So I made it through July and August, the absolute armpit of this year, and maybe my service. Close to something important (like Close of Service), but not there yet. The desert of work. The monotony of teaching classes to disinterested, rambunctious teenagers, myself not even equaling an afterthought because that requires some recognition of my humanity, even if delayed.

I finished camp in June, a big undertaking, and after I had to take a moment to recalibrate. I had a ton to do before camp and once I finished the grant completion report after camp, I had about half the workload as before. Back to normal class schedule, rolling up my posters, my teaching ‘briefcase,’ umbrella, toilet paper, purse, water bottle, bidding Abuelita goodbye and walking to the normal rambunctious classroom to which neither bark or bite responds. My students spent the majority of July and August in preparation for Féria, the time of year that celebrates our Patron Saint: Santa Clara de Asís. I think some volunteers like Féria, I am not among them. Féria is a hurdle between me and doing my charlas. Mostly because of band practice. In rural Guatemala, you have band practice during and in place of class. Middle schoolers only study from 1-6pm as it is, so imagine my shock when they miss 2 of those 5 hours because they are playing musical instruments, terribly. And while I am teaching my charlas to the remaining non-band students, the instruments are mere feet from the classroom window drowning out any attempt at getting through their ears.

My friend read my posts from early 2018 and said: “I’m so sorry you were so sad in March and April…” I didn’t realize that I had been sad. Perhaps bored, tired, and at the start of researching the future (anxious!), but I don’t remember being terribly sad. However, I think about it now, and the realities of my privilege kept sinking in every day more and more thoroughly to my core and work was at a steady, tiring kick. So yes, maybe I was sad.

