

P! Would have been a B if it hadn’t given up so soon. P seems a semanal addition to the Guatemalan Spanish alphabet because so many Chapín [nickname for Guatemalan] words start with P.

“No podemos comprar porque no tenemos pisto” my host mom said with a chuckle.

Pisto:

Slang for dinero. “We don’t have cash so we can’t buy anything for her birthday.” In K’iche’ pisto is puac (pwock). Maj puac ‘no hay dinero.’ But, people in the village think I have puac and there is a gesture for that: you hold your two fingers up like a wad of folded-up cash is pinned in between. In Mexico, I hear, the slang version of dinero is not pisto but plata (silver). Either way, I regularly refer to pisto or puac in the streets when I am bargaining. I say: “Piensas que hay dinero pero maj puac.” I don’t know if it serves in getting the price down but it does make them laugh. Maybe our equivalent in the States is being loaded? Why is it a gun-related word, I wonder? Only too relevant given the state of affairs in my country around the issue of gun control.

A store owner in my site once told me that people who have money talk about it like they don’t have it, but people without money don’t talk about money. I wonder if that’s true? From my personal experience in the States, I crinkled up over money and I think I still do. But I wonder if that is because I grew up thinking of everything in terms of it’s dollar value instead of practical value. I don’t know, really. But it’s interesting how much money gets nicknamed across cultures. It’s paper but it has so much influence because of the power it’s been given.

Pisto, puac, dinero.

Pueblo:

It’s really sweet because when people ask where I am from, I tell them “The States” and they say: “Sí pero que pueblo..?” and it always catches me off guard. They never say “pero que ciudad?” They also say “pero qué pueblo?” o “pero dónde está su casa…?” Weird to describe the interstate spaghetti dish that is Atlanta as mi casa. What’s the equivalent of pueblo in the States? Drive-by town? One-light town? Small town? BFE? In Europe some folks call small towns villages which is a term we don’t really use in the States either: unless we’re talking about Beauty and the Beast or colonial times.

But when I talk about Santa Clara to other Guatemalans I call it a “pueblito” because that’s what it is. It’s small (population of 14,000 if you include the aldeas, the rural villages outside of the pueblo) rural community with earnest, hardworking folk, a town hall with various offices and a plaza which is home to the Tuesday and Saturday market, events center and epicenter of small town chisme [gossip].

Probando, Probando. Uno Dos. Uno Dos.

Probando Sonido:

Probando Sonido is our Testing, Testing 1-2-3, Testing.

What would a lecture, publicity, business or anything official be without a microphone in this country? I don’t know about everywhere in Guatemala, but in Santa Clara Sound is King. The thing that amuses me about it is how serious having sound is. Probando, Probando, One, Two. Their palm fully wrapped around half of the mic to amplify their voices and make them sound more like a deity. (I’ve never heard a woman test sound on a microphone in Santa Clara).

I wonder if it comes from this: sound equipment is heavy (only men can carry heavy things, obviously) and sound is power so sound is a man’s job [I’m assuming?] Also, sound in the campo is not installed permanently for the chance that it could be stolen and it’s need to be moved from the gym to the classroom to the salon de charlas.

I pass traveling salesmen doing demonstration/pitches on market days who wear wired mics, and by wired, I mean a coat-hanger has been fashioned into a mic-holder propped on their chest. I respect their ingenuity but I also wonder if their products are any good. Classic lack-of-trust for all salespeople has been instilled in me since forever (don’t take my pisto). These market sales-guys are a lot like in-person Vince Offer (the Shamwow Guy) or Billy Mays (Oxy Clean) may he rest in peace. But rarely do I notice people selling cleaning products, they are selling cures. I think health still has elements of the mystical here because science has not pervaded beliefs about illnesses and cures. So the sales people can really gather a crowd, the more likely people are to buy because health still has mysterious components.

Probando, Probando, Uno Dos Uno Dos.

When my site organized an overnight camp last December, I knew SOUND IS IMPORTANT for a room about 5 yards wide and 12 yards deep, we HAD to have a sound system with a sound board. Not simply a mic connected to a speaker but channels and buttons and the whole bit. For a small room where I rarely if at all used a mic, the technician from the Health Center and the Youth Protection Director interrupted one of our youth leaders teaching a session with “Probando Probando Sonido” because SOUND was more important than what the young facilitator was actually saying.Myself and the other volunteer looked at each other like: “Are they serious right now?” And yes, yes they were serious because sound is serious.