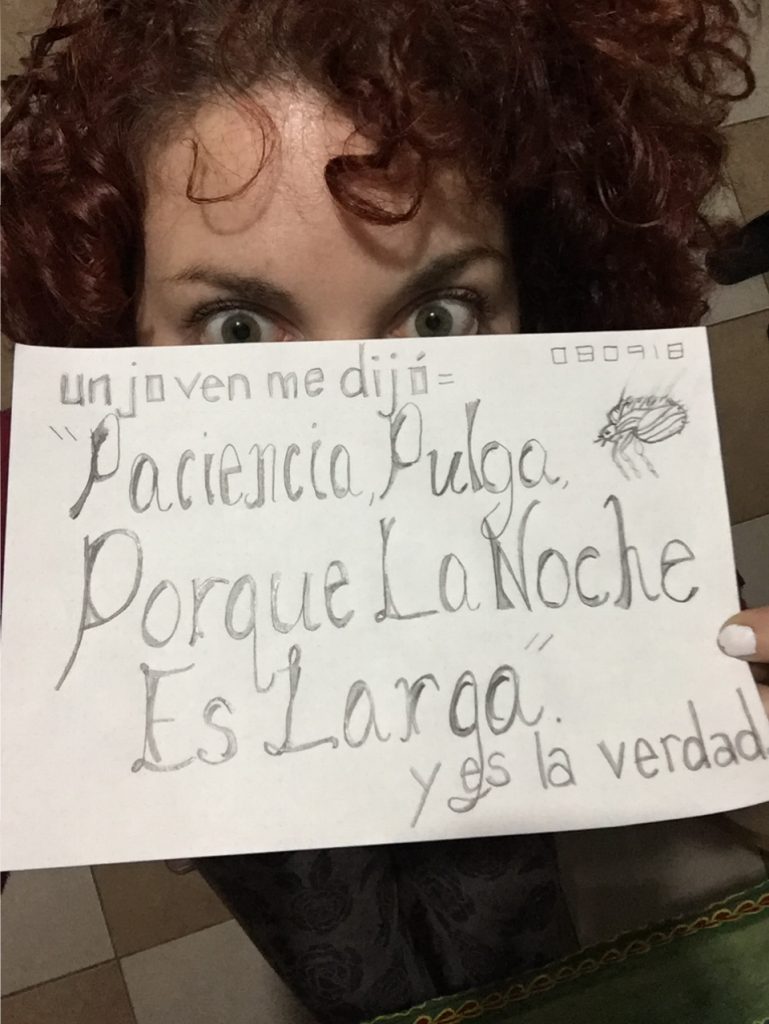

After those months was the jubilation of féria prep that I just described during which I felt feverish and stuck, which caused me to be very irritated. This annoyance came about because A: working with youth is, at the heart of it, irritating. But making decisions about my future make me anxious and pessimistic: a defense mechanism for things not working out in my favor. But still lodged so far from the end of service, I couldn’t make decisions yet, couldn’t apply for grad school yet, couldn’t make plans to go home for Christmas. Just had to wait until time passed for me to make my decisions.

So I got through it: I decided Yes, I will try to go to grad school. Yes, I will extend. These two decisions were like pancakes and syrup, one didn’t make sense without the other. And I had to pick both at once. So I applied for the extension, I told my parents I would stay longer to which my dad replied: “Natalie, you are gonna be 33 and not married when you get back here..” To which I have formulated the response: So was Jesus.

In the midst of these decisions, I decided to go home and surprise my sister for her 30th birthday. Going home is always a tightrope of pros and cons, and the comfort and culture shock that sneaks up on you like acid reflux can put a wrench in your pueblo homeostasis, knock you right off your delicate balance of foreigner in foreign land, eggs, more eggs, and tortillas, and put a hurdle in service. But my visit was short and I didn’t regret any second of it. I surprised my sister, saw my family, saw my Niece-Dog, friends, and came right back to country. The wild ride of flying standby was an adventure in and of itself but the visit was coming up for a gulp of fresh air and diving back into the the foreign current of the sea.

To go home, I made the decision to fly standby graciously offered by my long-time friend Marguerite. In doing so I tangoed with the fate of being stuck in Guatemala City for a night (which is strictly prohibited by Peace Corps Security). The night before my flight, I was supposed to go to Panajachel. Pana is a tourist town two hours from my site. It has a shuttle which leaves promptly at 5am and takes me to the airport. But…. I missed the last bus from Santa Clara to my site. In haste I rolled my heavy suitcase over the uneven streets and grabbed a tuk-tuk to see if I could still catch up with the bus. When we reached the end of the the tuk-tuk’s territory, it was me, the driver, and my heavy-ass suitcase full of heavy things to bring home.

I paid him Q3, descended the tuk-tuk and crossed the street to get out of the intersection. I had no plan. But it occurred to me that my friend, Gladys, lived right where I was standing (if memory served me right). I called her and sure enough, she walked outside to greet me. As it started to rain, she helped me carry my bag inside. “How did you know I lived here?” she asked, surprised. “Remember that one time I picked you up on the way to that training…” She did, and seemed surprised and delighted that I remembered. I am surprised because I never have my bearings.

I explained to her my situation: “How am I going to reach my 5am shuttle?” She responded “Well I am taking a 4:30am bus to the capital in the morning. Why don’t you leave your bag here, and in the morning, we will ride together to where you meet your shuttle?” My mess was being divinely mended. My bag heavy with mementos of Guatemala, I opted to leave it with Gladys. After asking her for reassurance: “You are sure the bus comes at 4:30? Not 5?” She promised. Buses can’t be promised in Guatemala. What if there is a cow in the road? Construction? A fallen tree, mudslide, the bus driver died the night before? Still, I walked uphill from Xiprian to the arco of Santa Clara and back to my house to knock, pathetically, on our side door. “Seño” I whimpered. Bagless, not on my way to Pana. “Que le pasó?” My host sister took me in, alarmed, confused. “I missed the bus…” We commenced the back and forth of deciding what I should do as we sat next to the stove in the kitchen: “What if your friend doesn’t wake up and you can’t get your bag?” “What if the bus doesn’t get here at 4:30?” “Should we just go get your bag now, to be sure?” “Well, if she doesn’t wake up, you can always take the public buses to the capital.” “But Peace Corps strictly prohibits that..” (the danger on buses in Guatemala City are very real). “Then you would have to take a taxi from Guatemala City to the airport,” Clara said. I called Gladys once more. “Are you sure you are going to wake up?” Yes, she promises me. That’s why I asked you when you were at my house: ‘Do you trust me?’” Like Aladdin. And I do. I called the shuttle company, told them I wouldn’t be leaving from Pana but would instead meet them at another stop, I reassured my host family everything would work out, hoping for that myself, and I went to bed. No one in my family in the US knew I was coming: only my brother-in-law. To everyone else, it would be a surprise. And at this point, I would be just as surprised if I made it, too.

At 3:45am I heard the metal door squeak open on the first floor, my host angels ready to accompany me to my bus. As we walked out the door, I couldn’t be bothered to unearth a sweater from my suitcase and later regretted it, my host Mom said: “Voy a llevar mi palo para los bolos y los chuchos” I died laughing: You are bringing a stick for the dogs and the drunks? “Pues sí” she said, unapologetically. A woman has to protect herself and machismo and stray dogs are not kind. The three of us perched up at the bus stop, me trying not to shiver, and I was amazed at the amount of life I saw in the streets at 4am. Men gathered at bus stops, waiting for their commute to the city. A man appeared with his camioneta to Xela. I couldn’t take that bus, going the wrong direction. My Host mom and Host sister explained every human being in our general vicinity. “That man, Natalie, he has been driving that bus for years. He was one of the first people to buy a camioneta and drive to Xela everyday..” When a suspect man cape up the hill, they whispered to each other in K’iche’: “Is he a drunk?” “Oh no, he’s just staggering a little.” My host mom held tightly to her guard stick. While we waited in doubt of the coming bus, Clara and Rosario recounted all the times that they would come to this bus stop over the years, sending Clara back to the capital to work. Back to her job. Her mom would always come with her to the bus stop, no matter how early. How sweet. Now they are accompanying me to the bus stop. I am an extension of them.

The plan went off without a hitch. I called Gladys when I climbed onto the bus, and when the bus passed by her house she brought my bag to the curb which the ayudante carried up and tied to the roof of the bus. When we got to La Cuchilla, my stop where I would meet the private shuttle, he had already brought my bag down. I shivered as I waited near the highway. Silence. Sun peaking out from cloud blankets, I waited from 5:25-5:45am in complete silence, thinking every Pullman Bus was my shuttle until it left me in it’s windy wake, making me colder. I wrapped one article of clothing around my neck, a romper, but I was still cold. When the shuttle finally pulled over, I offered the driver Q200 if he had change (which he did not) or Q145. The driver said: “Oh but that extra Q5 is for my breakfast..” Well he didn’t have change, that’s his fault. When we stopped in Tecpán two hours later, I broke a 100 and furnished his Q150, cabal. This tour bus was not a comfortable one like the normal airport shuttle, it was a weird minivan. The driver was whistling through his teeth like he was pleasantly plotting a murder, and I sat in the seat behind him unpleasantly plotting his. No one else seemed bothered except me. I’m not used to men that big. He could hardly fit into his neck collar or the driver’s seat. I took in his profile while being perpetually perturbed by his stupid 6am whistle while everyone else slept, a mother and son to the my left.

My neck eventually accepted the discomfort of sleeping without a place for my head. I wrapped my romper tighter around my neck, held my arms together and bobbed into sleep between bumps and curves. We stopped in Guatemala City, at a place I did not recognize, and the tall driver who needed Q5 for breakfast passed two of us off to another driver. The man I was with took the front seat without asking or offering. We were just 2 now in a compact car with a stranger driver. This had never happened on the shuttle ride before, it always took me straight to the airport. When the guy in the front seat spoke to me in English thickly draped in a Spanish accent, I responded to him in Español. I did not want to entertain his English. But when he told me his story, he was actually fascinating. This man spoke German, Italian, English, Spanish (natively) and now, as he is working in Pana, he is learning Kaq’chikel. This I admire most. Because of the racism against Indigenous Peoples in Guatemala, many Spanish-speaking people have no interest in learning Mayan dialects. But his coworkers and staff speak it, he explains to me, so he is learning it. He tells me that Italian is his favorite language. I wouldn’t know enough of it to tell you if it was my favorite. I’m just grateful to be understood in any language these days.