If you hear Probando, the event is about to start (30-40 minutes after the advertised time).

Do we need speakers for the event? Occasionally Sometimes Half of the Time Always ABSOLUTELY ALWAYS

But I don’t think I’m making my point adequately: Small corner fried-chicken shops hire guys with speakers and mics to advertise their businesses. Music plays all day with a DJ lowering the sound to advertise ofertas, say hello to passersby and promote the Fried Chicken Business all around the small pueblo. It makes me chuckle every time I pass by because the guy is just sitting there in the sunshine carrying on about fried chicken over the sound of cumbia.

Picante:

At every Guatemalan table (at which I have sat) there is chile as a condiment. But it may not be the picante that you imagine: not the hot, sweat on your brow or above your lip caught in your would-be-mustache-hairs heat. I’d say most Guatemalans are moderate about their chile use or don’t like chile at all. But still, at every restaurant or at every table, there is a tiny bowl with chili sauce usually accompanied by a small spoon so you can relinquish a few drops atop your grub.

Before Guatemala I did not eat much chile. But I don’t like for my food to be bland, and I am one to aprovechar/take advantage of the consumables in front of me. So chile has thusly entered my routine and palate. I will surely take this with me when I leave.

There are only a few hot chiles in Guatemala that I know: chiltepe, Santo Domingo and jalapeño. They prepare the chile differently than some. They actually boil carrot slices, onion and cabbage with jalapeño and those vegetables become infused with the sweet kick of picante. Oh also there is ‘chile seco’ which is dried chile a shade of crucible red.

Now: Why has this made the alphabet? First of all because it is a part of my daily life and because I like the use of the word picante in Spanish.

You don’t describe ‘chile’ as HOT like they do on taco bell packets. No sir. Chile is referred to as Picante and the word picante means ‘biting.’ So when fleas or whatever these mysterious animals are which feast on me like I’m leftover chicken, they leave bites which pica/sting. I like that there is a collaboration between bites and chiles: eating and being eaten, literally. When I have a bite I complain “pero como piiiiica” and my family pities me. Why do I get bitten and they do not? It’s a Peace Corps Murder She Wrote mystery never to be solved.

Picamás is my favorite chile brand because it’s A: cheap and B: flavorful. It is based in the powerful but tiny chiltepe, a fraction of the size of a green grape but bigger than a crumb. How do you prepare chile in the campo? First you wash the chile (soap and water if you’re smart) then you place the dried chile on the surface of the wood-burning stove. (Oh: they sell these chiles in the market in clear, plastic bags in varying quantities. They weight next to nothing and charge by the ounce. I’ve never seen them growing out in nature in Santa Clara but I did see them once in Antigua at a coffee farm). The heat coming up from the flames makes the chile dance. Eventually, the chile shows signs of browning on the tough, green skin and you place them in an earthen bowl and grab a wooden machucador/masher and smash the suckers ’til they look like dead bugs (sorry but true). Then you add a few drips of water, stir it up and you have a basic chile sauce. Seems simple but I never knew this before coming here. I’m sure you can blend a bunch of ingredients to make amazing, flavorful sauces. Maybe someday when I live in a modern kitchen I will do just that. But for now, my host family and I always prepare chile as such.

In the start of year two I met a new chile with an incredible flavor! It’s a dried red pepper called ‘chile seco.’ I wash it, let it brown slowly over the edge of the plancha (but not the center of the plancha where it’s too hot or it burns). After the chile hardens from drying out, you pluck off the stem and shake all the seeds out. Then set it in the earthen bowl and repeat. I can buy an ounce of chile for Q2 (in other words: cheap). They sell them in the market in baskets and send me away with a small bag.

Pero con cuidado porque pica. Another reason why women wear delantales/aprons, so they can wipe their noses.

Permiso:

Con Permiso literally means With Permission, but I love how idiosyncratic it is to the culture of Guatemala. When you enter a house, even though the guest has invited you in, you say “Permiso” when you cross the threshold. All of the students in my básicos where I work (middle schools) say “Permiso” when they walk in and out of any classroom, or the principal’s office. It’s integral to entering or exiting a room.

It may be difficult to work with the básico students because they don’t listen. And while that is a major sign of disrespect in the US, no one in the States asks for permission to enter a room, which would be a major sign of disrespect here.