The (second) driver removes my bag from his trunk and as he waits for his tip, I do not give him one. I do not even understand who he is or why I am in a random compact car. I walk into the airport and the check-in counter is littered with 50+ cargo-industrial bags. But it is too early to attempt a check-in, so I heave my bag up a cascade of steps and order my drink at “& Cafe.” “Can I ask you to froth the milk before you pull the espresso?” “Um sure?” they say. They don’t know about how espresso sits and gets a burnt flavor. But that’s how everyone in this country pulls shots of espresso: wrong. The very country where the coffee originated.

I sit and write a draft for the blog, my visit to the aldeas of San Juan. A young girl with braces, an unusual site in Santa Clara, asks if she can leave her phone on the table where I am sitting so that it can charge. She disappears. As I get up to leave after 1 hour of progress, she reappears to retrieve her phone. I lug my bag back down the stairs, wait in the check-in line, and heave it onto the weight counter. The check-in assistant does not ask me: “English or Spanish?” but assumes English and explains to me: “On Fridays there is a weight limit. You can see with the excess of bags here that if we surpass the weight limit, you will not be able to get on this flight.” I freeze. I think about pulling the Peace Corps card. I can’t spend the night in Guatemala City. What would I do? I look at him: “In that case what would happen with my bag?” as I watch it roll down the conveyor belt. “Oh if you stay, your bag stays.” I take my passport in my hand and begin to walk away, terrified, and he says: “I didn’t mean to scare you… I just wanted you to understand why you didn’t get on if you don’t get on.” And I looked at him and said: “Well I’m sufficiently scared” as if to say mission not accomplished. Who does he think he is? Talking to me in English in Guatemala… I am never prepared for that. Plus he was very tall. Weirdo.

After a touch-and-go wait at the gate, I am lucky enough to get a seat and say to the gate staff: “Feliz Navidad!” to their confusion. I call Clara with my remaining battery life and say: “ya estuvo, Clara! Me acceptaron, gracias a Dios.” And I am listening to the people in front of me, in matching, bright-colored mission trip t-shirts, concerned over their friends’ bags. Later I hear him say “Praise God” a blast from my past, and a preview of my visit home.

I try to filter out all the profiles of characters on this flight who are not like me. I feel like the only person like me. I find my seat, 24B, with a kid on my left and another kid on my right. Early 20s. I am in a middle seat and I am so happy to be in a seat at all.

How has this day already been 8 hours long and I am just buckling my seatbelt in 24B? Peace Corps. The seat has a USB outlet so I can charge my phone. Miracles after miracles. And what comes more to my surprise, I don’t actually hate the kid on my left. First we talk in Spanish until we both realize that we both speak English and English makes more sense. I can tell that he is young by his vernacular: “Sick” he says. What’s next? Lit, shook, ratchet? I watch a documentary on Martin Luther King as I color in my “Relájete” adult coloring book from Tanya. I just use blue, dark and light, to give life to this mandala. I talk to this kid like there are no stakes, myself a 32 year-old woman in Peace Corps and himself a baby-child from Nebraska in jorts, working for Delta. By the end of the flight, my hand is in his and I am equally befuddled but riding out whatever this odd attraction has delivered. He gives me his email, tells me he will be in Pana for his cousin’s quinceñera. I tell him I’ve never been to a Quince and I want to go. He tells me I should. He says he will be expecting and email from me tonight, we hug at customs and walk in different directions.

I get on the airport wi-fi to tell Emily I have landed. I breeze through customs and notice how unusually friendly the Atlanta Airport has become. Emily tells me she is waiting at the gate. I wonder if she has a stick for the bolos and the chuchos. Airport staff are greeting me and clicking a counter as I pass them. There is photography up on the walls by local artists. What is this strange land that I don’t recognize, but is my home? My bag arrives on the belt and I laugh at the baggage attendant. He touched something on a bag that was suspect and lifted his fingers to his nose, his face very displeased. I laughed and said: “Did something happen?” He said: “If it’s wet it’s suspect..” and we both laughed: an interaction my Pre-Peace Corps self wouldn’t have had. Emily is standing, bright as sunshine and without a bolo stick, at my finish line. We hug and I have stepped into my old self again. Just like that, I am not a foreigner. I don’t have to be explained. And I go unnoticed.

I get in Emily’s new car, a Subaru, but we talk like no time has passed. We cross the empty Atlanta highway, an automatic transmission with no gear shifts, no stops and starts to load passengers, I didn’t even have to hand her money for the ride or sign-in for the Peace Corps shuttle. Friday at 7:30pm. I request a stop at Publix to buy my sister a plant and bonus: two pints of Ben N Jerry’s CORE ice cream, 2 for $5. I should have bought 20 and brought them all to Santa Clara, if I lived in a world where states of matter didn’t change. Salted Caramel and Brownie Blast were the ultimate choices. We walked outside and I readjusted once again to the stubborn sauna air of Georgia and the fact that the sunshine is still inviolate nearing 8pm. In Guatemala, the sun is set at 6:30pm year-round. I forgot about the feeling of freedom that light provides after 6. I decide not to mention the joven who held my hand on the plane, as surprising and strange as it was, I will probably never see him again. Emily would have been 100% ready for me to girl-out, but a woman must pick her moments.

Emily graciously dropped me a block before Adrienne’s house, understanding that it most be a moment for me and Gretch, and I walked up the steps to Adrienne’s house, my finish line. As I set-up the camera on the floor, I knocked and waited for Chris to open the door. Immediately I heard Adrienne’s voice and tears, she hugged me as Ruby pitter-pattered at our feet. Dogs can be so happy about their owner returning home everyday, but I don’t know if dogs grasp my journey over three vehicles, a plane I nearly missed, passport, customs, and home. They just understand “she’s here again.” The cutest part about this surprise is that they are both wearing the bright yellow “30” shirts that Adrienne crafted for my 30th birthday. We laughed and ate ice cream as the surprise settled in around us and detail the steps of my decision: did I want to surprise Adrienne or not? Chris and I debated back and forth. Adrienne divulges that she had an inkling from overseeing a text. Adrienne is suspicious and officious, and Chris is not quite cagey enough to pull one over on her.

Being home was interesting, driving a car was interesting, wearing traje: empowering. But this trip wasn’t about being in the USA, it was about being with my family, wherever they were. I did make sure to keep a mental list of all of my favorite things I needed to eat/do, and to buy my host family bulk vitamins and an electric tea kettle at Costco.

But there was still to surprise my parents. After Chris, Gretch and I made a dent in our ice cream, I put my 30 shirt on too (of course I packed it and brought it home), we put Ruby in the back and I got in my sister’s new car. Chris and Adrienne call it “The Luxury Vehicle.” I’ll school them on luxury… We pull up to Mableton, GA, and I tell Adrienne to ask Dad to come out, “there is something heavy in the car that she needs help lifting.” It takes him a moment to register that it is me, sitting in the backseat under the car light, and he points at me and says: “You Dirty Dog!” confirming that I pulled it off, that he was surprised too. He laughs and says: “Come On In.” He calls my mom out of her room: “Someone is at the door” and she starts talking to me like she is expecting me and then says: “Is that my daughter?” and we all laugh and hug. The laughter ushers me into my home and distances me from my other home, my home in Santa Clara, empty.