Pan:

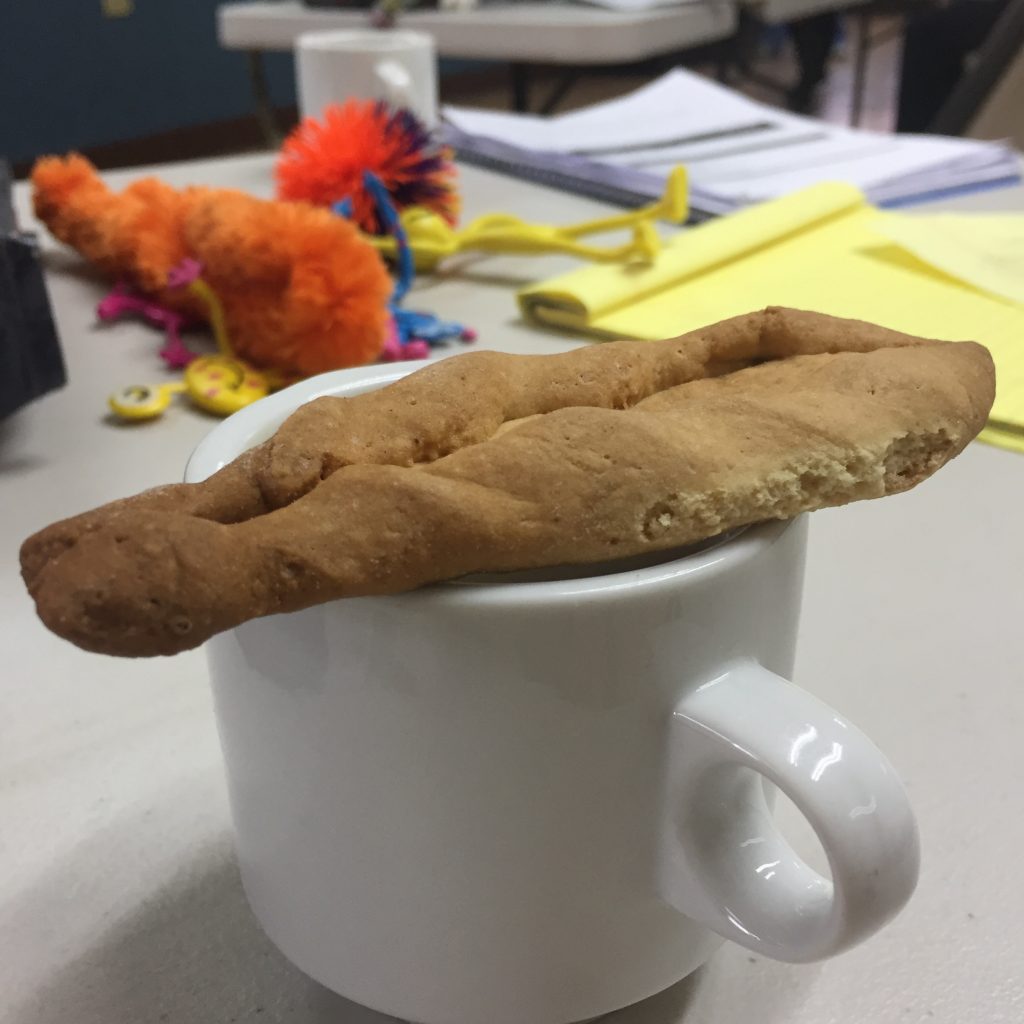

Pan is bread and it is what families offer you, along with coffee, when you stop by for a visit. Pan y café, pan y café. But don’t you dare eat pan alone. And don’t you dare drink coffee accompanied. The two go together, after dinner: pan y café. Wheat bread hardly exists in the campo, white, sweat bread or floury butter bread. During the week of Easter, everyone eats Pan that’s elaborately baked with designs atop. You sit with your coffee in hand and eat your pan, slowly, as you chat and enjoy company.

Provecho:

And quite possibly my favorite P, Provecho!

Buen Provecho, good provision literally translated, is what people say to you after you finish a meal. You finish eating and when you are done, you look to everyone purposefully and say: “Muchas Gracias” and they say “Buen Provecho!” It’s like Bon Appétit but AFTER the meal is over. And when you look up the equivalent of Buen Provecho in English, Bon Appétit is the translation. Which just goes to show you we need to be more purposeful and grateful for our food in the US and the company it brings us. Pues, in my humble opinion.

Muchas Gracias for reading! [Buen Provecho] 🙂