We sit, sip a delicious red wine that my mom was introduced to in Panajachel of all places and sought out in the States, and I recount the tale of my 3:30am start from chucho sticks to the airport scare to my eventual arrival in Atlanta, my other city. We hug, take some photos and head back to Adrienne’s house. I sleep with Ruby at my side on a mattress as fluffy as my dreams. In the morning I ask Chris to take me to Dunkin’ Donuts drive-thru “America Runs on Dunkin” and buy both of us an Iced Caramel Macchiato. A homeless man has approached his car, asking for cash, and a Dunkin’ Donuts employee yells out at the man: “Ay! You can’t do that here.” I guess there’s no panhandling/soliciting posted somewhere in the parking lot?

He drops me back at home and Ruby and I go on a walk on the Atlanta Beltline, a 10 minute-walk from Adrienne’s house. I grip her tightly on the leash as she lashes out at other dogs if I’m not vigilant. I laugh to myself at the dog culture in the States that does not exist in developing countries. The chuchos suffer so much in Santa Clara, kids throw rocks at them, people kick them, cars skid into them and people tie them up with wire around their necks. No one, no one, picks up dog poop in plastic bags. It’s a hard life for the dogs. It’s a harder life for everyone in Santa Clara. Even the lowest income rung in Atlanta doesn’t hold a pathetic candle to the houses, healthcare, education and teeth of the Guatemalan poor.

But as much of a blessing as money is, it does not incite love between families or host moms that walk you to the bus. Money and luxury have isolated people in my country, not brought us closer. Love is born out of relying on one another, on empathy, and rare is the day in the USA that I feel vulnerable enough to even ask for directions from a stranger, much less a moment of their time or a hand.

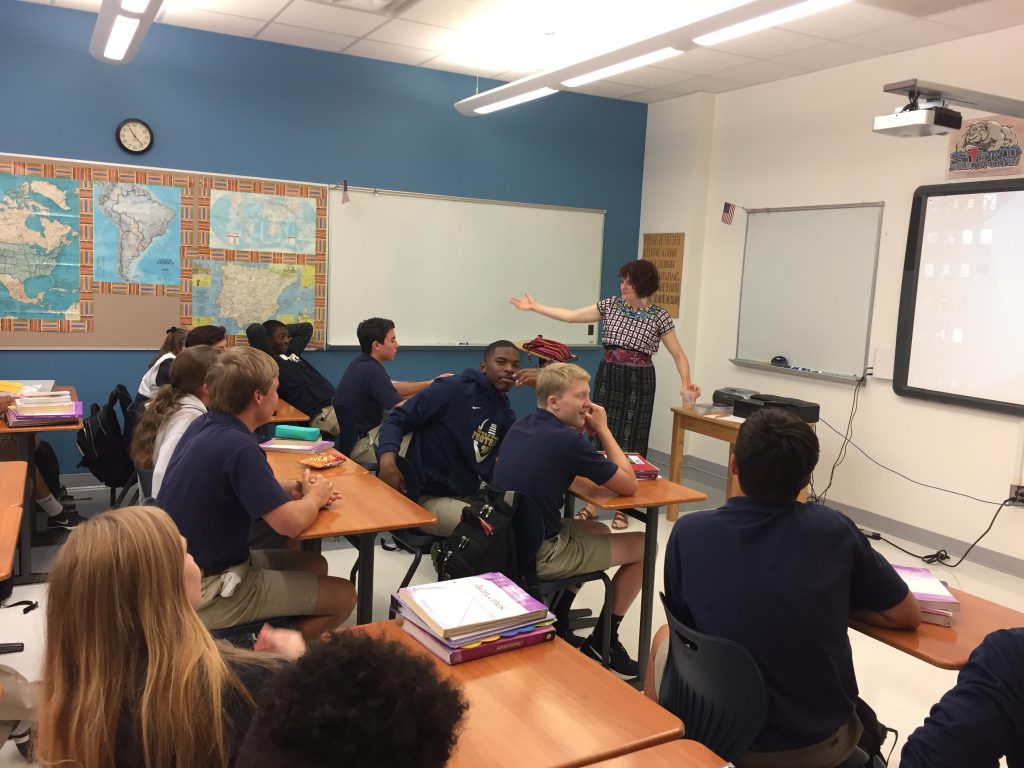

I manage to see all the friends I hope to, and doing two meetings for “Goal Three of Peace Corps: Teaching US Americans about Guatemala.” I am careful to say to each group that I am a foreigner in Guatemala, and I do not have the authority to explain it as if it is my country, my culture. But as an outsider, I can share my experience and perspective. I walked onto my old high school campus, the place of so many dreams where I flounced around in my school girl uniform, where my body image demons were born. But this time I was wearing a different uniform: the traje of Santa Clara, which I even figured how to put on myself. I woke up that morning and wrapped the woven belt around my waist.

When I went to visit Marguerite, my dear friend for half of my life, I got to see her grown-up house. It’s massive, 5 bedrooms and I can’t remember how many bathrooms. I helped her install her curtain rods, excited to have a power tool in my grasp after so many months. And like all of my friends with basements, she tells me: You can live here while you find your footing again. I think my friends with basements want me to live in the bowels of their homes because I have no home. I appreciate the sentiment, but now more than ever, I want to live above ground. I deserve just as much a place on land even if I’m not ‘established’ in the traditional sense.

After 4 days, Adrienne drops me at the airport. Saying goodbye is always hard. I think it is harder for Adrienne than anyone else in my world. But my lifestyle has made it unavoidable.

– – – – – – – –

When I returned I had two approved work days in the office. During these two days, I experienced the iPocalypse. My phone refused to charge or turn on. I panicked because my dad had just encouraged me to get a new phone while I was in the States. I said: “No. I’ll buy a new one with my readjustment allowance when I finish service.” Then the thing didn’t turn on the second I was on Guatemalan soil. Q250 later (roughly 35 bucks) my charging port was replaced and my phone provided mercurial functionality. Problem temporarily solved.

On Friday morning, I woke up early and headed home to Santa Clara. Actually, to be fair, I completely slept through the shuttle and missed it for the first time ever. I was anxious to give my suitcase to the ayudantes because I hear that bags get stolen on these routes, but I had no choice. Thankfully, the ayudantes dutifully subired and bajared my bag without it disappearing and when I made it to Km 148, I was home again: the gateway to my pueblo. In another 30 minutes of winding hills, green and gray clouds, I got off the bus and walked up to my home, waving at neighbors waving back at me, and greeted Abuelita, smiling and laughing, at the door. “Ya xat kulik?” You came back? “Gracias, gracias” she says, pats me ever so lightly on the arm and laughing. “Ya no ‘Buelita” I say to her. She laughs again.

When I opened my door upstairs I quickly unpacked my suitcase, thrilled by my peanut butter stockpile, while taking note of the glean of my tile floors. Clara mopped while I was gone. I think they think I don’t clean and that the apartment will go to ruin if they don’t intervene. Having said that, will I complain that someone else mopped? Not my favorite sport. I grabbed my teaching bag and went to school, arriving in just enough time and miraculously, my students had prepared their sessions to present. After truly an entire school year, we would make it through this unit Primeramente Dios.

The next week, my phone’s functionality a circus act, Clara flipped through my pictures of home before the battery died again. I showed her my traje that I wore around Atlanta and she was impressed that I could put it on by myself (necessity). She always helps me put it on when I am at home. I walk downstairs and say auxilio which means: “Aid!” She always laughs and suits me up. She swiped through myriad photos of Ruby, our walks, and our dinner at Fritti with my family of five. She paused on the photo of me driving my 2004 Pontiac Vibe and said: “Qué dichosa la Natalia..” Clara is 40 and has never driven a vehicle. She’ll never own a vehicle. They’re too expensive. She’ll never see the USA, they’ll likely deny her travel VISA like they have so many others.

And Clara’s right. I am dichosa, I am lucky. My parents bought me my first car at 16, my parents paid for my education, I have a passport and I speak the international language of business, English. I might be a volunteer but that was a choice, inherent in the word volunteer, but poverty is not a choice for the people of this pueblo where survival is a lifestyle. How many times can I remember and forget the reality of the world I live in?